中国文化是和平的吗? [美国媒体]

quora网友:中国文化是“文明型”的。任何一个中国人都会告诉你,中国有六千多年的历史。在历史的大部分时间里,中国是-- 或者至少被认为是-- 一个被野蛮人包围的文明国家。这一事实可以从它的名字“中国”中看出,这个词经常被翻译成“中央王国”,但我认为“中心国家”更为正确,就像……世界的中心......

Is Chinese culture peaceful?

中国文化是和平的吗?

Ronald Kimmons, fluent in Mandarin, BA in Chinese, former missionary to Taiwan.

罗纳德·基蒙斯,普通话流利,中文学士,前赴台湾传教士。

Chinese culture is civilized.

As any Chinese person will tell you, China has like 6,000 years of history.

For much of that history, China was - or at least perceived itself to be - a civilized nation surrounded by barbarians. This fact can be seen in its name - Zhongguo. This is often translated as “Middle Kingdom”, but I think it is more correct to say “Central State”. As in…the center of the world.

Being the most populous nation in the world is not a new thing for China. It has rivaled India for that title for centuries.

Chinese agriculture goes back as far as agriculture goes. And an agricultural society is a civilized society pretty much by definition.

There was a time in which China was without a doubt the wealthiest and most powerful country in the world. During this period, China sent out many exploratory seafaring missions, but it did not engage in any colonization, largely because it had no reason for doing so. China already had what it wanted.

Being a civilized culture, China values stability. Chinese culture teaches everyone to fulfill their proper role in society, avoid unnecessary risks, and not make a mess of things.

This, of course, means that China values peace.

However, if you think this means that there is something particularly pacifist about China, you are wrong. China’s culture is not a warmongering culture, but it is most definitely a culture with a long history of war. There were various periods in which the wars of Europe paled in comparison to the wars of China, both in scale and in savagery.

More importantly, though, China has a long history of leaders using the threat of violence as an important part of diplomacy. War is simply diplomacy by other means, and vice versa. China understands this as much as anyone.

China literally wrote the textbook on war.

So in short, China is peaceful in that it values civility and stability. But do not mistake the value it places on peace for pacifism. That is not it. Not at all.

Don’t poke the dragon.

中国文化是“文明型”的。

任何一个中国人都会告诉你,中国有六千多年的历史。

在历史的大部分时间里,中国是-- 或者至少被认为是-- 一个被野蛮人包围的文明国家。

这一事实可以从它的名字“中国”中看出,这个词经常被翻译成“中央王国”,但我认为“中心国家”更为正确,就像……世界的中心。

对于中国来说,成为世界上人口最多的国家并不是什么新鲜事。几个世纪以来,它一直在与印度竞争这个头衔。

中国农业可以追溯到农业发展的初期,从定义上来说,如果一个国家是一个农业社会,那它基本上也是一个文明社会。

曾经有一段时间,中国无疑是世界上最富有、最强大的国家。在此期间,中国派出了许多考察航海特派团,但没有进行任何殖民活动,主要是因为中国没有理由这样做。中国已经得到了它想要的东西。

作为一种“文明”型的文化,中国重视稳定。中国文化教导每个人要履行他们在社会中应有的角色,避免不必要的风险,不要把事情搞得一团糟。

显然,这意味着中国重视和平。

然而,如果你认为这意味着中国有某种特别和平主义的东西,那你就错了。

中国的文化不是一种好战的文化,但它绝对是一种有着悠久战争史的文化。

在历史的各个时期,欧洲的战争无论在规模上还是在暴力程度上,与中国的战争相比都相形见绌。

更重要的是,中国有着悠久的领导人使用暴力威胁作为其外交手段重要组成部分的历史。

战争只是通过其他手段进行的外交,反之亦然。中国和其他国家一样理解这一点。

中国确实写了一本关于战争的教科书。

《 战争的艺术 》(直译,其实就是《孙子兵法》)

因此,简而言之,中国是和平的,因为它重视文明和稳定。

但不要把它对和平的价值误认为是和平主义。

不是这样的,一点也不。

别惹那条龙。

———————————————————

Philip Lee, Guy in Hong Kong

Chinese culture isn’t just peaceful, it’s downright nerdy.

China, like all settled agricultural civilizations, has always tended towards a relatively peaceful culture. China is in no way unique in this respect. The same could be said for civilizations like Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley.

Farmers simply don’t benefit from war. They gain very little from victory, lose everything in defeat, and suffer heavily either way. Just the very act of going to war is bad for them because it means leaving their farms.

中国文化不仅是和平的,更是彻头彻尾的书呆子。

中国同所有定居农业文明一样,始终倾向于相对和平的文化。在这方面,中国绝不是独一无二的。埃及、美索不达米亚和印度河流域等文明也是如此。

农民根本不能从战争中获益,他们从胜利中得到的好处很少,如果失败就会失去了一切,无论哪种方式都会遭受巨大的痛苦。战争对他们来说是坏事,因为这意味着离开他们的农场。

What made pre-modern China unique was that it was the only civilization where the secular scholar, not the priest, and not the soldier was the first man of the state.

European civilization has always held the warrior as the first man of the state. Nobility in Europe was defined by martial prowess, a man gained the respect of his peers by being particularly good at killing his peers. This tradition seems native to all European civilizations starting with the Greeks themselves whose philosophers were also soldiers. The Romans spread their culture of martial alpha male dominance to all parts of the Mediterranean. The Germanic tribes that inherited the Western Roman Empire created the medi system of warrior nobility.

使得前现代中国独树一帜的是,它是唯一一个将世俗学者,而不是牧师或战士,当成国家第一人的文明。

欧洲文明一直认为战士是国家的第一人。欧洲的贵族是以武力为特征的,一个人特别擅长杀害他的同龄人,因而赢得了同龄人的尊重,这一传统似乎起源于欧洲文明本土,首先是希腊人,他们的哲学家也是士兵,罗马人把他们的军事头领统治文化传播到地中海的各个角落,继承了西罗马帝国的日耳曼部落创造了中世纪的武士贵族制度。

Civilizations in the Middle East has often been more religiously focused, making the priests the most important members of society, often its rulers, certainly the most respected. Both Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations were ruled by priest kings. Later the Hebrew tradition inherited the idea of making priests the ultimate authority figures. Islam carried on this by making the Caliph the head of both mosque and state.

It was only in China that the best way for a man to gain the respect of his fellow men was to become a total nerd. And people wonder why Chinese and other Chinese influence cultures today are so focused on scholastic excellence.

中东的文明往往更加注重宗教,使神父成为社会中最重要的成员,往往是其统治者,当然也是最受尊重的人。埃及文明和美索不达米亚文明都由祭司国王统治。后来,希伯来传统继承了使祭司成为最终权威人物的思想,伊斯兰教继续这样做,使哈里发成为清真寺和国家的首脑。

只有在中国,一个人获得同胞尊重的最好方法就是成为一个十足的书呆子。

人们不禁想知道为什么中国和其他受中国影响的文化在今天如此专注于学术上的卓越。

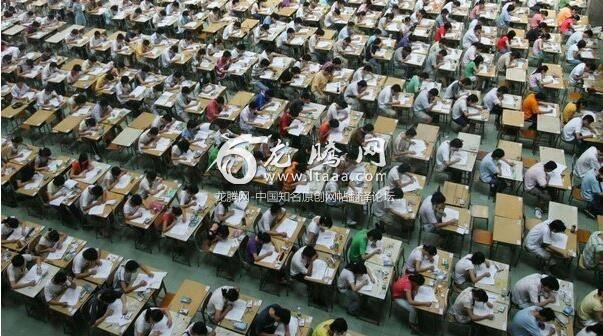

This is how you become the cool kid in school in China

这是如何成为中国学校里的“酷”孩子的方式。

This is how you become the cool kid in the Western world

这是成为西方世界“酷”孩子的方式。

———————————————————

Robert Maxwell

罗伯特 · 麦克斯韦尔

TL;DR - It’s a fool’s errand to ascribe basic attributes - such as fundamentally peaceful, fundamentally warlike, fundamentally tolerant, fundamentally intolerant - to a culture, since cultures are not monolithic things - Chinese included. China, like any culture, has militaristic facets that arose out of specific historical experiences, personal and collective - but while that does not make it superlatively peaceful, neither does it make it any more warlike than other cultures.

Not any more or less than most other cultures.

The question itself is difficult to answer because uating a singular culture in terms of “peaceful” or “warlike” is at best quixotic - cultures change and shift and our perceptions of them (whether we are foreign or not) are similarly in flux.

长文预警——

把基本的属性--比如基本的和平、好战、宽容、偏狭---归因于一种文化,这是愚蠢的。因为文化不是一成不变的东西---包括中国人,与任何文化一样,中国也有源自个人和集体特定历史经验的军国主义色彩---但这并不会让它变得超级和平,也不会让它比其他文化更好战。

与大多数其他文化一样,不会多也不会少。

这个问题本身很难回答,因为用“和平”或“好战”来评价一种独特的文化是不切实际的----文化不断变化和发展,以及我们对它们的看法 ( 不管我们是不是外国人 ) 也同样在变化。

It was not uncommon in the late 19th century and early 20th century to regard German culture as the most refined and humanistic culture in Europe - the birthplace of Thomas Mann, Goethe, Schiller. That perception (at least in the popular mind) certainly changed after WWII and even WWI and the Germans gained a reputation for having a “warlike culture,” almost entirely in retrospect and due to the contextual lens through which people saw them.

Similarly, it’s almost impossible to say whether or not a 4,000 (plus!) year old culture such as Chinese culture is inherently peaceful or inherently warlike. Most likely, it’s none of those things - all major cultures discuss, celebrate, and value warlike things (glorious battles, victorious generals) as much as they do issues of peace (great statesmen, golden ages of prosperity).

The expected answer is, no doubt, that China is the most peaceful nation to ever have existed on the face of the Earth. But, really, that’s not true, though it’s beyond the scope of the question, which has to do with culture. And I’m sure that some other answers are going to claim that China is definitely absolutely peaceful because (supposedly) they have not in their recent 60 years of existence begun a war, whereas America has. So, no doubt that response will go, China is peaceful and America is warlike, meanwhile all too simplistically asserting that it’s a cultural issue and not one to do with the multitude of economic, political, and situational variables that China and the United States do not share.

在19世纪末和20世纪初,把德国文化视为欧洲最精致、最人性化的文化---德国是托马斯·曼、歌德、席勒的诞生之地,并不罕见。这种看法( 至少在大众心目中是这样 ) 在第二次世界大战、甚至第一次世界大战后肯定发生了变化,德国人以拥有“好战的文化”而闻名,这几乎完全是回顾过去,也是因为人们从历史的角度看待他们。

同样,几乎不可能说中国文化这样的有四千年多年历史的文化是与生俱来的和平还是天生的好战。

最有可能的是,两者都不是——所有的主要文化对待和平问题( 伟大的政治家、繁荣的黄金时代 ) 和讨论、庆祝和珍视类似战争的东西 ( 光荣的战斗、胜利的将军 ) 程度上是一样。

毫无疑问,人们所期望的答案是,中国是地球上有史以来最和平的国家。

但是,实际上,尽管这与文化有关,却不是真的,这超出了问题的范围,我相信会有其它一些答案声称中国绝对是和平的,因为( 据推测 ) 他们在最近60年的中并没有发动过战争,而美国却发动了战争,因此,毫无疑问,这种反应会继续下去,但这是一个文化问题,而不是一个与中美两国不共有的众多经济、政治和局势变量有关的问题,中国是和平的,美国是好战的,这样的断言过于简单化。

So, is China peaceful, culturally? It’s impossible to say. But we certainly can say that Chinese culture has martial themes that are constantly repeated and explored and that it has militaristic facets.

Why is that? Let’s explore.

The four most beloved vernacular novels in Chinese literature are the so-called Four Great Novels (四大名着). They are:

The Water Margin (水浒传)

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义)

The Journey to the West (西游记)

The Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦)

那么,中国究竟是不是和平的文化呢?很难说。

但是,我们可以肯定地说,中国文化有不断重复和探索的军事主题,而且有军国主义的一面。

为什么这么说呢?我们来探索一下。

中国文学中最受欢迎的四部白话小说是所谓的“四大小说”(四大名着),它们是:

《 水浒传 》

《 三国演义 》

《 西游记 》

《 红楼梦 》

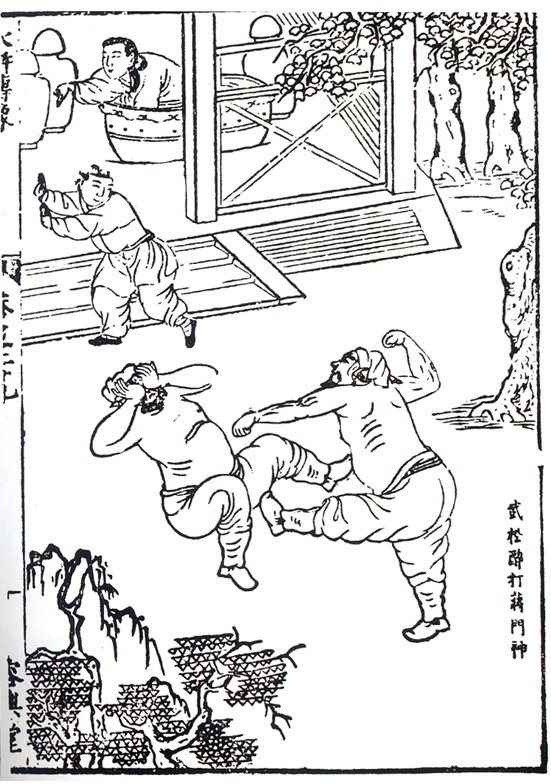

Caption in Chinese in the lower right: “Wu Song attacks Jiang the Door God.”

右下方的中文标题是:“ 武松攻击蒋门神。”(注:武松醉打蒋门神)

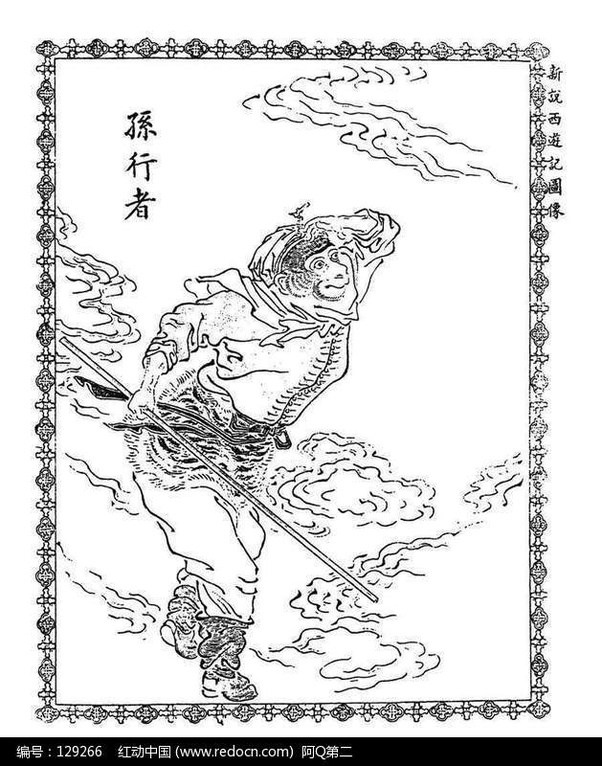

“Sun Xingzhe” - Sun the Ascetic, another title for Sun Wukong

“ 孙行者 ”——太阳苦行者,孙悟空的另一个头衔

The burning of Cao Cao’s fleet during the Battle of Red Cliffs.

曹操的舰队在赤壁之战中被烧毁。

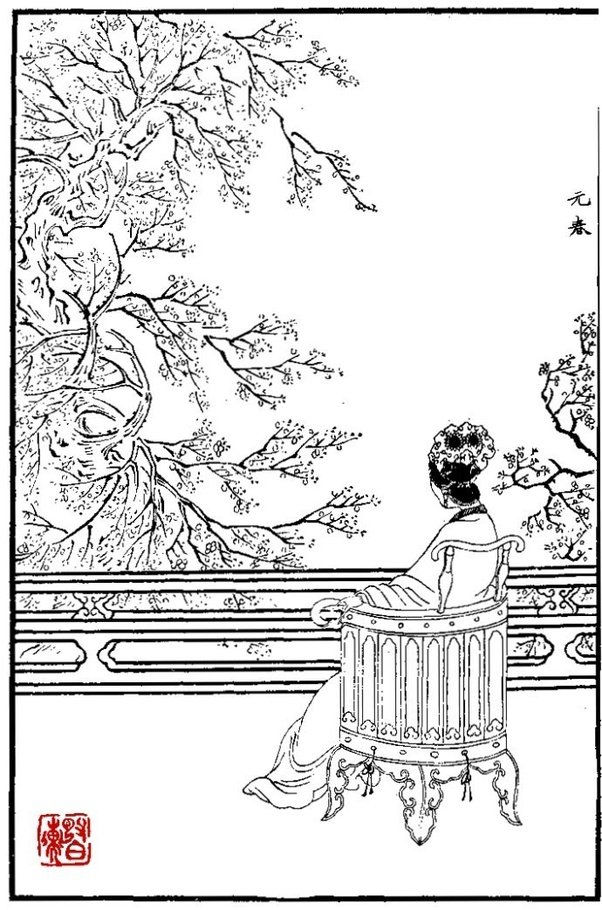

A woodcut of Jia Yuanchun, Jia Baoyu’s elder sister, and later an imperial concubine, looking out over Dayuan Garden. She would later die in her quarters at a detached, faraway area of the imperial palace at the age of 42.

贾宝玉的姐姐,后来成为皇妃的贾元春的一副木刻图,她俯瞰着大院花园。年仅42岁就死在了她在故宫的住所里,那里离她的家很遥远。

Of these four, the first two are largely about war. The Water Margin starts with the bandits fighting against the Song and ends with the bandits in the employ of the Song, invading the Liao Dynasty. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, of course, tells the story of the lengthy period of civil war before and following the final fall of the Han.

The Journey to the West is largely built on the mechanism of the travelers, especially Sun Wukong (孙悟空) fighting hordes of demons. You could go so far as to say that Sun Wukong is probably the most recognizable and perhaps the most beloved character in Chinese popular culture - but he is at the heart, a martial character and uses his powers in battle.

Of the four, only The Dream of the Red Chamber is wholly peaceful.

这四部书,前两部主要是关于战争的。“水浒传”以山匪反宋为开端,最后以山匪加入宋军反抗辽国的入侵结束。

“三国演义”则讲述了汉朝最终沦陷前后漫长的内战时期。

“西游记”在很大程度上是建立在旅行者的机制之上的,尤其是孙悟空对抗成群的恶魔。

你甚至可以说,孙悟空可能是中国流行文化中最具辨识度、也是最受欢迎的人物--但他是武力角色,在战斗中使用自己的力量。

在这四部书中,只有红楼梦是完全和平的。

So, let’s consider that. These were the most popular vernacular novels, often born of and recorded from popular storytellers - a form a pop culture in continuum of literacy experienced by the people during the Imperial era. All but one of them are primarily about war and fighting. Other popular vernacular novels, such as The Biography of Yue Fei (岳飞传) and The Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), also feature war as a major theme or backdrop. Their modern descendants in the wuxia genre - for instance, Jin Yong’s Condor Trilogy (射鵰三部曲) - take after them a great deal, and Yue Fei is upheld as a culture hero in his battles against the Jin.

All in all, these popular, traditional novels almost all feature war as a central theme or backdrop. That doesn’t mean that the Chinese people are inherently cruel and warlike, but it’s also not a sign that the Chinese people are exceptionally peaceful.

这些是最受欢迎的白话小说,通常是由通俗的说书人创作和记录的--这是一种通俗文化,是人们在帝国时代所经历的一种通俗文化。除了红楼梦外,其他都是关于战争和战斗的。

其他流行的白话小说,如“岳飞传”和“封神演义”,也以战争为主题或背景。

它们的现代版后裔是武侠题材--例如金庸的“射鵰三部曲 ” --很大程度上继承了它们,岳飞在与金人的战斗中被认为是一个文化意义上的英雄。

总之,这些通俗的、传统的小说几乎都以战争为中心主题或背景。

这并不意味着中国人民天生就是残忍和好战的,但这也不是中国人民异常和平的标志。

But, “ah,” you say, “what about Traditional Chinese culture! Buddhism and Taoism and Confucianism can’t be too warlike.”

Well, to some degree that’s correct. But we find ample evidence of a bellicose traditional Chinese culture. The most important, probably, is the Battle of Muye - a battle which, in the telling, would become the archetype for just war in terms of scouring vice and promoting virtue. It would also be used as the cornerstone of the dynastic cycle - a vigorous, just dynasty ousting an older, moribund, immoral dynasty - in the historiography of traditional Chinese writing, especially by writers such as Sima Qian.

We can find references to this in the Shijing in the Great Odes:

但是,你可能会说“ 啊,那中国的传统文化呢!佛教、道教、儒家思想不能太好战。“

在某种程度上这是对的,但我们也发现大量的证据表明中国传统文化好战。。。

我们可以在“诗经”中找到这方面的参考文献:

(Da Ming, 236:)

(《诗经 · 小雅 · 大明》:236)

殷商之旅、其会如林。

矢于牧野、维予侯兴。

上帝临女、无贰尔心。

牧野洋洋、檀车煌煌、驷騵彭彭。

维师尚父、时维鹰扬、凉彼武王、肆伐大商。

会朝清明。

Translated by Arthur Waley:

The armies of Yin and Shang,

Their catapults were like the trees of a forest.

They marshalled their forces at Muye

A target set up for us.

"God on high is watching you;

Let no treachery be in your hearts."

The field of Muye spread far,

The war chariots gleamed,

The team of white-bellies was tough,

The captain was Shang-fu;

Like an eagle he uprose.

Ah, that King Wu,

Switfly fell upon Great Shang,

who before daybreak begged for truce.

由亚瑟 · 威利翻译:

(注:亚瑟 · 韦利,英国着名汉学家 文学翻译家)

殷商的军队,

他们的弹弩就像森林里的树木。

他们在牧野集结他们的部队。

他们是我们的目标。

“上帝在高处注视着你;

你们心中不可有诡诈的事。“。

牧野的田野蔓延得很远,

战车闪闪发光,

驷马健壮雄骏,

尚父像雄鹰一样睥睨战场,

辅佐着武王,

转机落在大商身上,

他们将在黎明前祈求停战。

The Battle of Muye was a key point not only in terms of the end of the Shang, but also in developing the very basics of the legitimacy of the Zhou and, given the influence of Zhou political theory on future Chinese dynasties, the basics of legitimacy in other dynasties:

Not only did [the battle of Muye] result in the establishment of a Zhou hegemony in northern China that would endure for centuries and provide the nucleus from which an identifiably “Chinese” civilization would emerge, but it also came to acquire iconic status as the archetype of the legitimate use of armed force to accomplish what is today known as “regime change.”[….]

牧野之战不仅是商代终结的关键,也是建立发展周朝合法性基础的关键,同时,考虑到周朝政治理论对未来中国王朝的影响,也是其他朝代合法性的基础:

“牧野之战”不仅在中国北方建立了持续数个世纪的周朝霸权,提供了一个可辨识的“中华”文明的核心,而且也获得了作为合法使用武力的典范来完成今天所谓的“政权更迭”的典型地位。

The story put out by the Zhou victors, reflected and elaborated in the writings of their descendants many centuries later, is that the battle of Muye was a dramatic confrontation between virtue and vice. The last Shang king appears as a monstrous caricature of lust and cruelty, the inventor of fiendish new tortures who presided over orgies amid forests of meat and pools of wine and cut open the body of one of his advisers to find out whether the heart of a sage had seven apertures. The Zhou founders, in contrast, are presented as paragons of virtue and champions of righteousness. In some versions of the Muye story, the battle was one-sided and virtually bloodless as the Shang fighting men turned their weapons against their own leaders. The Zhou tradition held that the outcome was due not simply to a revolt of the oppressed against their oppressors, but to divine intervention bestowing military success and political legitimacy — the “Mandate of Heaven” (tian ming) — upon men of virtue.[1]

The Book of Documents, China’s arguably first work of history, records (or purports to) King Wu’s proclamation on the eve of battle against the Yin-Shang, some extracts of which are given here (all errors are my own, lixs to each section given in the incipit):

几个世纪后,周的胜利者在后世的着作中所反映和阐述的故事是,牧野之战是一场道德与邪恶的戏剧性对抗,上一任商王似乎是一幅描述欲望和残忍的可怕漫画,他是一种新酷刑的发明者,他在肉林和酒池中主持狂欢,并切开他的一位顾问的身体,以查明圣人的心脏是否有七个孔。

与之相反的是,周的创立者被认为是美德的典范和正义的拥护者。在某些版本的牧野之战故事里,这场战斗是一边倒的,几乎没有流血,因为商的战士把他们的武器对准了自己的领导人。

周朝传统上认为,结果并不仅仅是被压迫者反抗压迫者,而是神的干预,将军事成功和政治合法性--“天命”--赋予了有道德的人。

“书经”是中国的第一部历史着作,它记载了 ( 或声称是 ) 武王在与殷商开战前夕的声明,其中的一些摘录在这里:

I, child that I am beside my deceased father, have been apprehensive night and day. I have received the command of my deceased father, Wen, and I have sacrificed to the Emperor On High and I have performed my rites to the mighty earth, and so I possess the multitude by which I shall bring about the vengeance of Heaven. Heaven sympathizes with the people - all that the people should desire, Heaven shall grant. Shall you aid me, I who am chosen to cleanse the land between the four seas forever? The time has come! We cannot let it pass!

[…]

I have heard that good men, doing works of virtue, find the day too short. Evil men, committing vice, also find the day too short. The present King of Shang, Shou, commits his iniquities through violence and force. The illustrious elders he scatters and discards; he associates and is intimate with the sinners of his court. He is lascivious, obscene, a drunkard and oppressive to all and all his ministers have become like him. They form cliques and attack one another, they pursue power to exterminate one another. The innocent implore heaven! The stink of the dirt of this court reeks to the heavens!

We see here that the Battle of Muye fit very much into Zhou and, later, Chinese political theory stating that a military expedition and war against unrighteousness was not only permissible but mandatory on the part of the virtuous.

予小子夙夜祗惧,受命文考,类于上帝,宜于冢土,以尔有众,厎天之罚。天矜于民,民之所欲,天必从之。尔尚弼予一人,永清四海,时哉弗可失![…]

我闻吉人为善,惟日不足。凶人为不善,亦惟日不足。今商王受,力行无度,播弃犁老,暱比罪人。淫酗肆虐,臣下化之,朋家作仇,胁权相灭。无辜吁天,秽德彰闻。

——小子我想起我已故的父亲,日夜忧心忡忡,我已经决定接受已故父亲文的命令,我向至高无上的上天献祭,我也为大地举行了仪式,因此我拥有了众多的力量,我将以此来实现来自天堂的复仇,上天同情人民--人民所渴望的一切,上天都会给予。你愿意帮助我吗?我是被选中来永远净化四海之间的土地的人!时机已到!我们绝不能错过!

——我听说做善事的好人觉得日子太短了,作恶的人,也觉得日子太短了。现在的商王纣,用暴力和武力犯下了他的罪孽。他离弃显赫的长老,与他宫廷的罪人交往,亲近他们,他好色、淫秽、醉酒、欺压众人,他的大臣也都像他一样,互相攻击,他们追求消灭彼此的力量,无辜的人只能恳愿上天!这个宫廷的污垢臭气熏天!

我们在这里看到,牧野之战对周朝的重要性,后来,中国的政治理论认为,军事远征和反对不义的战争不仅是允许的,而且是有道德强制性的。

But forms of militarism find expression in Chinese literature and thought beyond that. We can take, for instance, the first lines of the ever-popular 孙子兵法:

孙子曰:兵者,国之大事,死生之地,存亡之道,不可不察也。

Sunzi said: “Soldiering is the great affair of the state - the realm of life and death, the way of existence and destruction. It can under no circumstances be neglected.

We can certainly find echoes of this sentiment as far ahead as Ouyang Xiu’s 新唐书 - his rewriting of the Book of Tang. The fascicle on the military begins as such:

古之有天下国家者,未始不以德,而自战国、秦、汉以来,鲜不以兵。夫兵岂非重事哉!

Of those nations which have possessed all under heaven, their decline and fall and their stability and their chaos may have been through their virtue, but from the Warring States onto the Qin, the Han, and onward, few have foregone the use of the army. How important is this matter of soldiering!

但是尚武好战精神的表现形式在中国文学和思想中表现得远远不止这些。例如,我们可以拿一直流行的孙子兵法的第一行为例:

孙子曰:兵者,国之大事,死生之地,存亡之道,不可不察也。

(孙子说,战争是一个国家的头等大事, 关系到军民的生死, 国家的存亡, 不能不认真地观察和对待。)

当然我们也可以在欧阳修编纂的“新唐书”里找到这种情感的共鸣,他重修了唐代史,关于军队的分册是这样开始的:

古之有天下国家者,未始不以德,而自战国、秦、汉以来,鲜不以兵。夫兵岂非重事哉!

(天下的国家,他们的衰败、安定和混乱,可能是由于他们的美德,但从战国到秦汉,再到后来,很少有人放弃使用军队,可见军队是多么重要啊!)

And, no doubt, we have the substantial Zuo Zhuan (左传), much of which regards military affairs! We can continue this discussion of pre-Qin militaristic and military-focused writing - from the chapters on siege warfare in the Mozi (墨子) to the varied discussions of war and battle in the Strategems of the Warring States (战国策) and the Discourses of the States (国语) - and that’s not even going into the relatively popular schools dedicated entirely to military affairs.

So, even in the early formation of Chinese culture during the Zhou, Warring States, and Spring and Autumn periods, we have a constant discussion of military affairs. Political matters were colored, in part, by the concerns of endemic warfare. So Chinese culture during its formative period was extensively affected by distinctly non-peaceful matters.

And what about the course of the dynasties? Certainly, I can get into a far longer discussion about the nature of Chinese imperial foreign policy, the attitude of the Chinese court with regard to those beyond its borders, and so on, but I want to take a look specifically at poetry - basically, the premier avenue for cultural expression for literate Chinese.

毫无疑问,我们也可以从《左传》中找到这些,其中大部分是关于军事的!我们可以继续讨论先秦军国主义和以军事为中心的作品--从墨子的“ 战国围城战 ”章节到《战国策》和《国语》中关于战争和战斗的各种讨论--而这甚至还没有深入到比较受欢迎的专门讨论军事事务的学校。

因此,即使在周代、战国和春秋时期即中国文化形成的初期,中国人也经常讨论军事问题,政治问题在一定程度上是受局部战争的影响,中国文化在其形成时期受到了明显的非和平事件的广泛影响。

那历朝历代的呢?当然,我可以就中华帝国外交政策的性质、中国宫廷对其境外的态度等问题进行更长时间的讨论,但我想具体谈谈诗歌---这是有文化的中国人的主要表达途径。

Even here, we have militaristic concerns, informed by the circumstances of the dynasty at the time:

Any student of Chinese history knows that as a government China never ceased to be deeply engaged in its foreign relations, as any successful polity must be; there were, however, long periods when the majority of writers and intellectuals were not interested in the world outside China. This was not true in the Tang. Throughout Xuanzong’s long reign the Tang was contesting control of Central Asia with the equally expansionist Tibetan kingdom and battling with the Khitan and Xi in the northeast. Tang armies reached what is modern Afghanistan, and in 751 an army under the Korean-born general Gao Xianzhi met an Arab army of the Caliphate at the Talas river. […]

Poetry about Chinese military experience in Central Asia had taken on its first mature form in the Southern Dynasties. Needless to say, the Han dynasty military ventures described in such poems were entirely products of the poetic imagination, responding to what poets had read in the old histories. Such poetry became highly conventional and those conventions continued to dominate frontier poetry in the seventh century, even for a poet like Luo Binwang who personally served with the Tang armies.

即使在诗歌里,我们也可以找到大量军国主义、尚武精神的表述:

任何学习中国历史的人都知道,作为一个政府,中国从未停止过对对外关系的深度介入,任何成功的政体都必然如此;

然而,在很长一段时间里,大多数学者和知识分子对中国以外的世界都不感兴趣。

但唐朝不是这样的。

在玄宗的长期统治期间,唐朝一直在与同样扩张主义的西藏王国争夺中亚的控制权,并与东北的契丹和奚作战。唐朝军队到达了现代的阿富汗,751年,出生于朝鲜的高仙芝将军率领的军队在塔拉斯河会见了阿拉伯哈里发国的军队。[…]

南朝时期,中国的中亚军事经历诗第一次呈现出成熟的形式。不用说,在这些诗中描述的汉代军事冒险完全是诗歌想象的产物,回应了诗人们在古代历史中所读到的东西。这种诗歌变得非常传统,这些习俗在七世纪继续统治着边疆诗歌,甚至像骆冰王这样的诗人也是如此,他本人曾在唐朝军队服役。

In Emperor Xuanzong’s reign there was a new vitality in frontier poetry. It was not that the historical context had changed: Tang armies had been deeply engaged in Central Asia in Empress Wu’s reign. Most of the poets who wrote about the frontier had never been there, as in earlier times. The change was in poetry itself and a new freedom of invention, which was at the same time a freedom of the imagination. Poets lamented the loneliness and suffering of the Tang troops, celebrated Tang victories, or wrote of the futility of the wars. [2]

The author then gives an example of one of Wang Changling’s poems from the 300 Tang Poems (唐诗三百首), for which I’ll include the Chinese:

玄宗时期边塞诗有了新的生命力。这并不是说历史背景发生了变化:在武皇后统治时期,唐朝军队曾深入中亚地区。大多数描写边疆的诗人从来没有像以前那样去过那里。这种变化体现在诗歌本身和一种新的发明自由上,这同时也是一种想象的自由。诗人们哀叹唐朝军队的孤独和苦难,庆祝唐朝的胜利,或者描写战争的徒劳无功。[2]。

这是一首王昌龄的诗,来自《唐诗三百首》 :

饮马渡秋水,水寒风似刀。

平沙日未没,黯黯见临洮。

昔日长城战,咸言意气高。

黄尘足今古,白骨乱蓬蒿。

I let my horse drink, crossed autumn waters,

the water cold, the wind like a knife.

Before the sun sank on level sands,

I could see Lintao in the glowing dark.

By the Great Wall they battled in olden days,

and say how high their mettle was.

Brown dust aplenty, both now and then

and white bones tangled in the brush.

我让我的马喝水,越过秋水,

水冷,风如刀。

在太阳落山前,

在漆黑的夜色中,我能看见临洮。

过去的日子里,他们曾在长城边上战斗,

他们的勇气多么高昂。

棕色的灰尘漫天飞舞,无论古今。

白色的骨头缠绕在灌木丛中。

We have another poem by him, Crossing the Border (出塞):

还有一首他的诗,《出塞》:

秦时明月汉时关, 万里长征人未还

但使龙城飞将在, 不教胡马度阴山

The brilliant moon stretches back to Qin, the passes to Han,

Ten thousand li march the troops without returning.

But may the capital of the Dragon make use of the Flying General,

So the Tartar Horseman shall never pass the Yin mountains!

明月回溯至秦,传至汉,

万里行军无人归返。

只希望龙之都能用飞将军,

这样鞑靼骑士将永远无法通过阴山!

And then, as another example, Cen Can (岑参) and his poem A Song of Running-Water River in Honor of the Departure of General Feng’s Western Expedition (走马川行奉送封大夫出师西征):

另一个例子,作者是岑参,《走马川行奉送封大夫出师西征)》:

君不见, 走马川行雪海边,平沙莽莽黄入天。

轮台九月风夜吼,一川碎石大如,随风满地石乱走。

匈奴草黄马正肥,金山西见烟尘飞,汉家大将西出师。

将军金甲夜不脱,半夜军行戈相拨,风头如刀面如割。

马毛带雪汗气蒸,五花连钱旋作冰,幕中草檄砚水凝。

虏骑闻之应胆慑,料知短兵不敢接,军师西门伫献捷。

Advancing to the Song, especially after the Jingkang Incident, we have the famously martial, revanchist poems of Lu You. Taking two of his most famous poems, Rainstorm on Nov. 4th (十一月四日风雨大作) and To My Son (示儿) :

到了宋代,在靖康事件之后,我们有了着名的陆游诗人的军事战争题材的诗歌,这里是他最着名的两首诗,《十一月四日风雨大作)》,和《示儿》:

僵卧孤村不自哀,尚思为国戍轮台。

夜阑卧听风吹雨,铁马冰河入梦来。

In a lonely village stiff I lie, no self pity,

Still I dream of serving at Luntai.

Laying in the dead of night the wind and rain I hear

Armored cavalry over icy waters, flowing into dreams.

在一个孤独的村庄里,我躺着,没有自我怜悯,我仍然梦想着在轮台服役。在夜深人静的时候,我听到了风雨中装甲骑兵越过冰冷的海水,进入我的梦乡。

死去原知万事空,但悲不见九州同。

王师北定中原日,家祭无忘告乃翁。

Dying now, what I did and knew was vanity,

But sorrow burns in my breast that my homeland is divided.

When the day comes his Majesty’s army sweeps the north and the heartland,

Oh, my son, remember to come and your father in his grave.

现在我死了,我所做的和知道的都是空洞的,

但我的祖国被分裂,我的心中燃起了悲伤。

当陛下的军队横扫北方和中原的时候,

啊,我的孩子,记得来你父亲的坟前,告诉你的父亲。

Now, certainly, these are differentiated by context, hundreds of years, intervening politics and literary development - and that’s very much the point, isn’t it? These are not peaceful poems - they’re poems celebrating or pushing for war and at least one is one of the most famous of all Chinese poems (To My Son). All of them are routinely found in anthologies of Chinese poetry, and the first three are included in perhaps the most famous book of Chinese poetry besides the Shijing, and To My Son is often a rallying cry for Chinese patriotism. But does this reveal an inherent desire for war in Chinese culture?

Absolutely not. It means that within Chinese culture there are authors and creators and thinkers that deal with the matter of militarism and may, individually, choose to make that a focus of their creation. There are themes, concepts, forms and conventions that repeat themselves, but it’s hard to see how that makes China singularly militaristic.

当然,这些诗歌是有历史背景的,几百年来干预政治和文学发展,这是很重要的一点,不是吗?这些不是和平诗--它们是庆祝或推动战争的诗歌,至少有一首是(《示儿》) 最着名的中国诗歌之一。上述几首诗经常出现在中国诗歌选集中,前三首被收录在或许是除《诗经》最着名的中国诗集中,《示儿》往往是对中国爱国主义的号召,但这是否揭示了中国文化中固有的战争欲望呢?

绝对不是。这意味着的是,在中国文化中,有作家、创作者和思想家在处理军国主义问题,并可能个别地选择将军国主义作为他们创作的重点,有一些主题、概念、形式和惯例在重复,但很难看出这是如何使中国变得异常军国主义的。

To refer to any culture as specifically aggressive, peaceful, totalitarian, freedom-loving or by any such term is an exercise in futility. Cultures aren’t monolithic - they’re the products of innumerable individuals, all coming from individual circumstances and experiences. There’s not even any explanatory power behind it - it’s impossible to separate a country’s actions from historical, economic, and political context, which are usually sufficient in themselves.

In short, culture may inform a people, but it does not strictly govern them - As such, terming any culture as monolithically anything is quixotic at best.

把任何一种文化称为具有侵略性的、和平的、极权主义的、热爱自由的或用任何这样的术语来形容都是徒劳的。文化不是一成不变的---它们是无数个人的产物,来自个人所处的环境和经历,它的背后甚至没有任何解释力--不可能把一个国家的行动与历史、经济和政治背景分开,而历史、经济和政治背景本身通常就足够了。

简而言之,文化可能会促使形成一个民族,但它并不严格地支配着他们,将任何文化简单的描述为单一的某一属性都是不切实际的。

(注:有删减,中间有一段对德国,俄国类似诗歌的分析,限于篇幅不放上来了。)

In any culture, there are statements of sorrow, of joy; of aggression, of peace; of idealism, of cynicism; of skepticism, of faith. To try and narrow down A Culture as a monolithic thing that can be described through a singular adjective is to put blinders on yourself - cultures are more interesting as the sum of human experience than they are as a way to classify people or attitudes.

在任何文化中,都有悲伤,欢乐;侵略,和平;理想主义,愤世嫉俗;怀疑,信仰。试图将文化缩小为一个单一的东西,可以用一个单数形容词来描述,这是在蒙蔽你自己---文化作为人类经验的总和比它们更有趣,文化不是用来对人或态度进行分类的一种方式。

Footnotes

[1] The Prism of Just War 《战争棱镜》

[2] The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature 《剑桥中国文学史》

———————————————————

Sun Xiuqi, former Supreme Admiral at Mongolian Navy

Sun Xiuqi,前蒙古海军最高司令

Cultures cannot be characterized by the simple parameters of 'peaceful' and 'warlike'. Cultures are subject to change and are shared by a diverse group of human beings who may or may not fit the definition of 'peaceful' or 'warlike'.

China is so large and diverse there are certain regional groups of Chinese people who have retained a 'warlike’ and savage nature that could rival the Vikings or Vandals: those Chinese people who live along the banks of the Huai River can be most likened to the Vandals of late Antiquity:

文化不能以“和平”和“好战”这两个简单的参数为特征。文化是有变化的,不同的人类群体可能符合也可能不符合“和平”或“好战”的定义。

中国幅员辽阔,人口众多,有些地区的中国人保持着“好战”和野蛮的天性,可以与维京人或凡达人相提并论:那些生活在淮河两岸的中国人最常被比作古代的破坏者:

The Nian Rebels of the mid-19th century.

19世纪中叶的捻军叛乱者:

The formidable Anhuinese Infantrymen of the Huai Army:

淮军中强大的安徽人步兵:

Wherever they went, they pillaged, raped and killed with impunity. The harsh environment their people lived in encouraged intense tribalism and a medi 'Revenge Culture'. The tradition of the local lord's'first right'to bed all newlywed brides in the village was practiced well into the 20th century in these areas. Even today people from the Huai River basin are considered'less civilised' by many Chinese.

无论他们走到哪里,他们都抢劫、强奸和杀害而不受惩罚。当地人所处的恶劣环境助长了激烈的部落主义和中世纪的“复仇文化”。村里所有的新婚新娘第一夜属于领主,这种“初夜权”的传统在这些地区一直延续到20世纪,即使在今天,淮河流域的人们仍然被许多中国人认为是“不那么文明”。

The Hunanese:

Zeng Guofan(Hunanese himself): Hunan is to China what Sparta is to Greece. Nuff said.

Even today Hunanese are unlike most other Chinese regional groups by considering soldiering a very respectable profession, and they comprise a significant portion of the PLA Land Forces.

湖南人:

曾国藩:湖南对中国就像斯巴达对希腊一样。这句话足够说明一切了。

即使在今天,湖南人也与大多数中国其它地区的人不一样,并认为当兵是一种非常受人尊敬的职业,而且他们在解放军陆军作战部队中占有相当大的比例。

The Minnan Peoples:

Zheng Chenggong:

Wang Zhi:

These were East Asia's answer to the Vikings of old. These hardy seaborne raiders were feared throughout the West Pacific from the 14th to the mid 19th centuries, and a force to be reckoned with. They founded numerous immigrant colonies and states in what is now Southeast Asia.

Taiwan under Zheng Chenggong, better known as Koxinga in western sources, was basically a pirate state.

闽南人:

郑成功:

王直(注:着名的海盗,但中国历史书基本很少提到他):

他们是东亚的维京人。从14世纪到19世纪中期,这些海上掠夺者在整个西太平洋地区都很可怕,而且是一股不可忽视的力量。他们在现在的东南亚建立了许多移民殖民地和国家。

郑成功统治下的台湾,在西方被称为科辛加( Koxinga,国姓爷的意思 ),基本上就是一个海盗国家。

So are these Chinese cultures peaceful? Generally Chinese people are peaceful, but don't mess with us or these guys will pillage your towns, defeat your armies and raid your coasts!

那么,这些中国文化是和平的吗?一般来说,中国人是和平的,但不要惹我们,否则这些人会掠夺你们的城镇,打败你们的军队,袭击你们的海岸!

———————————————————

Magnus W. Magnusson, Living in China for 20 years and counting, speaking the language and reading it

马格努斯·W·马格努松,在中国生活了20年,能算、能说、能读。

As there is no agreed measure for ‘peacefulness’ one cannot claim that one culture is more or less peaceful than any other.

Looking at Chinese movies and TV, it does not seem to be a particularly peaceful culture. According to some estimates about 700mio Japanese die on-screen every year in China. Martial art heroes abound in all ages of China (according to TV). I see even very young kids play with realistic toy guns etc., aiming them at others without being admonished by their parents.

Also China did not reach its current extent by peaceful means only. Also China has in its history rocked by events of cataclysmic violence, for example the Taiping revolution, the warring states, even the Chinese civil war(s) of the 1920s and 30s. The cultural revolution was not peaceful at all. Neither was the unprovoked attack on Vietnam in 1978.

That does not mean that China is less peaceful than other countries. Yet the official propaganda of China is that China is peaceful, is more peaceful than other countries and this is what is being taught in schools. Thus Chinese are convinced that their culture is peaceful (even though they take inordinate pride in their military might).

(it is interesting to note that many Chinese argue that they as ‘rice eaters’ are more peaceful than western ‘meat eaters’. Not only did people in the West until about the 1920s eat very little meat, at the same time also Japanese have pointed out to me that they as rice-eaters are more peaceful than we Westerners…….)

由于没有确定的“和平”衡量标准,人们不能声称一种文化是否比另一种文化更和平。

看看中国的电影和电视,它似乎不是一种特别和平的文化。

据估计,在中国,每年约有7亿日本人死于银幕上。中国各个时代都有武术英雄。我看到,即使是非常年幼的孩子也会玩逼真的玩具枪,把它们瞄准别人,而不会受到父母的警告。

此外,中国不只是通过和平手段达到目前的程度。

此外,中国历史上也曾发生过严重的暴力事件,如太平天国、战国,甚至20世纪二三十年代的中国内战,文化大革命一点也不和平,1978年对越南的无端攻击也不是。

这并不意味着中国不像其他国家那么和平。

中国官方的宣传是,中国是和平的,比其他国家更和平,这就是学校所教的。因此,中国人相信他们的文化是和平的( 尽管他们对自己的军事力量感到异常自豪 )。

( 有趣的是,许多中国人认为他们是“食米者”,比西方的“肉食者”更和平。实际上,在20世纪20年代以前,西方人很少吃肉,同时日本人也向我指出,他们也是吃米饭的,比我们西方人更和平。。。)

———————————————————

Michel McGill, Born, lived and worked in China.

米歇尔麦吉尔,出生,生活在中国,工作在中国。

Comparatively, yes! Talking about culture, we have to see what it values. To see what it values, we look for what it worship. The West worships the God. In the Bible, Exodus 15:3 “The Lord is a warrior; the Lord is his name”. In the Old Testimony, we see that the God is very violent by destroy human with disasters. That is the figure the West worships. China worship Confucius. Confucius is a scholar devoted to education. Education is the Chinese religion. Every major cities in Europe have the status of the Goddess of Victory, a worship of war. European historians adore conquerors, such as Alexandra the Great and Julius Caesar the dictator. By contrast, Qin Shi Huang and Emperor Wu of Han never get such a high position as Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar get in the West. Qin Shi Huang and Emperor Wu of Han have not favorable position in Chinese historians and literature. Qin Shi Huang has long been condemned in Chinese history as a dictator. Highly praised historical figures in China are Confucius and Laozi, the philosophizers. There temples of Confucius and Taoism all over China. Every emperor gave ceremony to worship Confucius. Even the military achievements of Qin Shi Huang and Emperor Wu of Han are not named conquer, but unification.

The only Warrior God Chinese worship is the Guan Yu, you can see it in many Chinese restaurants. Chinese worship no because his military power, but because of his devotion to Confucianism.

Chinese worship Guan Yu as much as European worship Napoleon, but for different reason. Chinese is not worship his military achievement.

Goddess of Victory. The worship of War.

Goddess of Victory. The worship of War.

相对而言,是的!说到文化,我们必须了解它的价值。为了了解它的价值,我们寻找它崇拜的东西。

西方崇拜上帝。在圣经里,出埃及记15:3“耶和华是勇士,耶和华是他的名”。在旧约的记录中,我们看到神是非常暴力的,用灾难毁灭人类。这是西方崇拜的人物。

中国崇拜孔子。孔子是一位致力于教育的学者,教育是中国的宗教。

欧洲各大城市都有胜利女神的雕像,这是一种对战争的崇拜。欧洲历史学家崇拜征服者,如亚历山大大帝和凯撒大帝。

相比之下,秦始皇和汉武帝从未获得过亚历山大大帝或凯撒大帝在西方的那样高的地位。秦始皇和汉武帝在中国史学界和文学界地位不高,秦始皇作为独裁者在中国历史上一直受到谴责。

在中国受到高度赞扬的历史人物有孔子和老子,他们都是哲人,中国各地都有孔庙和道观。

每个皇帝都要举行仪式敬拜孔子,即使是秦始皇和汉武帝的军事成就也不是“征服”,而是“统一”。

中国人唯一崇拜的战神是关羽,你可以在许多中国餐馆看到它。

中国人崇拜他不是因为他的武力,而是因为他对儒学的热爱。

中国人崇拜关羽和欧洲人崇拜拿破仑一样,但原因不同,中国人并不崇拜他的军事成就。

胜利女神。对战争的崇拜。

胜利女神。对战争的崇拜。

————————————————

皓阳 李, studied at Huazhong University of Science and Technology

李皓阳,在华中科技大学学习

Yes,but no.

It depends.

Chinese culture is just like water.

You could see water in a peaceful lake but you can also see water in the stormy ocean.

When nothing stimulates China,it has no interests in wars at all. About this you could see the familiar scene over and over again in the history of China. It works hard to survive while being invaded and right after it sustain its existence, it starts to settle down to keep what it had had.

You could see the Qin dynasty built the Great Wall to defend itself instead of sending military forces outside to vanish the threat from Huns.

And Han dynasty sent a princess to the king of Huns for peace right after it reunited China again.And it hadn’t started any wars until the Huns came back again and the emperor had to send messengers to combine Darouzi(a country in the central Asia) for defeating Huns.Then we had the silk road.

You could see the Jin dynasty even dismissed its central troops after the emperor reunited China.And it was that to blame for the coming chaos in China directly caused by the invasion of Nomads form the north.

There are so many examples in which you could find that China is nothing about expansion. Everything it intends to do is to live its own life.

But you could also find that whenever something stimulates (disturbs frequently,invades and so on)it, China will never give up gaining its own peace.

是,但也不是。

这要看情况。

中国文化就像水一样。

平静的湖水是水,狂风暴雨的海洋也是水。

当没有东西刺激中国时,它对战争毫无兴趣。

关于这一点,在中国的历史上,你可以一遍又一遍地看到这种熟悉的景象。

当它被入侵时,它努力生存,在维持它的生存之后,它开始安定下来,以保持它曾经拥有的东西。

你可以看到,秦朝建造长城是为了自卫,而不是为了消除来自匈奴的威胁而向外派遣军队。

汉朝又一次统一了中国,就派了一位公主到匈奴王那里寻求和平,直到匈奴再次劫掠,皇帝不得不派使者联合大月氏( 中亚的一个国家 ) 才发动了战争,打败了匈奴,然后我们就有了丝绸之路。

你可以看到,在皇帝统一中国之后,晋甚至解散了中央军队,这也是导致北方游牧民族入侵直接造成中国混乱的罪魁祸首。

有这么多的例子,你可以发现,中国与扩张无关。

它想做的一切就是过自己的生活。

但你也会发现,只要有什么东西刺激 ( 频繁的干扰、入侵等等 ),中国就永远不会放弃获得自己的和平。

————————————————

Yugan Talovich, Live in Taiwan, study Chinese lit and history.

Yugan Talovich,生活在台湾,学习中国文学和历史。

Of course Chinese history has its fair share of wars, rebellions, and massacres, but overall I would say that Chinese culture is peaceful. Other people have discussed this at some length, but I would like to add that in Chinese literature, especially during the formative period, say from Shang to Han, you do not see the glorification of blood and gore that you see in, say, the Iliad, Beowulf, or even the Bible. The only place you see praise for war is in 诗经秦风 part of the Odes.

Even Sun Tze 孙子兵法 in the Art of War said that conquering cities is not the best way to deal with your enemies. 善用兵者,屈人之兵,而非战也;拔人之城,而非攻也 Someone who is good at using his army beats the enemy without fighting, takes their castles without attacking them.

汉高祖 the founding Emperor of the Han said, 斗智不斗力 I fight with my wits, not with my strength. Chinese culture places more emphasis on strategy than violence.

当然是和平的。

中国历史上也有战争、叛乱和屠杀,但总的来说,中国文化是和平的。其他人已经讨论了很长时间,但我想补充的是,在中国文学中,特别是在形成时期,从商到汉,你看不到像《伊利亚特》、《贝奥武夫》甚至《圣经》中那样对血腥的赞美和美化,你唯一能看到对战争的赞美的地方是在《诗经》诗篇的“秦风”部分。

就连“孙子兵法”中的孙子也说过,攻打城市不是对付敌人的最好方法(善用兵者,屈人之兵,而非战也;拔人之城,而非攻也)。

汉代开国皇帝汉高祖说:斗智不斗力(用智慧而不是蛮力来战斗)

中国文化更注重策略而不是暴力。

————————————————

Joanna Wong

The Taoism regards life as the blessing from the GOD/universe.

We humble living should bide by the theory of GOD/universe - TAO 道 DAO Taoism.

So, in the common consciousness of Han Chinese, Yes, China is a peaceful country.

The thing worthy to remind is that respecting peace is a personal quality that in blood, yet it doesn`t mean do nothing.

“As heaven maintains vigor through movement, a gentleman should constantly strive for self-perfection” - 天行健,君子以自强不息。

道教认为生命是上天/宇宙的恩赐。

我们谦卑的生活应该遵循上天/宇宙的理论----道家。

所以,在汉人的共同意识中,是的,中国是一个和平的国家。

值得提醒的是,尊重和平是一种浸入血液的个人品质,但这并不意味着什么都不做。

“上天通过运转来保持活力,绅士应该不断地为自我完善而努力”---天行健,君子以自强不息。

————————————————

Yang, lives in China (1995-present)

That depends on if you are our friend.

There is a motto in our culture:“朋友来了有好酒,敌人来了有猎枪。” It means : to our friends with good wine the enemy was to have a shotgun.

There is a trend in Chinese history. Literary academics,especially Confucian scholars,occupy more and more power in the government. And warriors are more and more marginalized in politics. Since Sui dynasty(about 581 AD.) established imperial examination system,Chinese culture increasingly discriminaties warriors and respects scholars.Literary academics,not warriors, help the emperor rule the country.

Now college entrance examination is the continue of imperial examination system.

In Chinese culture,force is not well received. The core thought of confucius is “仁”,which means humaneness.

At last,we do love peace,but it is not signify we afraid war. To our friends with good wine the enemy was to have a shotgun. If other countries invade us, we will band together and hit back,just as we did in China's eight-year War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

Wish for world peace.

那要看你是不是我们的朋友了。

我们的文化中有一个座右铭:“朋友来了有好酒,敌人来了有猎枪 ”

中国历史上有一种趋势,文学学者,尤其是儒家学者,在政府中占有越来越大的权力,而军人在政治上也越来越被边缘化。

隋朝 (公元581年左右) 建立科举制度以来,中国文化日益歧视武士和尊重学者,帮助皇帝统治国家的不是武士而是文学学者。

现在高考是科举制度的延续。

在中国文化中,武力并不受欢迎。孔子的核心思想是“仁”。

最后,我们确实热爱和平,但这并不意味着我们害怕战争。我们的朋友喝了好酒,敌人收获的是猎枪。如果其他国家侵略我们,我们就象中国八年抗日战争那样,联合起来反击。

希望世界和平。

————————————————

Peter Choi, BFA Illustration, California State University, Fullerton (2010)

Peter Choi,美国加州州立大学文理学院,富勒顿分校(2010)

I’ve read some ancient Chinese history books. Well, the stories of wars are peppered all over them, but what’s really striking is the depiction of tortures and executions.

It’s not just Chinese. East Asians are deceptively peaceful. The history of East Asia is drenched and written with blood, to the degree that Vlad Tepes looks like Gandhi compared to Asian warlords.

我读过一些中国古代的历史书。战争的故事比比皆是,但真正令人震惊的是对酷刑和处决的描绘。

不仅仅是中国人,东亚人表面上是和平的,东亚的历史充满了血淋淋的历史,与亚洲军阀相比,弗拉德·特佩斯(罗巴尼亚大公,异常残忍)看起来就像甘地。

————————————————

Ramaswamy Subramanian, Enrich your thoughts, and live a life of your own.

拉马斯瓦米·萨勃拉曼尼亚,丰富你的思想,过你自己的生活。

Any culture that is peaceful, cannot motivate their life-style for up-gradation. China is moving fast, in all social and economic activities, and thereby making way for, huge ups and downs. A peaceful culture is an isolated culture, but China has moved-up in all respect, globally, and is vulnerable, to all global conditions, both economically and militarily. A peaceful culture, has to be content, with what they have, and also to be happy with, what they do. Trying to integrate, and interact, more and more globally, but with life-style restriction, internally, are not signs of peace. Peaceful culture, should identify with individual freedom, but many socialistic culture ignored it. China is still riding on it.

任何一种和平的文化,都不能激励他们的生活向更高级的方向发展。

中国的社会和经济活动都在快速发展,为巨大的起起落落让路。

和平文化是一种孤立的文化,但中国在全球范围内的各个方面都有所进步,在经济和军事上都很容易受到全球环境的影响。一个和平的文化,必须满足于他们所拥有的东西,也要对他们所做的事情感到快乐。

试图在全球范围内进行整合和互动,但在内部限制生活的发展并不是和平的标志。

和平文化,应该与个人自由相一致,但许多社会主义文化忽视了它,中国仍在利用它。

————————————————

Mark Marley studied at Tamkang University

Mark Marley,在淡江大学学习

Go China to experience it,

All the West people were to ask the same question, we need to answer 700–800 millions times. Save our energy for god sake.

去中国体验一下,

如果所有西方人都问同样的问题,我们需要回答7亿到8亿次,看在上帝的份上,省省力气吧。

————————————————

Tony Stark

Yes I think so.

The main stream culture in educated people in ancient time is Confucius’ school, which one of the most important dogma is telling people to be kind.

是,我想是的。

古代受教育者的主流文化是孔子学派,其中最重要的教条之一就是告诉人们要善待人。

————————————————

Livy Zheng

No,if we are peacefull, there would not be so huge land we live.

不,如果我们是和平的,就不会有这么大片土地了。

————————————————

Zongping Li

Not like Islam destroy everything. Hah. Welcome to china , you will see.

不像伊斯兰教那样摧毁一切,哈,欢迎来到中国,你会看到的。

————————————————

Qiao Yu

no,it is not. What do you think of rooster liking Chinese territory come from?

不,不是的,你认为喜欢中国领土的公鸡是从哪里来的?

————————————————

Quora User

The answer to your question depends on the class of the person who answers your question.

But I think for you guys, it’s highly possible for you to take it for granted that Chinese are aggressive since ‘we’ are able to spend splendid money buying a mansion in Vancouver. But I would suggest you to spend a trip to China visiting different places, both the urban and suburban, then you might be able to gain a deeper understanding of China.

I am afraid that the ‘China’ that you learn from TVs or broadcasts outside mainland isn’t not what I feel of China as a Chinese, it’s a consensus that China is still a developing country.

你问题的答案取决于回答你问题的人的阶层。

但是我认为对于你们来说,你们很有可能理所当然地认为中国人很有侵略性,只因为 ' 我们 ' 可以花很多钱在温哥华买一栋豪宅。 但是我建议你去中国旅游,去不同的地方,包括城市和郊区,这样你就可以对中国有更深入的了解。

我担心你从大陆以外的电视或广播中学到的 '中国' 和我作为一个中国人的对中国的感觉会完全不一样,但中国仍然是一个发展中国家,这是一个共识。

———————————————————

Halfman Huang, the God of justice, the guardian of freedom, the terminator of law, the messager of mao.

Halfman Huang,正义之神,自由的守护者,法律的终结者,毛的信使。

China has many culture, which one you mean?

Confucian, I am a teacher, and you are all students, listen to me or die in a bloody hell, pretty like a lighthouse shit you-know-the-name in current world.

Taoist, War! What is the war? Let me think……100 years later……damn, I just cannot find the answer.

Mohist, I don’t want to fight, but you want a fight, yeah, Let’s go fight and I am pretty damn good at it.

Legalist, kill them all! kill them all! Let the city burn! burn to hell! Humanity? WTF Humanity is…

中国有很多文化,你指的是哪一种?

儒家,我是老师,你们都是学生,听我的话,否则你还是去死好了,就像当今世界的某个灯塔国,你知道名字的。

道家,战争!什么是战争?让我想想……100年后……该死,我就是找不到答案。

释家,我不想打架,但你想打架,那就开打吧,其实我很擅长的。

法家,把他们全杀了!把他们全杀了!让城市燃烧吧!烧成地狱!人性? 人性是什么鬼。。

————————————————

Scott, works at The New York Academy of Sciences

斯科特,在纽约科学院工作

Yes and no. One of the fundamental differences between Chinese culture and that of the West is that the Chinese values, almost frantically, the concept of Unity.

When the Roman empire collapsed, Europe eventually was divided into dozens of nation-states. These nation-states didn't reunite Europe, but instead expanded outward via violent colonizations in order to gain resource to compete with other rival European nation-states. The division lasted till today. The European countries might become allies with each other for various reasons, but probably no one will ever expect Europe to reunite into a Roman-esque, one country state again.

China has also been divided into many nation-states, actually many times throughout her history. However, instead of being content with the division like Europe, China was willing to go through extremely violent and bloody civil war, sometime losing more than 80% of her population, in order to reunite. However, once they are united, China will become very peaceful again and almost never bothered to invading other countries.

This culture of Unity is not only displayed in the political level, you can also see such Unity in the Chinese society like in Chinese families, schools, businesses etc.

Therefore you can see that China is fairly peaceful in the international stage such as in trade and diplomacy. BUT, if there comes anything that threatens the Unity of China, such as the Taiwan issue, the Tibet issue, Diaoyu Islands etc, China can and will fight

是也不是。

中国文化与西方文化的根本区别之一是,中国人的价值观几乎是疯狂的执着于“ 统一 ”的概念。

当罗马帝国崩溃时,欧洲最终分裂成几十个民族国家,这些民族国家没有统一欧洲,而是通过暴力殖民向外扩张,以获得资源与其他竞争对手欧洲国家竞争,分裂一直持续到今天。由于各种原因,欧洲国家可能会成为彼此的盟友,但也许没人会指望欧洲会重新统一成一个罗马式的国家。

中国也被划分为许多民族国家,实际上在她的整个历史中有很多次。然而,中国并不愿于欧洲那样的分裂,而是愿意经历极端暴力和血腥的内战,有时甚至失去80%以上的人口,以重新统一。

然而,一旦他们统一起来,中国将再次变得非常和平,几乎从不费心去侵略其他国家。

这种统一文化不仅表现在政治层面上,在中国社会中也可以看到这种统一,如家庭、学校、企业等。

因此,你可以看到中国在贸易和外交等国际舞台上是相当和平的,但是,如果出现任何威胁到中国统一的问题,如台湾问题、西藏问题、钓鱼岛问题等,中国有能力也愿意为之进行斗争。

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10