贫穷是我的种族:非裔巴西人要求奴役赔偿 [美国媒体]

Almir Viera Pereira踩着田埂上干硬的枯草,为了在这一小片土地上耕作他已经奋斗了很多年,他抓起一把沙土,看着风把它从手中吹散,归于大地。巴西东北部的内陆地区因为干旱而著称,可以一连持续数年的干旱使得几代当地人逐渐迁徙到南方的工业城市,如圣保罗、里约热内卢、贝洛哈里桑塔,在那里的土地上休养生息,Barra do Parateca村则正在从去年的干旱中逐渐恢复。

Afro-Brazilians Demand Slavery Reparations Because ‘Poverty Has A Color’

非裔巴西人要求为对他们的奴役进行赔偿,因为“贫穷是我的种族”

Almir Viera Pereira holds a handful of dry soil on a patch of disputed land his group has claimed under Brazil’s constitutional right to reparations for descendants of runaway slaves. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

Almir Viera Pereira抓着一把干燥的泥土,根据巴西宪法这片土地属于他这种逃奴的后裔。

The dry grass crackled under Almir Vieira Pereira’s shoes as he walked along the edges of the roça, a small patch of land he’s been fighting to plant on for years. He grabbed a handful of soil and watched it puff into a smoky cloud as it settled back to the ground.

Almir Viera Pereira踩着田埂上干硬的枯草,为了在这一小片土地上耕作他已经奋斗了很多年,他抓起一把沙土,看着风把它从手中吹散,归于大地。

Brazil’s northeastern backlands are known for their dryness. Perennial droughts have sent generations of northeasterners fleeing from impoverished farming towns like this one for the industrial cities of the South — São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte. Barra do Parateca’s soil had yet to recover from last year’s lack of rain.

巴西东北部的内陆地区因为干旱而着称,可以一连持续数年的干旱使得几代当地人逐渐迁徙到南方的工业城市,如圣保罗、里约热内卢、贝洛哈里桑塔,在那里的土地上休养生息,Barra do Parateca村则正在从去年的干旱中逐渐恢复。

But dry or not, the ability to walk freely across this field marked a major victory for Pereira. He and a group of slave descendants from the roughly 1,500-person hamlet of Barra do Parateca have spent the last five years invading chunks of land across the area that they say are rightfully theirs under a well-known but haphazardly enforced article of the Brazilian Constitution. That law guarantees permanent, non-transferable land titles to Brazilians descended from the members of runaway slave settlements. Such communities of descendants are known in Brazil as “quilombos.”

但是就算这样干旱,能够在这片土地上自由行走对于Pereira来说也已经是巨大的胜利了。在过去的五年里,大约由1500人组成的小村庄Barra do Parateca中的这些奴隶的后裔们一直在为了占据这片根据巴西宪法属于他们的土地而努力,尽管这部分法令广为人知,却基本没有得到实施。法律给予那些曾经的逃亡奴隶的后裔“永远且不可变更”的土地所有权,而这些人在巴西组成的社群叫做“歌伦波”。

Brazil is the world’s fifth-largest country and relatively underpopulated, but land ownership remains out of reach most of the nation’s poor farmers, many of whose ancestors worked the fields for European overlords. The ability to plant one’s own food marks the first step for people like Pereira in a long march out of poverty and toward independence.

巴西拥有世界上面积第五大,而且人烟稀少的农村地区,但是绝大部分贫困的农民都没有自己的土地,他们的祖先世世代代都在欧洲殖民者的种植园里劳作。对于像Pereira这样的人来说,能为自己耕种粮食就是他们摆脱贫困,走向独立的第一步。

“Our fight for land is all about producing food,” Pereira, 39, said. “The great thinkers of the world, they’re thinking about creating things, inventing things. We’re still thinking about eating. If the government really wants racial reparations, they have to at least give us the possibility to think like equals.”

“我们奋斗这么多年只是为了种地,”39岁的Pereira说。“世上的那些聪明的大人物,他们整天想的是创造和发明,而我们的肚子还没有填饱,如果政府真的想缓和种族矛盾,他们至少应该给我们完成这细小愿望的能力。”

Four years ago, anyone who looked across this 15-acre plot would have seen razed earth littered with broken ceramic tiles that had once served as the roof of a camp shelter. The cops had wiped out that settlement after the neighbors who owned the land, the Pereira Pinto family, failed to persuade Pereira and his fellow quilombo residents to vacate the premises.

四年前,任何来到这片15亩土地的人都只能看到一片残砖破瓦,因为警察在当时的地主Pereira Pinto家族的要求下夷平了Pereira和他的“歌伦波”同伴们建起来的窝棚。

Pereira and his group had had several run-ins with authorities before, but this time was different. Normally, they would be allowed to finish the harvest if they agreed to abandon the plot when they were done. This time, police destroyed the crops in front of a crowd of Barra residents.

Pereira和他的伙伴们在这之前就和当局发生过几次冲突,但这一次冲突升级了。以往他们都会在收获庄稼之后才把这些居民驱逐走,这一次警察直接在他们眼前毁掉了这些庄稼。

“Everyone was crying and we couldn’t do anything,” Pereira’s friend, Ducilene Magalhães, recalled. “We just watched.”

“所有人都在无助地哭泣,”Pereira的朋友Ducilene Magalhães说,“然而我们只能这样看着。”

These days, Pereira and Magalhães have arrived at an uneasy truce with the landowners. Though the owners are in the midst of pursuing legal action and have removed an irrigation system that once watered the field, they’re also reluctantly allowing the quilombo members to harvest crops on a small patch of the property until the courts settle the dispute.

在那段时间里,Pereira和Magalhães艰难地与地主签订了一个协议,尽管地主仍然在用法律驱逐他们,还拆除了他们的灌溉设施,但同时也同意他们在一小片土地上耕作,直到法院最终作出判决。

Although quilombos dotted the Brazilian landscape throughout the era of slavery, which lasted from the 1500s until 1889, they faded into history during the 20th century. Most of the legislators who approved the quilombo law, ratified in 1988 as part of the new Brazilian Constitution, viewed it as a symbolic gesture that would affect only a handful of families.

从1500年代到1889年之间巴西的奴隶制历史上,“歌伦波”曾经在巴西大地上到处落地生根,但是在进入二十世纪之后这个名词也逐渐变成了历史。在1988年,《“歌伦波”法》加入巴西宪法时,大部分的立法者认为这只是一个象征意义的,影响不了太多人的法案。

But in 2003, a decree by left-wing President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva made it possible for virtually any black community to apply for quilombo status, if a majority of its residents so decided.

但是在2003年,左翼的总统卢拉签署了这样的法令,使得任何黑人社区都可以被定义成“歌伦波”,只要社区中的大部分人愿意,它就可以成为事实。

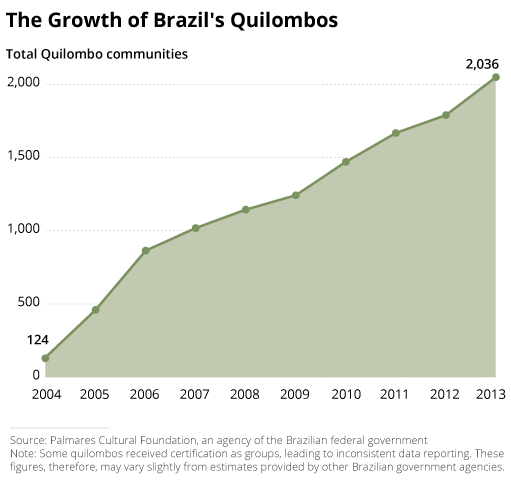

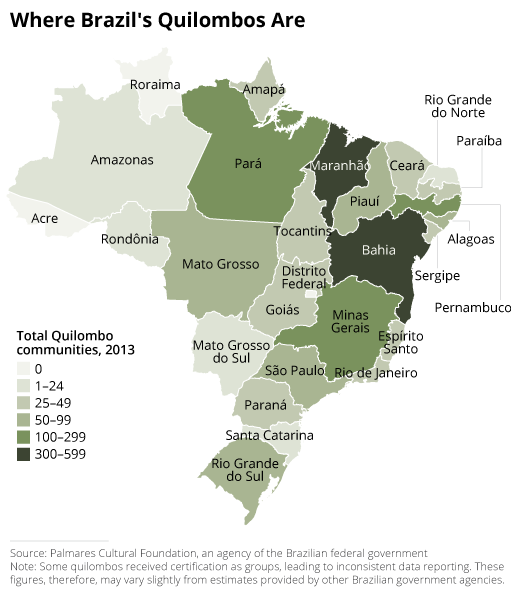

Since Lula’s order, the number of certified quilombos has skyrocketed from fewer than three dozen to more than 2,400, with hundreds more in the process of applying for recognition. In total, more than 1 million Brazilians are demanding their constitutional right to land in what may become the largest slavery reparations program ever attempted.

从卢拉宣布以来,巴西全国“歌伦波”的数量从30个出头猛增到2400个,还有几百个仍然在认证过程中,可以说总计有一百万的巴西人想要在这个历史上最大的奴隶补偿计划中分一杯羹。

In practice, however, the program remains a dead letter for many. Despite a constitutional guarantee and the lip service of almost 12 years of continuous Worker Party-led government, only 217 quilombos have received official land titles as of this year.

而事实上,这个法令对于这其中的大部分人来说仍然是虚设的,虽然有宪法保障,经过长达12年的工党执政之后,只有217个“歌伦波”真正拥有了自己的土地。

Impatient with the slow hand of Brazilian bureacracy, quilombos across the country like Barra do Parateca are invading the promised parcels of land, sometimes igniting violent conflicts with their wealthier neighbors in the process.

而像Barra do Parateca村的这些对政府官僚失去耐心了的人,就开始主动“入侵”这些应许给他们的土地,在这个过程中和他们富有的邻居甚至发生了暴力冲突。

This photo, taken July 5, 2010, shows the ruins of the quilombo association’s makeshift shelter, which the police destroyed weeks before. (Roque Planas/The Huffington Post)

2010年7月拍摄的这张照片就是数周前“歌伦波”的窝棚被警察摧毁后的景象。

Few who walk the lone paved street of the town of Barra do Parateca would imagine that Brazil boasts the world’s seventh-largest economy.

在Barra do Parateca的小道上行走的人可以想象这些年来巴西是如何膨胀到世界第七大经济体的。

Lying off the banks of the São Francisco river, about 400 miles into the rain-starved interior of the state of Bahia, Barra do Parateca is reachable only by boat or by a bumpy ride along a dirt road. Braying donkeys wander freely, feeding on discarded cartons, plastic soda bottles and spoiled food that lies in piles on the ground because the town lacks regular trash collection.

在圣佛朗西斯科河河岸上,深入干旱的巴伊亚省中心600多公里,你只能通过小船和一条颠簸的土路到达Barra do Parateca,南美野驴在路上乱跑,以破烂的纸板箱,塑料可乐瓶和地上的食物残渣为食,因为这个村庄并没有什么垃圾处理设施。

The garbage embarrasses Pereira. An evangelical pastor, he’s thrown himself into building Barra do Parateca’s quilombo with the civic-minded, can-do attitude of a budding politician. (He did, in fact, run for local office recently and lost to a white man, which he said was a bitter experience for an Afro-Brazilian running in a majority-black district.) He wears pressed pants and button-down shirts, drinks soda instead of beer and wants future generations of Barra do Parateca’s students to speak grammatically correct Portuguese, rather than the local dialects that often disregard subject-verb agreement.

福音派牧师Pereira站在这些垃圾中,他是抱着热心公益,开拓进取的念头开始参加当地竞选的。(事实上他刚刚在竞选中输给了一个白人,而他并不是很能接受作为一个非裔巴西人在一个大部分是黑人的地区输掉这一点。)他穿着紧身裤和带袖扣的衬衫,喝的是可乐而不是啤酒,希望Barra do Parateca的下一代能说语法正确的葡萄牙语,而不是现在这样缺少主语的土话。

But building a better Barra is a job that would try the patience of even the most progressive-minded idealist. While the boost in social spending during Brazil’s past decade has helped alleviate the worst of the poverty, few people in town own land or any other productive enterprise that could lift Barra do Parateca into prosperity. Those who do have no intention of handing it over to people like Pereira.

但是建设一个更好的村庄对于这些激进人士来说也是需要耐心的。在过去的十年里巴西大幅增加公共开支缓解了赤贫地区的状况,少部分有土地和生产资料的人可以从中获益,并且让Barra do Parateca变得繁荣么?他们显然并不想让Pereira这样的人也从中沾光。

Facing a life of toiling in someone else’s field for a pittance or waiting to cash government social assistance checks, many residents instead choose to leave. In search of work, they head to cities like São Paulo, a metropolis of 20 million located 850 miles to the south.

要么耕种着别人的土地,等着地主的一点施舍;要么等待着政府的援助津贴支票,这种现状逼得很多人选择离开,到比如说圣保罗这样的有两千万人口大城市讨生活,即使那里远在南方1300公里之外。

Most of them wind up in “favelas,” the violence-plagued slums that ring Brazil’s cities. Others migrate to the interior of São Paulo state to pick oranges or cut sugar cane. In a town of roughly 1,500 residents, some 30 of Barra do Parateca’s men left to work in São Paulo last year, all of them fathers, Pereira says. Another 15 told him of plans to leave this year.

他们中的大多数进入了贫民窟,那是在巴西的城市中治安最混乱的地方,其余一些进入了圣保罗州的内地,在那里采摘柑橘和割甘蔗,在圣保罗一个有1500人的镇子里就有30个来自Barra do Parateca的男人,据Pereira说都是有家室的人,还有十五个这样的人告诉过他想追随他们的脚步。

Despite the hardship, Pereira doesn’t want to leave the place where he was born. He wants Barra do Parateca to break out of its rut. And he sees land ownership, and the independence that comes with it, as the key.

尽管生活这样艰难,Pereira仍然不愿意离开这个他出身个地方,他希望Barra do Parateca能发生改变,而且是从他们获得土地,得到独立开始。

By “land,” he’s quick to clarify, he means real land — not the tiny patch that his neighbors begrudgingly let his quilombo use now. With land, Pereira says, he and his fellowquilombolas could produce their own food, with a little left over for sale in local markets.

“真正的土地”,他又强调了一遍,而不是像现在这样由地主施舍给他的“歌伦波”的豆腐块大小。他说等到有了土地,他和他的“歌伦波”人就能自己种粮食,还能拿到当地市场上去卖。

“We don’t want to keep depending on the government,” Pereira said. “In Brazil, without land, you’re no one.”

“我们并不想依赖政府,” Pereira说。“在巴西,只有有了土地,你才是个人。”

A donkey feeds on garbage tossed along the roads of Barra do Parateca, which lacks regular trash collection. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

一头驴在Barra do Parateca的垃圾堆中觅食。

Brazil is among the world’s most violent countries, with a homicide rate of 25 per 100,000 residents as of 2012.

巴西是世界上最不安全的国家之一,2012年的凶杀率是10万人中有25人。(约世界倒数第二十名)

A government report released last year suggested the persistent killings stem from a “culture of violence” fed by murderous conflicts between the drug cartels and other criminal gangs that have thrived in the cities’ favelas. In the northern city of Maceió, the homicide rate in 2011 stood at a whopping 111 per 100,000, according to the report.

去年的一份政府报告中指出,持续高企的意外死亡数字源于贫民窟中贩毒组织和黑帮带来的“暴力文化”。根据报道,在北部城市马塞纳,2011年甚至在10万人中就有111名死于谋杀。

But Brazil’s overflowing favelas are a symptom of larger problems that originate in places like Barra do Parateca, where waves of impoverished farmers, many if not most of them descended from slaves, have fled the countryside over the past half century. In 1950, the Brazilian census placed the urban population at 31 percent. As of 2013, that figure hasclimbed to 85 percent.

然而巴西贫民窟的扩张的背后有一个更严重的问题,就是从Barra do Parateca这样的村庄流出大量的贫困人口,他们基本都是黑奴的后裔,迁徙到了城市中。在1950年根据巴西的人口普查,城市率是31%,而在2013年,这个数字暴增到了85%。

Land is the one major factor that pushes Brazilians to leave the countryside and crowd into the packed cities. Like in Barra do Parateca, land is all but unobtainable with the wages most Brazilian farm workers make.

土地问题是让这些人背井离乡,挤入城市的主要原因。像Barra do Parateca那样,大部分的巴西农民根本得不到自己的土地。

“The highly unequal distribution of land in Brazil is clearly an important reason that Brazil’s cities have grown in such a rapid, unequal and violent way,” Sean Mitchell, an anthropology professor at Rutgers University who studies quilombos, wrote in an email to HuffPost. While Mitchell thinks it would be “impossible to roll back the haphazard and violent growth of Brazil’s cities through reforms in the countryside,” he added that “land reform would significantly alleviate violence in the countryside.”

“巴西城市凶暴而迅速的扩张造成了严重的土地兼并问题,”罗格斯大学研究“歌伦波”的人类学教授Sean Mitchell在给我们的一封邮件中这样说。他认为这种城市扩张带来的危险和暴力是无法通过农村土地改革避免的,但是他还说了这样一句话“然而土地改革却可以有效减少农村的暴力问题。”

Land seemed an impossible dream for Pereira until 2005, when he helped found a local organization dedicated to addressing racial inequality. While working with the group, he learned about the Brazilian Constitution’s quilombo clause: that communities descended from runaway slaves were entitled to own the land they lived on. All he had to do to gain access to the land was form an official association, collect signatures from a majority of the town’s residents and take them to the country’s capital, Brasília, to apply.

在2005年之前拥有土地对于Pereira来说都是一个遥不可及的梦想,那时他参与了一个旨在解决种族不平等问题的当地组织。正式在那段时间里他才读到了巴西宪法中关于“歌伦波”的条款:逃奴的后代可以拥有他们脚下的土地,只需要他们结成一个官方组织,收集当地大部分居民的签名,然后到首都巴西利亚申请。

Pereira searched Barra do Parateca’s history for evidence of its origins as a quilombo. Very little has been written about the tiny town, but he managed to find an account by a priest, published in 1991, that described the area’s origins as a “fazenda,” or ranch, owned by a Portuguese family during the colonial period. According to the document, the family raised sugar cane and herded cattle using slave labor.

Pereira查阅了Barra do Parateca的历史,想要找到使他们成为“歌伦波”的证据,虽然这个小镇的历史就那么一点,他还是从1991年一个牧师留下的记录中找到了这个地方的起源,殖民时期这里是一个庄园,属于一个葡萄牙人家庭,他们在这里种植甘蔗和放牛,使用黑奴作为劳动力。

“Those were my ancestors,” Pereira said. “It was from that moment that we began to identify, we began to understand our origins.”

“那就是我的祖先,” Pereira说,“那时候我们才觉悟了,我们开始寻找自己的根。”

He gathered signatures from more than half the town’s residents and took the day-long bus ride to Brasilia to drop off the paperwork. The town became a certified quilombo in January 2006, and along with its status came a new school and health clinic.

他收集了这个镇子过半人数的签名,坐了一天的长途车才到了巴西利亚,签署文件之后这里在2006年一月正式变成了一个“歌伦波”,而且获准开办一个新学校和新诊所。

But quilombo certification only extends to the town itself. The coveted farmlands that surround Barra do Parateca remain the private property of assorted ranchers and farmers.

但是这个认证只停留在纸面上,他们所垂涎的环绕在Barra do Parateca四周的土地属于私人,都是各种农场主和牧场主。

And eight years after certification, the government has yet to publish the legally required technical study documenting Barra do Parateca’s land claim, let alone negotiate indemnization with all the current landowners or transfer a title to Pereira and his community.

直到认证了八年之后,政府才又签署了法令支持他们对土地的诉求,然而既没有和原来的地主谈土地赔偿问题,又没有正式把土地产权转移给他们。

Representatives from the Institute of Colonization and Land Reform, or INCRA, which carries out the titling process, say they’re overburdened by the massive number of claims, which as of this year have reached 569 in the state of Bahia alone, according to federal government figures.

殖民和土地改革部(缩写INCRA)的人士说,因为申请的人数实在太多,这个土地转移的问题早就让他们不堪重负了。在巴伊亚一个省他们一年里就要处理569个类似的案例

Although the constitution guarantees quilombos’ property rights, INCRA can’t simply take chunks of land and hand them to new owners. Instead, it must compensate the titleholders, who generally resist the agency’s attempts to take over their property, leading to lengthy legal disputes.

即使宪法给了“歌伦波”合法权利,INCRA也不能直接把一块块土地直接送到新主人手上。他们必须向正在为了自己原来拥有的土地和政府进行漫长诉讼的地主们进行赔偿。

“We can’t expropriate land — we also have to indemnify,” Itamar Rangel at the INCRA’s office in Salvador da Bahia told HuffPost. “Brazilian law defends the property rights of any citizen.”

“我们没有权利直接征收土地,我们当然得对他们进行赔偿,” Itamar Rangel在巴伊亚省萨尔瓦多市的INCRA办公室里对我们说。“巴西法律当然要维护个人的物权。”

That lack of efficiency isn’t unique to the state of Bahia. INCRA estimates the total amount of land currently claimed by quilombos in Brazil to be around 4.4 million acres — an area roughly the size of New Jersey.

巴伊亚省的情况当然也不是独有的,INCRA统计整个巴西的“歌伦波”需要划出440万亩的土地,差不多等于新泽西州的大小(比整个北京市略大)。

巴西的“歌伦波”的增长

But the government has issued just 217 land titles as of this year, having granted only three last year and three in 2012. At this rate, the growing backlog that now stands at roughly 2,200 quilombos won’t be getting cleared any time soon.

但是到今年(2014)为止政府只给了217个“歌伦波”合法的土地产权,在2013和2012年都只批准了三个,按这个速度继续下去差不多有2200个“歌伦波”是永远别想完成这个目标了。

In 2007, frustrated with the pace of Brazilian bureaucracy, Barra do Parateca’s quilombo association stopped waiting and started planting. They planted along the river banks. They planted on land just outside the town. They rode boats up the river and walked into the forest to plant in isolated fields, setting up campsites along the way. Today, when the quilombo residents are able to harvest those crops, it helps supplement their modestly stocked pantries and refrigerators.

在2007年,无法忍受巴西官僚的磨洋工的Barra do Parateca人决定团结起来,放弃等待。他们开始在河岸上耕作,就在镇子外面耕作,他们乘船进入森林开辟小块耕地,沿路建立定居点。现在这些作物可以收获了,填满了他们的储藏室和冰箱。

The landowners usually fight back. As often as not, landowners find the clandestine fields and let cattle loose to feed on the crops before they’re harvested.

这时候地主开始反击了,找到森林里的那些小块耕地之后,他们把牛赶进地里,在收获之前吃掉作物。

About a dozen landowners from Barra do Parateca are battling the quilombo association’s claims. Of all those fights, none is more tense than the one involving the Pinto family.

有十几家地主都在反对“歌伦波”的入侵,这其中态度最激烈的应该就是Pinto家族。

Hélio Pereira Pinto, 71, isn’t the kind of person you’d imagine as one of the quilombo’s biggest enemies. An aging man whose thick, sun-battered skin folds neatly along his cheeks, Pinto walks with a limp, the result of his father’s inability to pay for a doctor when Pinto developed a benign tumor in his left knee at age 10.

“歌伦波”的头号敌人Hélio Pereira Pinto今年已经71岁了,然而他面颊上厚厚的饱经日晒的皮肤还蛮紧致。Pinto只有一条腿,因为在他十岁的时候他的父亲付不起为他做骨肉瘤手术的钱。

Although the tumor splintered his tibia, forcing shards of bone through his skin, he spent his life working as a field hand, one of the most backbreaking and poorly paid jobs Brazil has to offer. He still has scars under his arm from the years he worked in the fields while supporting himself with a crutch. He remembers listening to radio broadcasts from Cuba’s Communist government in the 1960s, hoping that a similar revolution would make its way to Brazil. But his experiences in recent years have tempered his revolutionary enthusiasm.

尽管肿瘤扭曲过他的胫骨,把骨头碎片挤出肉来,他仍然把一生都花费在田地里,这在巴西是最苦,回报最少的工作。他的胳膊下面还留着当年拄着拐杖在地里劳作时磨出的伤疤。在1960年代他曾经听着古巴革命武装力量的广播,盼着这样的革命在巴西也上演一次。但是这几年来的经历让他的“革命热情”减退了。

Pinto owns the piece of land where Pereira and his fellow quilombolas have arrived at their uneasy truce. His son João Batista Pinto — a judge in the neighboring city of Guanambi who is entangled in a separate land dispute with the quilombo — has repeatedly called the cops to kick them out.

在Pereira和他的“歌伦波”人终于得到承认之后,他们恰好就站在了Pinto的土地上面。他的儿子João Batista Pinto在旁边的城市瓜南比担任法官,在一场“歌伦波”的土地争夺案件中,他的决定是让警察把他们都赶走。

After the police destroyed the quilombo association’s illicit crops in 2010, someone set a bus belonging to Hélio Pinto on fire. The Pinto family suspects retribution, but no one has owned up to the deed. Four years later, the bus’s charred remains still sit on the town’s main road, now engulfed by a tree that has grown around it.

2010年在警察夷平了“歌伦波”的农作物之后,一些人烧掉了Pinto拥有的一辆客车,Pinto家族认为这是一种报复,但是并没有找到人来对此负责,四年之后烧焦的残骸仍然横在路上,从中长出了一棵树。

Land holds much the same meaning for Hélio Pinto, who is white, as it does for Pereira. The oldest of 18 children, Pinto was born less than two miles from Barra do Parateca, where his landless family lived on the property of a wealthier man named Antonio Bastos. Pinto’s family worked as “agregados,” meaning they were allowed to live on the land and use a chunk of it to grow their own food, in exchange for their labor. Some experts have described the relationship, common in the Brazilian countryside, as something better than slavery, but not quite freedom.

对于Hélio Pinto来说土地的意义也是很重要的,虽然他和Pereira不一样,他是个白人,是十八个兄弟姐妹里的老大。Pinto出生的地方离Barra do Parateca有3公里,那时他全家都住在一个更有钱的叫做Antonio Bastos的人的土地上,他们当时是佃农,就是说他们自己的土地上耕作,而只有一部分农作物属于他们自己,根据研究,在巴西的农村这种生产关系是更普遍的,它比奴隶制更好,尽管也剥夺了一部分人的自由。

One day, for reasons unclear to Pinto, Bastos kicked the family out, along with his other agregados. Pinto’s father found new work as an agregado on a ranch in what would become Barra do Parateca. This was in the early 1950s, and Barra wasn’t yet a town — just another tract of land owned by a wealthy ranching family. After decades of working the fields, Pinto scraped together enough money to buy the small patch of land that the quilombo association now disputes.

终于有一天不知为了什么原因,Bastos把他们和其他佃农一起踢出了那片土地,于是Pinto的父亲来到了Barra do Parateca继续当佃农,那是1950年代早期,当时这里并不能被称作是一个镇,而只是一个大牧场主拥有的一片土地。经过几十年的耕作,Pinto家族攒够了足够的钱买下了这片不大的土地,正是“歌伦波”想要得到的这一块。

The fighting has grown so frustrating for João Batista Pinto, Hélio’s son, that he doesn’t even want his parcel of land anymore. As a lawyer in the neighboring city of Guanambi, he now has little use for it, and the bad blood created by the land conflicts makes him feel uncomfortable visiting the town of his birth. He would gladly give it up, he says, if only someone would pay him for it.

对于Pinto的儿子João Batista Pinto来说这场冲突已经让他受够了,他也在瓜南比担任律师,他甚至想到要放弃。土地冲突中那些人的恶意让他甚至不想回到这个他出生的小镇,如果有人想买,他会很干脆地把这片土地卖掉。

It’s not the first time someone has tried to take over João Batista Pinto’s small patch of land. In the 1970s, when Brazil was under military rule, the Bahian government unsuccessfully tried to relocate the town to accommodate a dam project. The INCRA expropriated a series of tracts in the area, including João Batista’s. So the land, in theory, belongs to the government — except that, as often happens with Brazil’s slow-moving bureaucracy, INCRA never paid him for it.

这不是第一次有人想获取这片土地了,在军政府执政的1970年代,巴伊亚省政府就想为了一个水坝工程把这个镇迁走。INCRA征收了一部分土地,包括属于João Batista的那部分。所以说理论上这片土地是属于政府的,但是就像经常发生的那样,由于巴西官僚地低效率,INCRA到现在也没有付过钱。

“This case has been pending ever since then, until the present day,” João Batista said. “Without payment, without indemnization. This happens all over the place in Brazil.”

“从那时起这个计划就被搁置,直到今天,” João Batista Pinto说。“没有拨款也没有赔偿,在巴西其实这种状况很普遍。”

Still, Hélio Pinto has trouble understanding how Barra do Parateca could possibly be a quilombo. As one of the few residents who’s lived in the town since its establishment, he knows that the original inhabitants were, like him, virtually all white. Now, he says, the peaceful community he once knew has been torn apart, and the land he labored for has been made worthless by the political aspirations of black people from neighboring towns.

现在Hélio Pinto仍然对于Barra do Parateca变成了一个“歌伦波”感到迷惑不解。作为从这个镇建立以来就住在这里的少数元老之一,他知道这里的第一批居民基本都是白人。他说这片土地上的宁静已经被这些从附近涌来的黑人邻居打破了。

“There was never any quilombo here. There were never any slaves,” Pinto said. “Today most people here are black, there’s no white people anymore. But the blacks are all migrants. None of them are really from here.”

“这里根本就没有过什么‘歌伦波’,也没有过什么奴隶,”Pinto说。“现在这里全是黑人,几乎看不见白人了,但是这些黑人全是外来者,根本不是在这里出生的。”

The main street of the town of Barra do Parateca, Brazil. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

Barra do Parateca的主干道

Many in the Brazilian media share the Pintos’ suspicions about the authenticity of today’s quilombos. Television coverage often tilts more toward his point of view than Pereira’s.

许多巴西国内媒体转载了Pinto对于“歌伦波”真实性的怀疑。电视节目里也更倾向他的观点,而不是Pereira的。

One of the most famous cases occurred in 2007, when Brazil’s largest television news broadcaster, O Globo, visited the quilombo of São Francisco do Paraguaçú in the northern part of the country. O Globo’s reporters asked residents if they considered themselves quilombolas. Several people said no. One man said he’d never heard of the term until recent years. Another said he’d never heard the term at all.

在2007年就发生了这么一个着名事件,巴西最大的电视新闻台O Globo采访了圣佛兰西斯科和帕拉瓜的“歌伦波”。记者访问当地居民时问他们是否认为自己是“歌伦波”人,有几个人给予了否定回答,有人说直到近几年才听说这个说法,甚至有人根本对此闻所未闻。

In the final version of the story, the producers did not air the comments of the quilombo association’s leaders or the interviewees who affirmed the existence of their quilombo. The story erroneously claimed that the area was not a historical site of slavery and that sugar had not been planted in the region when, in fact, the ruins of a colonial-era sugar mill lay just a short distance upriver.

而在采访的最后,制作者并没有采用“歌伦波”的领导者在采访中对于“歌伦波”存在的解释,而是犯了个错误,声称这个地方在历史上就并没有蓄过奴,而这个地区种植甘蔗的历史是从殖民时期结束之后才开始的。

The report sparked protests in the community and deepened a rift that pitted neighbor against neighbor, with some residents posting signs in front of their doors reading “I’m not a quilombola, no.” The federal government re-uated the community’s anthropological report, but it eventually chose to uphold the group’s quilombo certification.

这个采访节目引起了当地的抗议,加剧了不同阶级之间的矛盾,有些居民在自己的屋门前竖起了牌子,写着“我不是‘歌伦波’人,不!”。联邦政府重新对这个地方是不是“歌伦波”进行了调研,但是最后的结果还是维持原判。

Despite the support of the government, episodes like this have undermined the public image of the fledgling social movement. Politicians who would go on to form Democráticos 25, a conservative, pro-market political party, hoped to take advantage of public doubts about quilombos’ credibility. They filed a legal challenge in 2004, arguing that Lula da Silva’s decree allowing virtually any group of black people to declare themselves a quilombo illegally skirted Congress’ authority.

如果没有政府的支持,这个小插曲可能就已经毁掉了这个新生社会运动在民众心中的声誉。一些民主党的政治家想要推进公众对“歌伦波”可信性的质疑,他们的政治倾向是保守,偏向自由市场的。在2004年他们就已经在国会提交了对于卢拉法令的不信任案,认为这种把所有黑人统统划为“歌伦波”人的做法损害了国会的执政基础。

By 2010, the case had made its way to Brazil’s highest court, which has yet to rule on it. A decision in Democráticos 25’s favor could annul all the land titles issued under the law and strip thousands of communities of their quilombo status overnight.

到了2010年,这个事件闹到了巴西的最高法院,至今法院的决定是收回这些土地的产权,一夜之间剥夺了数千个“歌伦波”社区的合法地位。

Pereira doesn’t dispute that Barra do Parateca was once a largely white community. He acknowledges that most of the town’s black residents first arrived about four decades ago — including his mother, who was born in a town on the other side of the river.

Pereira并不否认Barra do Parateca从前曾经全是白人,他认为黑人们是在40多年前就来到了这里,其中就有在河岸另一边的镇上出生的他的母亲。

But he also takes a wider view of his community’s history. According to the priest’s 1991 account, before the town existed, the area of Barra do Parateca belonged to one large Portuguese landowner whose massive holdings stretched across the hinterland. That man’s claim encompassed a number of neighboring majority-black towns, including the first certified quilombo in the state of Bahia, Rio das Rãs.

但是他把目光放远的时候,发现在那个牧师在1991年留下的记录中写到,在Barra do Parateca建立之前,这里属于一个更大的葡萄牙地主,几乎拥有这整片荒凉的地区,在这之上发展起了好几个由黑人组成的镇子,其中就包括巴伊亚省第一个承认的“歌伦波”,Rio das Rãs。

“Before the community, before the town, it was a fazenda,” Pereira said. “So all of this black population here in the Parateca region — Pau D’Arco, Barra do Parateca — in reality, we’re all the same people.”

“在这里住上人,形成村镇之前,这里全是农场,”Pereira说,“所以整个Parateca地区,不管是Pau D’Arco还是 Barra do Parateca,事实上,全都属于我们。”

And anyway, all of this is beside the point, as far as Pereira is concerned. Fighting over these chunks of land for the last few years has made him rethink not just poverty, but race as well.

尽管如此,尽管他还是持这样的观点,这么多年的斗争让Pereira开始反思更多关于贫穷和种族的问题。

“Slavery was abolished,” Pereira said. “But the black people around here — my ancestors — never had a single title. Abolition happened, but we’re practically continuing as if we were slaves today. How come we don’t get the right to reparations?”

“奴隶制被废除了,”Pereira说,“但是这里的黑人。我的祖先并没有得到什么真正的好处,就算废除了奴隶制他们还是在土地上过着奴隶的生活,我们怎么可能不要求更多的赔偿?”

The charred remains of a bus set ablaze in 2010 remain standing on the main street of Barra do Parateca, Brazil. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

那个被焚毁的客车。

Brazilians’ disagreement over how to define a quilombo stems in part from thecountry’s historic reluctance to define who is black. People either partially or wholly of African descent make up a majority of the population, but unlike in the United States, Brazil never saw widespread legal segregation, and racial mixing has been common since the colonial period.

巴西对于“歌伦波”地位的争论也源于对历史上对黑人这个定义的界定产生的问题。这个国家的大部分人都是或多或少有非洲血统,但是和美国不一样,巴西从来没有大规模的种族隔离,从殖民时代开始种族融合就一直在进行。

That legacy has made it difficult for Brazilians to build political movements devoted to confronting racism. Many Brazilians view their country as a “racial democracy,” where the lack of strict distinctions between “black” and “white” has fostered an ethnically harmonious society.

这个遗留问题使得巴西很难直接对种族歧视问题发起政治运动。很多巴西人把自己的国家视为多种族共和国的典范,对“黑”和“白”模糊的定义造就了在人种之间达到和谐的社会。

Yet Afro-Brazilian intellectuals and the country’s social scientists have long dismissed that interpretation, pointing to research and statistics that they say reveal broad patterns of discrimination.

但是有文化的非裔巴西人和社会学家却想把这个状况打破,想通过研究和统计把种族之间的差异搞清楚。

As of 2011, Brazilian black and mixed-race workers on average earned only 60 percent of the salaries of white workers, according to the country’s national statistics agency. Some70 percent of homicide victims are black, according to a 2013 study by the Institute of Applied Economic Research. Researchers at the Federal University of Rio de Janeirocalculated last year that if the Brazilian population were divided along racial lines, whites would occupy the 65th position on the U.N. Human Development Index, while Afro-Brazilians would only reach 102nd place.

在2011年,根据国家统计局的数据,巴西的黑色和混血职工的平均工资等于白人职工的60%。70%的自杀人口是黑人,而在2013年里约热内卢联邦大学的实用经济学调查中如果把巴西的人口按照种族划分开,在世界人类发展指数排名上,白人可以排到第65位,而黑人要排到102位。

Given the expansiveness of Brazil’s legal definition of “quilombos,” it’s hard to mount an argument that Barra do Parateca does not qualify. More than half of the Barra do Parateca community signed the petition to declare its ethnic quilombo identity, as required. A social scientist visited the town and verified the claim.

“歌伦波”的定义是很宽泛的,很难确定Barra do Parateca到底合不合格,这里的居民有一半签了字支持这个申请,于是一个社会学家到这里来考察他们说词的真实性。

The lawsuits filed against the quilombo’s land invasions would, theoretically, be trumped by a decision by INCRA to compensate the current landowners accordingly and seize the property on behalf of the quilombo.

这个关于“歌伦波”侵占土地的法律诉讼,理论上最终将取决于INCRA是否作出一个决定,就是他们将赔偿原先的土地拥有者,进一步使“歌伦波”拿到土地的产权。

But INCRA’s officials, 500 miles away in a building with a leaky ceiling, have yet to finalize the paperwork, let alone issue a land title. They’re responsible for the nearly 600 quilombo claims across Bahia, some of which face crises more serious than Barra do Parateca’s.

但是在800公里之外的一座有镂空天花板的建筑里,纸面上的工作仍然没有完成,更不要说土地产权的问题。在巴伊亚省他们就要面对接近600个“歌伦波”的问题,其中一些面临的问题比Barra do Parateca的更严重。

Nevertheless, the lack of progress infuriates the already frustrated quilombo association. When asked who the quilombo movement’s greatest enemy is, Pereira didn’t mention the landowners. Instead, he began talking about the government, which catapulted the movement into existence in 1988, then let it founder, leaving quilombo residents to wonder whether the constitutional article will wither into a broken promise.

于是现在这种并没有什么进展的现状激怒了那些饱受煎熬的“歌伦波”组织。如果问他们“歌伦波”运动最大的敌人是谁,Pereira这样的人不会说是地主,而是将矛头指向政府。政府在1988年突然开始了这个运动,之后放任它走向衰败,让“歌伦波”居民们把宪法里的那些条文只能看成空头支票。

“The greatest enemy of the quilombo movement is the Brazilian state itself,” Pereira said. “The slowness.”

Pereira说:“‘歌伦波’最大的敌人就是懒惰无能的巴西政府。”

Almir Viera Pereira seated in his mother’s kitchen in the town of Barra do Parateca, Brazil. (Carolina Ramirez/The Huffington Post)

João Batista Pinto’s anger at the quilombo association is no longer what it was four years ago, when he sent the cops to break up its occupation of his land. He’s now resigned to put up with the irritation of the land dispute while the courts and INCRA slowly sort the mess out.

João Batista Pinto对于“歌伦波”组织的愤怒已经不像四年前他把警察送去逮捕那些占领他土地的人时那么强烈了。他现在已经退休了,旁观着这场连法院和INCRA都纠缠其中的纠纷。

But like his father, he harbors resentment, and finds it laughable to think Barra do Parateca could be classified as a quilombo.

像他的父亲一样,他不再在乎憎恨,把Barra do Parateca的“歌伦波”运动只看成一件好笑的事。

“It’s an old concept,” João Batista said. “To apply it to the contemporary world is difficult. They’re trying to apply that article in order to gain social benefits, but they’re doing it fraudulently.”

“这只是一个旧观念,”Pinto说。“他们倒不合时宜地想硬把它融入现实,来向这个社会攫取利益,这本来就是一种欺骗手段。”

Recalling the old problem of how to define who is black in Brazil, João Batista pointed out that his sister Heldina looks white, and then asked rhetorically if he himself looks black. With his dark bronze skin and coarse straight hair, he could belong to any number of Brazil’s intermingling ethnic combinations. In the United States, no one would call him white. João Batista added that he and his family come from Barra do Parateca. Does that make them quilombolas?

回到那个“什么样的人是真正的黑人”的老问题上,Pinto说他的妹妹Heldina看起来完全是白人,然后问我们觉得他自己看起来像不像黑人,从他深棕色的皮肤和蓬松的直发看来,他可能属于巴西任何一个混血种族之一。在美国没有人会说他是白人。他还说:“我和我的家族也是在Barra do Parateca出生的,我们也应该是‘歌伦波’的一分子咯。”

“It’s not enough just to demonstrate the presence of a black population, because if that were all you needed, Salvador da Bahia would be a quilombo,” he said. “Bom Jesús da Lapa, Rio de Janeiro, all the other states. Brazil would be one giant quilombo.”

“只是把黑人这个概念简单地定义出来是不行的,因为如果有需要的话,萨尔瓦多市整个都可以是一个‘歌伦波’,”他说。“还有里约热内卢和其他的地方,整个巴西都是一个‘歌伦波’。”

In the meantime, Barra do Parateca waits, and Pereira enjoys his early morning walk around the roça while a friend hacks at weeds with a machete. The soil might be more moist if Hélio Pinto hadn’t taken down the irrigation system he installed years ago. On the other hand, the cops haven’t come this year to kick the quilombo out and destroy the small patch of plantings on the Pinto family’s 15-acre plot.

视线转向Pereira,他正在田里享受着早上的散步,一个朋友正在用弯刀除去野草,如果几年前Hélio Pinto没有毁掉他的灌溉设施,这土地本来应该更湿润一些。从另一个角度来说,今年警察并没有像往常一样来把这片属于Pinto的十五亩土地上的“歌伦波”铲平。

In his mother’s kitchen, Pereira sits down to eat a cut of gristly beef with a side of rice, black beans and farofa, a yucca flour that Brazilians sprinkle on their food to add flavor and make it more filling. For Pereira, few things reveal more about Brazil’s race relations than his meals.

在他母亲的厨房里,Pereira吃着一份带软骨的牛肉,加上米饭黑豆和薯粉,上面洒着巴西人喜欢用的调料,一种丝兰的粉末。对于Pereira来说,吃饭问题比种族问题更重要。

“This is the way I see it, the world is what you’re thinking about,” said Pereira. “If you’re hungry, what are you going to think about? About food. So most of the world’s poor only think about food. They go to school and they’re thinking about snack time, about lunch, because those who are hungry only think about eating.”

“我的观点是,我思则我在,”Pereira说。“但是如果你饿了,你会想到什么?当然只有吃的,所以世界上的穷人全是为了吃的而活着的。他们就算上学也想着吃零食,吃午饭,因为穷人只是想填饱肚子而已。”

Pereira said he envies the United States, a country viewed by many Brazilians as more racist than their own, for electing a black president. Why, he asks, in his country, where people of color make up a majority of the population, does the idea of a black president seem beyond the realm of possibility? Like most quilombolas, Pereira isn’t convinced that he lives in a racial democracy.

Pereira说他嫉妒美国人,即使就算在巴西人看来美国的种族分裂也更严重,但是他们选出了一个黑人总统。那么巴西这么一个黑人占绝大多数的国家, 选出一个黑人总统还会远么?像大多数“歌伦波”人一样,Pereira并不觉得巴西是一个多种族融合的好例子。

“They say it’s not, but Brazil is a racist country — in all the ways that you could imagine,” Pereira said, pointing to the skin on his forearm. “In Brazil, poverty has a color.”

“只有‘他们’说巴西并不是一个种族主义化的国家,不管你怎么想,”Pereira说,指着他手上的皮肤。

“在巴西,贫穷就是我的种族。”

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10