《国家利益》:为何美国还没有学会赢得战争? [美国媒体]

从亚洲到中东,美国外交政策上的困难正在成倍增加。面对在阿富汗失败的前景,奥巴马总统在其军事顾问的建议下(翻转了先前的立场),宣布了一项新的、空洞的并且显然是开放性的“战略”,其中包括派遣更多的美军的选项。他承诺要“获得胜利”,但没有真正解释我们如何才能知道我们是否已经赢了。

Why America Hasn't Learned to Win Wars

为何美国还没有学会赢得战争?

AMERICA’S FOREIGN-POLICY difficulties are multiplying, from Asia to the Middle East. Faced with the prospect of losing in Afghanistan, the president on the recommendation of his military advisers (and reversing a previous stand) has announced a new, notably vague and apparently open-ended “strategy” that includes sending additional U.S. troops. And he promises to “win,” without really explaining how we will know if we have won.

从亚洲到中东,美国外交政策上的困难正在成倍增加。面对在阿富汗失败的前景,奥巴马总统在其军事顾问的建议下(翻转了先前的立场),宣布了一项新的、空洞的并且显然是开放性的“战略”,其中包括派遣更多的美军的选项。他承诺要“获得胜利”,但没有真正解释我们如何才能知道我们是否已经赢了。

In what has been called a “silent surge,” the administration is deepening American involvement in the endless conflicts raging across the Middle East and Africa. Relations with Russia have soured measurably, if not yet to the extent Trump’s hyperbolic rhetoric suggests. A full-fledged crisis with North Korea erupted in August and continues to smolder. And the president has even tossed about possible military intervention in Venezuela, an idea that anyone with even a scant knowledge of the history of U.S. relations with Latin America would not seriously entertain.

在所谓的“沉默的浪潮”中,奥巴马政府正在深化美国对中东和非洲地区无休止的冲突的介入。美国与俄罗斯的关系已经明显恶化,即便还没有达到特朗普夸张的言辞所暗示的程度。今年8月,朝鲜爆发了一场全面危机,而且危机的阴云仍在持续郁积。总统甚至还对是否在委内瑞拉进行可能的军事干预摇摆不定,而任何对美国与拉美关系历史稍有了解的人都不会认真考虑这个选项。

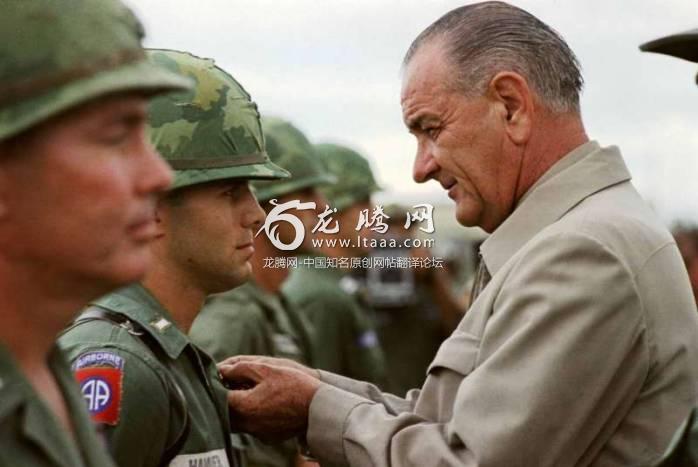

Coincidentally, we are “commemorating” the fiftieth anniversary of the Vietnam War, a conflict that dragged on for years and tore this nation apart. Throughout 2017, the New York Times online edition ran two articles a week on the war in 1967. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s television extravaganza aired in September, and a flood of new Vietnam-related books is hitting the market. Such significant anniversaries, particularly those involving national calamities, understandably invite reflection, in the hope that they may aid us in avoiding a repetition of the original error.

巧合的是,我们正在“纪念”越南战争五十周年,这场冲突持续了多年,并把这个国家撕成了碎片。整个2017年,纽约时报在线版每周都会刊登两篇关于1967年发生的这场战争的文章。Ken Burns和Lynn Novick的电视娱乐节目在9月播出,而大量与越南相关的书籍也在涌入市场。这样的重大纪念日,尤其是那些涉及国家灾难的纪念日,引发反思是可以理解的,人们希望这些反思能帮助我们不再重蹈覆辙。

Each historical situation is unique; to extract “lessons” from one to apply to another can be at best misleading, and at worst disastrous. The so-called Manchuria/Munich analogy that helped draw the United States into Vietnam is a prime example. Former Kennedy adviser James Thomson once proclaimed, in reductionist words—containing a large grain of truth—that the central lesson from Vietnam should be never again to “take on the job of trying to defeat a nationalist anti-colonial movement under indigenous communist control in former French Indochina,” a lesson, he quickly—and redundantly—added, that was of “less than universal relevance.” History can be a treacherous teacher. Still, an understanding of some of the things that went wrong in our once-longest war (Vietnam) might help us deal with its successor (Afghanistan) and the myriad other problems we now face.

每一个历史场景都是独一无二的;从一个历史场景中吸取“经验教训”应用于另一个历史场景,轻则有误导之嫌,重则引发灾难。推动了美国卷入越南战争进程的所谓的“满洲/慕尼黑”的类比就是一个很好的例子。前总统肯尼迪的顾问詹姆斯·汤姆森曾经用简化论者的措辞——其中包含了大量的真相——声称,从越南吸取的最重要的教训应该是再也不要“承担击败一个处于前法属印度支那的本土共产主义者控制之下的民族主义反殖民主义运动的任务”,他接着又画蛇添足地补充称,这个教训“是没有多少普遍意义的”。历史可以是一个奸诈的老师。尽管如此,对我们曾经经历过的最漫长的战争(越南战争)的一些错误行为的理解也许可以帮助我们处理后续的战争(阿富汗战争)和我们现在所面临的无数其他问题。

FROM EISENHOWER through Nixon, each new administration, certain that it was smarter and tougher, took power believing it could succeed in Vietnam where its predecessors had failed. We call this the certitude of the new guys. “We will not make the same old mistakes,” Henry Kissinger confidently announced upon taking office. “We will make our own.” In fact, like those who came before, the Nixon administration did make the same old mistakes—as well as plenty of new ones.

从艾森豪威尔到尼克松,每一个新政府都坚信自己是更聪明、更强硬的,相信在越南这个它的前任失败的地方自己会取得胜利。我们称之为“新来者”的确信。“我们不会犯同样的错误”,亨利·基辛格在就职时信心十足地宣布。“我们将创造我们自己的时代”。事实上,就像之前的那几届政府那般,尼克松政府也犯了同样的错误——就像之后的许多新政府一样。

Trump personifies, and takes to another level, this new-guy mentality. He constantly bemoans the problems he inherited from the alleged failures of those incompetents who preceded him while, often with bombastic language, he promises to solve the problems they couldn’t.

特朗普代表了这种新来者的心理,并把它提升到了另一个层次。他不断地为自己从那些在他之前的无能者的失败中所继承的问题而哀叹,而他常常用夸张的语言承诺解决他们所不能解决的问题。

It’s a little late for this one, perhaps, except that new guys continue to go through the revolving door that is the Trump White House. These newbies, and the president himself, no matter how smart and tough they think themselves, would do well to approach the problems they confront with humility and caution, especially those, like the president, who are totally lacking in foreign-policy experience and expertise. To be sure, they should learn from their predecessors’ mistakes, but they should keep in mind that they will make their own as well.

这可能有点为时已晚,也许是这样的,除非那些新来着继续穿过旋转门,否则它就是特朗普这届政府的事情了。这些新来者,以及总统本人——无论他们认为自己有多聪明、多坚韧——最好能以谦逊和谨慎的态度来处理他们面对的问题,尤其是像总统这样的人,他们完全缺乏外交政策经验和专业知识。可以肯定的是,他们应该从前辈的错误中吸取教训,但他们应该记住,他们也会做出自己的错误决定。

Another lesson from Vietnam so obvious as to be self-evident—easy in, not-so-easy out—has been ignored by perennially hubristic Americans from James Madison to George W. Bush. No one has stated it better than Lyndon B. Johnson, a year before he plunged into the quagmire by drastically increasing the number of U.S. combat troops in Vietnam. “It’s damn easy to get into a war,” LBJ told National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy prophetically in May 1964, “but it’s going to be awful hard to ever extricate yourself if you get in.”

另一个来自越南的教训则是非常显而易见的,以至于到了不言自明的地步:卷入战争是一件简单的事情,但是要从战争中全身而出却很困难——这一教训被自詹姆斯·麦迪逊到乔治·W. 布什以来所有傲慢自大的美国人都忽视了。没有人能比林登·B. 约翰逊更加清楚地阐明这一点。在他陷入困境之前一年,他大幅增加了美国驻越南作战部队的数量。“卷入一场战争很容易,”林登·约翰逊在1964年5月对国家安全顾问麦克乔治邦迪如是说道,“但是如果你陷进去的话,要想让自己从中逃脱是非常困难的”。

Given how frequently neoconservatives quote Winston Churchill in so many other contexts, it is striking that they don’t take to heart this particular admonition of his: “The Statesman who yields to war fever must realise that once the signal is given, he is no longer the master of policy but the slave of unforeseeable and uncontrollable events.” Former president Barack Obama took a lot of flak for winding down the U.S. military presence in Iraq in 2010. But given how hard it is to disengage from a major military commitment, the fact that he was able to do so at all is remarkable. The lingering U.S. commitment to Afghanistan, which President Trump now proposes to increase again, is more typical of the general pattern of easy in, not-so-easy out for major military commitments, even ones that are clearly not going to end well no matter how long we stay the course.

有鉴于新保守主义者在其他如此多的情况下频繁引用温斯顿·丘吉尔的名言,令人震惊的是他们并不认真关注他所发出的这个警告:“屈服于战争狂热的政治家必须意识到,一旦给出了信号,他就不再是政策的主导者,而只是不可预见的和无法控制的事件的奴隶”。美国前总统奥巴马在2010年结束了美国在伊拉克的军事部署,他因此遭到了很多的谴责。但是考虑到摆脱一项重要的军事义务的束缚有多么困难,他能够做到这一点真的是一件了不起的事情。美国对阿富汗不断延长的义务——现在特朗普提出再次延长——则是重要军事义务的“易进难出”普遍模式的更典型写照,即便是对于那些显然不会得到善终的义务而言也是如此——不管我们在这一进程中花了多少时间。

A THIRD lesson might be called the impotence of idle threats. Inasmuch as Richard Nixon had a “secret plan” for peace, as he claimed during the 1968 campaign, it was based on the so-called “madman theory,” a stratagem of persuading an enemy of one’s irrationality and then threatening the use of nuclear weapons to force a settlement. “They’ll believe any threat of force Nixon makes because it’s Nixon,” the candidate confidently told aide Bob Haldeman while strolling on the beach.

第三个教训可以被称为闲置威胁的无效性。正如理查德·尼克松在1968年的竞选中所宣称的那样,他的“秘密计划”是建立在所谓的“疯子理论”的基础上的,这是一种让敌人信服某人的不理性,继而通过威胁使用核武器来强制达成和解的策略。“他们会相信尼克松的任何威胁,因为他可是尼克松”,这位候选人在沙滩上漫步时自信地告诉Bob Haldeman。

“We’ll just slip the word to them that, ‘for God’s sake, you know Nixon’s obsessed about Communism . . . and he has his hand on the nuclear button’—and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace.”

“我们只是跟他们说:‘看在上帝的份上,你知道尼克松对共产主义的痴迷的……他把手放在了核按钮上’,于是胡志明本人也将于两天内来到巴黎祈求和平。”

Nixon’s madman approach drew upon the mistaken belief, an article of faith among some Republicans, that Eisenhower had forced the Chinese to settle in Korea in 1953 by making nuclear threats. It also derived from academic studies of “diplomatic blackmail” developed by the economist Thomas Schelling and, ironically, by Nixon’s future nemesis, Daniel Ellsberg.

尼克松的疯子式的做法是在利用一些共和党人的错误信念,即艾森豪威尔已经在1953年通过发出核威胁而迫使中国人和解。这也源于经济学家托马斯·谢林所发展的“外交勒索”的学术研究,讽刺的是,尼克松后来的死对头就是托马斯·谢林。

Nixon’s madman diplomacy failed. Through various sources, he warned Hanoi in the summer and fall of 1969 that if a settlement were not reached by November 1 he would resort to “measures of great consequence and force.” His threats were singularly ill timed. Ho Chi Minh died in September, and the hard-liners who had long since supplanted him were not about to dishonor his cause by giving in to the United States. Those Nixon officials tasked to devise a military program to coerce North Vietnam concluded that nothing was likely to work, and that drastic escalation would bear a high domestic political cost.

尼克松的疯子外交终告失败。他在1969年夏天和秋天通过各种渠道警告河内,如果在11月1日之前未能达成协议,他将采取“会造成严重后果的武力措施”。他的威胁非常地不适时。胡志明于9月去世,而那些早已取代他的强硬派则不会通过屈服于美国而使他的事业蒙羞。那些负责制定出一个军事计划来迫使北越让步的尼克松官员得出结论说,没有什么是可行的,而且事态的急剧升级将会使美国国内的政治局势进一步恶化。

It would be natural for anyone assuming the American presidency to be awed by our military power. It is human nature to believe that small nations, even ones with nuclear weapons, can be easily cowed by Mr. Big. In fact, as various presidents have discovered, there are numerous powerful internal and external constraints on the use of the nation’s vast power. And hard experience should have taught us by now that other nations and peoples, however small and seemingly weak, are not easily intimidated.

对于任何一个认为美国总统对我们的军事力量充满敬畏的人来说,这是很正常的。相信小国家——即使是拥有核武器的小国——很容易被大国吓倒,这也是人性使然。事实上,正如许多总统所发现的那样,在使用这个国家的巨大力量时,存在着许多强有力的内部和外部制约因素。而艰难的历程本应该告诉我们:其他国家和人民——无论它们是多么弱小——都不会被轻易吓倒的。

Another cautionary “lesson” from Vietnam is to resist the temptation of quick-fix strategies—in football lingo, the Hail Mary pass. In the run-up to massive U.S. involvement in Vietnam, decisionmakers like Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton, already doubtful that military intervention would compel North Vietnam to stop aiding its southern allies, sought a Hail Mary pass in the theories of coercive bombing developed by Schelling, his friend and former Harvard colleague. In late 1964, working with the State Department, McNaughton devised a bombing campaign of graduated pressures against North Vietnam that he hoped would achieve U.S. goals and avert a disaster in Vietnam. “What we need is a theory that will limit our role,” he confided to his diary.

来自越南战争的另一个警示性的“教训”是:要抵制任何应急战略的诱惑——用橄榄球术语来说就是万福玛利亚传球。在美国大规模卷入越南战争之前,像助理国防部长约翰·麦克诺顿这样的决策者已经对通过军事干预迫使北越停止援助其南部盟友的效果怀疑,他开始寻求谢林——他的朋友和之前在哈佛大学的同事——所发展出的强制轰炸理论中的万福玛丽亚传球策略。1964年底,通过与美国国务院的合作,麦克诺顿设计了一场针对北越的压力升级轰炸行动,他希望能籍此实现美国的目标,避免一场发生于越南的灾难。“我们需要的是一个限制我们所扮演的角色的理论,”他在日记中如此写道。

Schelling’s model and the Rolling Thunder air campaign that drew upon it erroneously assumed the same cost/benefit calculations on both sides. In fact, the United States sought merely to demonstrate its resolve to allies and enemies; North Vietnam sought to liberate what it considered its homeland. Rolling Thunder evolved into a prolonged, vastly destructive and ultimately futile exercise in coercion.

谢林的模型和源于这一模型的雷霆空中行动都错误地认为双方承担了同样的成本和收益。事实上,美国只是想向盟友和敌人展示其决心;北越则试图解放它眼中的家园。“雷霆行动”演变成了一次漫长的、极具毁灭性的、最终却徒劳无功的强制行动。

The Trump administration, similarly, faces a set of bad choices in Afghanistan. Setting aside his own well-founded instincts against escalation, the president was persuaded by his top advisers that a hasty withdrawal would create a vacuum for terrorists such as ISIS and Al Qaeda. Like McNaughton, and Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, he succumbed to the lure of the quick fix in the graveyard of empires. Hail Mary passes rarely win football games. Why should we expect them to win wars?

同样的,特朗普政府在阿富汗也面临着一系列糟糕的选择。奥巴马的高级顾问们相信,仓促撤军将为“伊斯兰国”和基地组织等恐怖分子制造一个真空环境。就像麦克诺顿和特朗普的前任巴拉克·奥巴马一样,他也屈服于在帝国墓地中实施权宜之计的诱惑。万福玛丽亚传球策略很少能赢得足球比赛。为什么我们要期待他们能赢得战争?

IN VIETNAM, both U.S. president Lyndon Johnson and his North Vietnamese counterpart, party general secretary Le Duan, repeatedly miscalculated how each would respond to the other’s initiatives. In escalating the war in 1965, Johnson and his advisers assumed—incorrectly—that North Vietnam would acquiesce to an independent South Vietnam rather than risk destruction at the hands of America’s vast military power. In 1964, and again in 1968 and 1972, the aggressive—and reckless—Le Duan assumed that he could win in South Vietnam by drastically escalating the war. In each case he failed, and in so doing he imposed horrendous costs on his people and nation.

在越南,美国总统林登·约翰逊和北越主席黎笋不断地对相互之间的反应做出了错误估计。在1965年的战争中,约翰逊和他的顾问们都认为,北越将默许南越独立,而不是在美国庞大的军事力量的威胁下实施破坏活动。1964年——还有之后的1968年和1972年,带有侵略性和鲁莽的黎笋认为他可以通过大幅升级战争赢得南越。在各种情况下,他都失败了,他的所作所为给他的人民和国家造成了巨大的损失。

Miscalculation lies at the root of many, if not most, foreign-policy crises and wars. Trump and his advisers should be very careful about what they say and do, and especially about what they assume about the possible behavior of enemies both real and potential. War and peace is not a schoolyard game of one-upmanship. It is, literally, life and death.

错误的估计是许多外交政策危机和战争的根源——即便不是最主要的源头。特朗普和他的顾问们应该谨言慎行,特别是在关于他们对潜在的敌人可能实施的行为的假设方面。战争与和平不是一场运动场中的比赛,实际上,它关乎生与死。

IN VIETNAM, too, we became entangled in what one top official (with no apparent sense of the paradox) called an “all-out limited war” through a series of decisions made over almost two decades. With each step out on the slippery slope, from aid to advisers to more advisers to combat troops, we became more deeply committed until that commitment itself—our credibility—became the essential reason for further, massive escalation.

在越南也是如此,在20年的时间里,通过一系列的决策,我们卷入了一场一名高级官员所谓的“全面的有限战争”(其中并没有明显的矛盾感)。从援助到顾问,再到更多的顾问,再到作战部队,我们每一个步子都迈得更大,我们越来越深陷其中,直到义务本身——我们的信用——成为了战争进一步升级的关键原因。

The dangers of incrementalism certainly apply today in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, where our commitment is limited to advisers whose numbers and roles may soon be expanded. How, after sixteen years, can we continue to believe that a small—or even a large—infusion of U.S. troops in Afghanistan can do what more than one hundred thousand could not previously accomplish? At what point do we decide that even a major commitment of Americans cannot compensate for the weakness of our ally?

渐进主义的危险如今在阿富汗和伊拉克等地也同样适用,我们的义务仅限于派遣顾问,他们的人数和所扮演角色可能很快就会扩大。在16年之后,我们怎么能继续相信美国在阿富汗的一支小部队——甚至是一支大规模部队——能够完成之前超过10万的军队都无法完成的任务呢?在什么时候,我们认为即使是美国人的重要军事义务也无法弥补我们盟友的孱弱呢?

Of course, with Trump, as with Barack Obama and George W. Bush, domestic politics likely influenced decisions to up the ante in Afghanistan. No one wants to see that country “lost” on his watch. This is eerily reminiscent of what Ellsberg called the “stalemate machine” in Vietnam, with each president doing just enough to keep South Vietnam afloat until he leaves office.

当然,就像奥巴马和乔治·W. 布什一样,特朗普的国内政治可能会影响到他在阿富汗所下的赌注。没有人希望看到这个国家在他的手表上“迷失”。这让人想起了埃尔斯伯格所谓的越南战争中的“僵局机器”,每一个总统在其任期内都做了足够的事情,让南越政权在他离任之前能够维持下去。

CLOSELY RELATED is a geopolitical truth that Americans historically have been loath to accept—that power, no matter how great, has limits. In the 1960s, the United States was the world’s greatest power militarily and economically, but in Vietnam it could never find ways to use that power to attain its political goals of thwarting North Vietnamese expansion and building, from scratch, a Jeffersonian democracy in the South.

与此密切相关的是一个美国人历来不愿接受的地缘政治真相——无论多么伟大的强国都有其力量的限度。在上世纪60年代,美国在军事和经济层面上是世界上最强大的国家,但在越南,它永远无法找到利用这种力量实现其政治目标的方法,即挫败北越的扩张,并从零开始建立一个杰弗逊式的民主国家。

We still enjoy a vast advantage over other nations in military spending and hardware. No more than in the Vietnam era does that mean we can solve the problems we face on terms we favor. Our power greatly exceeds our capacity to use it.

在军事开支和硬件方面,我们仍然享有凌驾于其他国家之上的巨大优势。就像越战时期一样,这意味着我们可以用自己喜欢的方式来解决我们面临的问题。我们的力量大大超过了我们使用它的能力。

Americans tend to believe that what they do—or don’t do—is the key to success or failure in foreign policy. In fact, as Vietnam showed so clearly, local circumstances often determine outcomes.

美国人倾向于相信他们做与不做是外交政策成败的关键。事实上,正如越南所表现的那样,当地环境往往决定了结果。

A weak, divided South Vietnam proved so unreliable as an ally that after 1965 we tried to do the job of defeating the North almost on our own. At the same time, our resolute, utterly committed foes, the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) and North Vietnam, were the ones in fact willing, in JFK’s words, to “pay any price, bear any burden” in pursuit of victory. They had sanctuaries to protect themselves from extermination, and allies like China and the Soviet Union to provide massive assistance.

一个软弱的、分裂的南越被证明是不可靠的盟友,在1965年之后,我们试图用自己的办法打败北越。与此同时,我们的决绝的敌人——越南南方民族解放阵线和北越——用肯尼迪的话说——实际上是愿意“付出任何代价,承受任何负担”来追求胜利的。他们有保护自己免遭灭绝的庇护所,还有像中国和苏联这样的盟友为它提供大量的援助。

In Afghanistan today, we back a weak, corrupt central government in a vast nation with no tradition of federal control and a small scattered population divided along ethnic, religious and tribal lines, surrounded by nations with more compelling interests and greater ability than the United States to affect the outcome—while fighting against a resilient foe that seems magically to recreate itself after each setback, enjoys sanctuaries in Pakistan that help it to do so and possesses infinite patience. Can the application of our power make up for these intrinsic disadvantages?

在今天的阿富汗,我们又碰到了一个弱小、腐败的中央政府,它统治着一个广袤的国家,但是这个国家却没有联邦控制的传统,有的只是被民族、宗教和部落控制线分割得支离破碎的人口,而且包围着它的是一些拥有比美国更多的驱动力和力量去影响结果的国家——同时在这里美国还要对抗一个顽强的敌人,它在每次被挫折后都能神奇地回复自己的力量,拥有位于巴基斯坦的庇护所——这可以帮助它做到这一点,还拥有无限的耐心。我们的力量运用能弥补这些内在的不足吗?

Both then and now, American leaders have failed to know their enemies. LBJ longed to get “ol’ Ho” Chi Minh in a room where he could employ his formidable powers of persuasion, in the mistaken belief that Ho was no different from the labor leaders and legislators he was accustomed to manipulating. Ho was not a senator or labor leader, of course, and even if LBJ had gotten him in a room, he likely could not have persuaded him to compromise on American terms.

无论是过去还是现在,美国领导人都没有了解他们的敌人。林登·约翰逊渴望在一间能运用他强大的说服力的房间里制服胡志明,他错误地认为胡志明与他习惯操控的劳工领袖和立法者没有什么不同。当然,他不是参议员或劳工领袖,即使约翰逊把他送进了房间,他也不可能说服他按照美国的条款妥协。

Most alarming is that U.S. leaders apparently had no idea that after 1963 at the latest, Ho did not wield dominant power in Hanoi. In fact, the pragmatic Ho’s earlier compromises with the French in 1946 and at the Geneva Conference in 1954—his “two mistakes”—had become by 1965 for Le Duan and his hawkish allies a compelling mantra against any compromise with the United States that in any way undermined the fundamental goal of a unified Vietnam under Hanoi’s control.

最让人担忧的是,美国领导人显然不知道1963年之后,胡志明在河内并没有发挥主导作用。事实上,务实的胡志明在1946年与法国和1954年在日内瓦会议上所作出的早期妥协——他所犯下的“两个错误”——至1965年对于黎笋和他的鹰派联盟而言已经成为一个强力的咒语,它反对与不惜一切手段破坏在河内控制之下实现越南统一的基础目标的美国进行任何妥协。

In dealing with our Middle East adversaries—and China, Russia and especially North Korea—President Trump ought not to assume that they will respond to his bluster and blandishments in the same way partners and rivals in the business world did. Rather, the art-of-the-dealer in chief needs to recognize that other countries have their own history and perspectives on the contemporary world that may, or more likely may not, accord with his, and that getting to “yes” with them may require very different tactics than those he used to build his real-estate empire.

在与我们的中东地区对手——以及中国、俄罗斯,尤其是朝鲜打交道时,特朗普总统不要以为它们会像商业世界的合作伙伴和竞争对手那样,对他的咆哮和奉承做出回应。交易者的技艺尤其需要认识到,对于当代世界而言,其他国家有着它们自己的历史和观点,它们也许——更有可能不会——与他的观点保持一致,而和它们和谐相处可能需要与他构建自己的不动产帝国截然不同的策略。

The admonitions recounted here undoubtedly appear weighted on the side of nonintervention or limited intervention. But these lessons are bipartisan. They are grounded in important premises of both conservative (prudence) and liberal (humility) political thought. Given America’s dismal record in the past few decades, such restraint appears prudent—and greater national humility about our role in the world appears eminently justified.

毫无疑问,这里的警告无疑增加了不干涉或有限干涉一方的权重。但这些经验是两党共有的。它们是基于保守(审慎)和自由(谦逊)的政治思想的重要前提而出现的。有鉴于美国在过去几十年里的惨淡记录,这种克制似乎显得有些保守,而对于我们在世界上所扮演的角色来说,更大程度上的国家谦逊态度似乎是完全合理的。

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10