[ 美国 国家地理 ] 为什么俄罗斯年轻人都视普京为英雄 (文长图多,爪机慎入) [美国媒体]

苏联解体25年后,他们希望能有一个坚毅的民主主义总统。普京的影响力普京被公认为是解体后苏联的驾奴者,是几十年来第一位敢于与西方对抗的领导人。他个性坚毅,绝对掌控俄罗斯媒体,始终立于不败之地,尤其是在年轻人的心中。如果在2018年再次当选,他可能是当选领导人时间最长的人,仅次于有30年统治的斯大林。

Why Many Young Russians See a Hero in Putin

为什么俄罗斯年轻人都视普京为英雄

Twenty-five years after the breakup of theSoviet Union, they crave the stability that the nationalist presidentrepresents.

苏联解体25年后,他们希望能有一个坚毅的民主主义总统

Kirill Vselensky perches on a cornice in Moscow as Dima Balashov getsthe shot. The 24-year-olds, risktakersknown as rooftoppers,celebrate their feats on Instagram: @kirbase and @balashovenator.

莫斯科,Dima Balashov举着相机正为站在屋檐一角24岁的Kirill Vselensky拍照。这位“冒险家(risktakers)”被称为rooftoppers(飞檐舞者?)。

He doesn’t know where to take me when Imeet him at the hotel by the train station, so we just start to walk down thedusty summer streets of Nizhniy Tagil, a sputtering industrial city on the eastern slope of the Ural Mountains. His name is SashaMakarevich, a 24-year-old cement worker, a blond ponytail falling down hisback, a Confederate flag stitched onto his cutoff denim vest. “I thought itjust meant independence,” he explains when I ask about it.

当我到火车站边的酒店接他的时候,他还不知道在哪找我。当时还是夏天,所以我顺着尘土飞扬的下塔吉尔大街走下去,下塔吉尔是在乌拉尔东坡延伸出的一座工业城市。他名字叫Sasha Makarevich, 24岁的水泥工,背后披落着一条金黄色的马尾辫,身着印有邦联国旗的齐胸牛仔背心。当我问他这是啥意思时,他解释说“我认为这寓意着独立意识”

We walk past a small, one-story cube of abuilding covered with images of red Soviet stars and the orange-and-black St.George’s ribbon that holds imperial, Soviet, and Russian military medals. “Wecould go in here,” Sasha shrugs. “But it’s full of people who survived theNineties.”

我们路过一个,涂有苏维埃红星和橙黑相间圣乔治丝图案,内有苏联帝国和俄国军事奖章的立方型小纪念馆。“我们可以去这里看看,”莎莎耸了耸肩说道。“但这里都是九十年代的人用过的。”

Sasha survived the Nineties too. InDecember 1991, just months before he was born, the Soviet flag came down over theKremlin and the Russian tricolor went up, ushering in the decade that hangslike a bad omen in the contemporary Russian psyche. The expectation thatRussians would start living like their prosperous Western counterparts gave wayto a painful reality: It would be a hard slog to turn a command economy into amarket one, to make a democracy out of a society that had lived under absolutemonarchy and totalitarianism for centuries.

莎莎也是在90年活过来的。一九九一年十二月,他出生的前几个月,苏联国旗在克里姆林宫倒下、随后俄罗斯三色旗升起,在旗帜飘扬的这十年,这代俄罗斯人的心中似乎总萦绕着一种不祥的预感。俄罗斯人也期望能像他们西方发达邻居一样生活,但现实是残酷的:好几个世纪生活在专制集权下的社会民主,把社会主义经济转变成市场经济,这将是一个艰难的过程。

Alexander and VictoriaKhlynin escape the everyday through cosplay(costume play) in their suburban Moscow flat. The 28-year-old banker and25-year-old interior designer own several animal outfits. Many young Russians,shaped by the chaos of the 1990s and conformity of the Vladimir Putin years,seek stable jobs and families.

Alexander 和 Victoria Khlynin 每天都在他们莫斯科郊外不起眼的小区里玩扮装游戏。这位28岁的银行经理和这个25岁的室内设计师自己设计制作了一些动物装饰。由于普京时代混有90年来的纷杂,有不少年轻人的追求是,能有一个稳定的工作和家庭。

The Wild Mint festival, a multiday extravaganza held about a hundred miles outside Moscow,draws more than 36,000 fans who camp out in a tent city to hear bands playuntil 3 a.m. Among this year’s highlights were the Accident, a popular Russianband that sings about old-fashioned values, and the WantonBishops, from Beirut.

在俄罗斯约一百公里外,每年都举行盛大的“野薄荷”节,多日进行狂欢。有三万六千名粉丝被吸引到一个小城市里扎营听乐队演奏,一直持续到凌晨三点。不过今年的表演有些令人意外,有个俄罗斯流行乐队唱了有复古风和“肆意主教”(蓝调摇滚)风格的歌曲。

I never got to see those Nineties. Myfamily left Moscow in April 1990. When I first returned, in 2002, the era ofPresident Vladimir Putin, the antidote to the turbulent Nineties, was in fullswing. Since then I’ve been back to Russia many times and lived there forseveral years as a reporter.

我从未在90年代呆过,我家人在1990年4月就离开了莫斯科。2002年我第一次来到莫斯科。普京统领的时代,正从方方面面平息90年以来的动荡。自从那时起,我多次回到俄罗斯,并成为一名记者在那里住了几年。

Most of the Russians I know have, to someextent, been shaped by the 74-year Soviet experiment. We know in a deep,personal way our families’ small histories and tragedies within the largertragedy of that history. But this generation coming up knows only a Russiatraumatized by the Nineties and then tightly ruled by Putin. This year—25 yearsafter the Soviet Union’s collapse—I went back again, to meet these young peoplelike Sasha. Who are they? What do they want from their lives? What do they wantfor Russia?

从某种程度上来讲,我很了解俄罗斯人,他们已经被74年的苏联洗脑了。我们深刻地感受到,在令人极度伤感的背景下,我们家的历史变迁。可这代人牢牢记住了俄罗斯1990年以来的那段悲伤,于是紧紧跟随着普京。今年,也就是苏联解体后的第25年(BLUEBIT注:估计2015年写的)。我重回莫斯科,来看望像莎莎这样的年轻人。(我想知道)他们是谁?他们想要从他们的生活中得到什么?他们想为俄罗斯做什么?

Inside the windowless bar, all linoleum andfake-wood paneling, Sasha and I get some thin beer in thin plastic cups andfind a seat among the heavily tattooed, red-faced men in tracksuits andsandals, blasting reedy Russian pop from their phones.

在到处都铺着地毯和仿木装饰的无窗酒吧里。莎莎和我拿着盛着啤酒的纤薄塑料杯,瞧见一群几乎纹满全身,身着运动服,脚穿凉鞋,坐在座上散发着满面红光的男人,爆棚似的俄罗斯流行音乐正从他们的手机里喷涌出来。

Nizhniy Tagil, Sasha says, “is all factories and prison camps.” Once famous formanufacturing the Soviet Union’s train cars and tanks, it’s now famous for itsidled factories, unemployment, and Vladimir Putin. When Putin announced, in2011, his intention to return for a third presidential term, protests broke outin Moscow and other large cities. The protesters were largely from the young,educated, urban middle class, and that winter a factory worker from NizhniyTagil told Putin on national TV that he and “the boys” were ready to come toMoscow to beat up the protesters. Putin demurred, but the city has come to beseen as the very heart of Putinland.

“下塔吉尔全是工厂和监狱”,莎莎解释道。这里曾以苏联时期生产火车车厢和坦克而闻名,不过现在这些工厂停产的停产,工人失业的失业,还因普京出了名。 2011年普京曾宣布,他打算再当一届总统,莫斯科等大城市当即爆发了抗议活动。示威者主要来自年轻的,受过教育的城市中产阶级,还有来自下塔吉尔的失业工人,他们上国家电视台向普京表示,他和“孩子们”打算去莫斯科痛殴说这话的人。普京表示反对,但这座城市已被看作“腐败场”(Putinland)的中心。

Supporters of the Other Russia, anopposition party, rally in Moscow, displaying flags and armbands with theirsymbol, a grenade. The Other Russia was formed by members of a bannedultranationalist political party in 2010, but it is not recognized by Putin’sgovernment.

反对党—“另一个俄罗斯”党的支持者在莫斯科集会。该党旗帜和臂章绣有一枚手榴弹。“另一个俄罗斯”党。是2010年由一些极端民族主义成员组成的党派,但普京不承认该党。

At a sports and military camp, paratroopersteach children as young as 10 how to handle weapons. Putin has restored Russianpride in the country’s military might by defeating rebels in Chechnya, seizingCrimea, invading Ukraine, and intervening in Syria. Young people in particularsay they want Russia to be seen as a global power.

在一个军事运动训练营里,伞兵正在教一群10岁大的孩子使用武器。普京已经恢复了俄罗斯的军事荣耀,并打败车臣叛军,占领克里米亚,侵入了乌克兰,还对叙利亚进行干预。年轻人尤其认为,他们希望俄罗斯被视作全球强国。

Now Nizhniy Tagil has a new mayor, whomPutin sent in to beautify the city, and a local magnate has built a fancyhealth care clinic, but life is still tough here. Sasha went to school forwelding and worked in a factory making good money until crashing oil prices andWestern sanctions for the invasion of Ukraine sank the economy. Sasha stoppedgetting paid. He spent a year looking for work before he landed a job in aBoeing factory two hours away. Now he makes 30,000 rubles, or $450, amonth—about the local average.

目前,下塔吉尔有了一位新市长,普京让他去美化城市,市长和当地富豪联合修建了一座挺花哨的医院,但在这里,生活依然艰苦。莎莎去学校学当一名焊工,后来找到了一家工厂工作、还赚了大钱,直到油价下跌崩溃,因入侵乌克兰遭到西方制裁而经济萧条。莎莎失业了,之后她花了一年的时间又去找工作,最后好不容易找到了一份距波音公司工厂有两小时路程的工作。现在他工资为三万卢布,相当于450美元,跟当地的平均水平差不多。

I meet Sasha after a long workday, and heis tired, his hands dirty. He doesn’t feel totally comfortable—or safe—in thisbar with the survivors of the Nineties. The city he describes is a violentlyconformist place. “People here are very aggressive toward anyone who doesn’tlook like them,” he says. It’s a local, working-class uniform: tracksuit, buzzcut with a hint of bangs. His peers, Sasha says, are often children of ex-cons.“They don’t respect the law,” Sasha says. “ ‘A real man is either in the armyor in jail.’ My sixth-grade teacher told us that.” So Sasha learned to fight,with fists, with knives. Once he walked home after a fight covered in someoneelse’s blood, and he is strangely, beatifically cheerful as he tells me allthis.

我遇到了双手脏兮兮、劳累一天的莎莎。在这个酒吧里,和这帮生活过90年代的人坐在一起,不舒服也不安全。他说这座城市是一个平淡有序的地方,这里的人看起来好像很有点进攻性,但不是。这里的工人着装统一,都留着齐刷刷的流海头。莎莎说,跟他差不多大的,基本都有些孩子气。“他们都不怎么守规矩”。一个正常男人不是去当兵就是去蹲监狱。莎莎说道。这些都是我们以前我六年级老师讲的。所以莎莎学会了用拳头,拿刀打架。他曾经给别人打出血后施施然地走回了家,让人不可思议的是,当他跟我说这些事的时候竟然很高兴。

What Sasha really wants to do is escape tocosmopolitan St. Petersburg and open a bar. He’s been there a couple times;it’s where he feels most at home. But his girlfriend won’t move unless he buysan apartment there. Between his salary and hers, his dream will likely remainjust that.

莎莎真正想的是能跑到圣彼得堡这个大都市开个酒吧。他去过那儿有好几次,那里是他最能感到能成为家的地方。但是他的女友不想去,除非他能在那儿买个房。踌躇在钞票和女友之间,开酒吧变成了个梦想。

Popularity,Putin Style Vladimir Putin is widely viewed at home as theman who tamed a tumultuous post--Soviet Russia and the first leader in decadeswilling to stand up to the West. His strong personality, combined withnear-total control over the Russian media, has helped him keep his standing,especially among the young. If reelected in 2018, he’ll be Russia’s secondlongest serving leader, trailing only Joseph Stalin’s 30-year reign.

普京的影响力普京被公认为是解体后苏联的驾奴者,是几十年来第一位敢于与西方对抗的领导人。他个性坚毅,绝对掌控俄罗斯媒体,始终立于不败之地,尤其是在年轻人的心中。如果在2018年再次当选,他可能是当选领导人时间最长的人,仅次于有30年统治的斯大林。

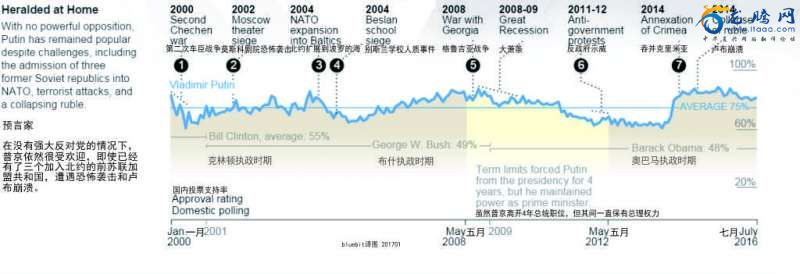

Heralded at Home With no powerfulopposition, Putin has remained popular despite challenges, including theadmission of three former Soviet republics into NATO, terrorist attacks, and acollapsing ruble.

预言家 在没有强大反对党的情况下,普京依然很受欢迎,即使已经有了三个加入北约的前苏联加盟共和国,遭遇恐怖袭击和卢布崩溃。

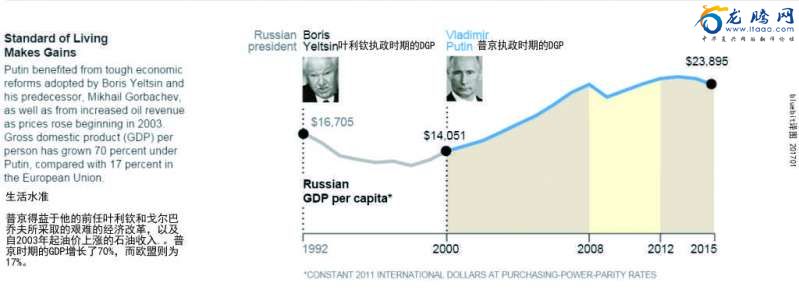

Standard of Living Makes Gains Putin benefited from tough economic reformsadopted by Boris Yeltsin and his predecessor, Mikhail Gorbachev, as well asfrom increased oil revenue as prices rose beginning in 2003. Gross domesticproduct (GDP) per person has grown 70 percent under Putin, compared with 17percent in the European Union.

生活水准普京得益于他的前任叶利钦和戈尔巴乔夫所采取的艰难的经济改革,以及自2003年起油价上涨的石油收入.。普京时期的GDP增长了70%,而欧盟则为17%。

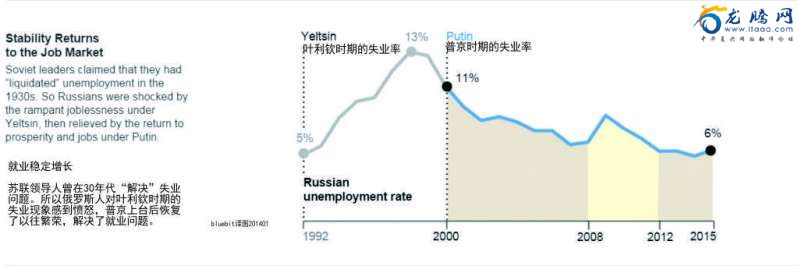

Stability Returns to the Job Market Soviet leaders claimed that they had “liquidated”unemployment in the 1930s. So Russians were shocked by the rampant joblessnessunder Yeltsin, then relieved by the return to prosperity and jobs under Putin.

就业稳定增长苏联领导人曾在30年代“解决”失业问题。所以俄罗斯人对叶利钦时期的失业现象感到愤怒,普京上台后恢复了以往繁荣,解决了就业问题。

CorruptionPersists and Wealth Rises Despitewidespread support for Putin, many Russians view their government as highlycorrupt, seeing the sudden dramatic rise in the number of billionaires asevidence. More billionaires live in Moscow than in any other city in the worldbesides New York and Hong Kong.

腐败依然,财富增长 尽管普京受到广泛支持,但有很多俄罗斯人认为他的政府相当腐败,如亿万富翁的快速增加便是例证。放眼世界,除纽约和香港,住在莫斯科的亿万富翁,比其他任何城市的都多的多。

An ActiveEveryman Putin has publicly participated in a widevariety of traditionally masculine endeavors, in contrast to the aging andinfirm Yeltsin, whom he succeeded on December 31, 1999.

活跃的普通人 普京公开参加各式各样“男人雄性”的传统运动,而年迈的叶利钦在1999年12月31日就取得了成功。

MATTHEW W. CHWASTYK AND JOHN TOMANIO, NGMSTAFF; FARHANA HOSSAIN. SOURCES: ANDERS ÅSLUND, ATLANTIC COUNCIL; WORLD BANK;TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL; FORBES.COM; LEVADA CENTER; GALLUP.COM. PHOTOS (LEFTTO RIGHT): ALEXANDER NATRUSKIN, REUTERS; RUSSIAN PRESIDENTIAL PRESS ANDINFORMATION OFFICE; ALEXEY DRUZHININ, AFP/GETTY IMAGES; DMITRY ASTAKHOV, GETTYIMAGES; AFP/GETTY IMAGES; ALEXEY DRUZHININ, RUSSIAN PRESIDENTIAL PRESS ANDINFORMATION OFFICE; DMITRY ASTAKHOV, GETTY IMAGES (以上图片来源:盖蒂图片社 bluebit注)

It is a common refrain in Nizhniy Tagil:young people with young-people dreams, locked out of them by the reality ofPutin’s Russia. They want to travel, but their salaries are in rubles, thue of which has been halved by the economic crisis. Some want to open theirown businesses but don’t know how to scale the dangerous slopes of localcorruption. So they train their sights lower. They want a house or apartment, acar, and a family. The things they crave are also the things that many of themdidn’t have precisely because their families survived the Nineties.

下塔吉尔有个普遍情况:年轻人有年轻人的梦想,但普京下俄罗斯的现实束缚住了这些人的梦想。他们想旅行,但在经济危机下他们的卢布贬值近一半。他们想开公司,但不知道如何避开腐败。因此黯然神伤。他们梦想有个房子、车子和美满的家庭。他们所渴望的也是别人也没有的东西,因为他们同是90年走过来的。

“The Nineties were very hard for us financially,” Alexander Kuznetsov,a 20-year-old from Nizhniy Tagil, tells me. “In 1998 my dad left the family.”Alexander was three. “My mom’s entire salary went to feed me. I didn’t havemany toys,” he says. “I’m alone in the family.” That left its mark. “For me themost important thing is family,” Alexander tells me as we sip coffee in a caféoff the main square. “I don’t want to strive for high professional posts andhave an empty home.”

一位20岁来自下塔吉尔的Alexander Kuznetsov 跟我说道,“90年代,我们的经济非常困难,1998年我爸离开了家,我三岁,我妈赚的钱全给了我,那时没多少玩具可玩,我基本一个人独自待在家”,这给我留下的印象非常深刻。“对我来说家人最为重要”。“升职我就不想了,只希望全家能聚在一起”当我们在广场的咖啡馆喝咖啡时Alexander对我说道。

His father fought in the firstChechen war, in 1994. “Don’t join the army, son,” he advised Alexander. That was the sum total of his father’s recollections of theNineties. But Alexander isn’t bothering to find a way out of the universaldraft. “I always wanted to join,” he explains. “Everyone in my family was inthe military. My great-grandfather fought in World War II.” Plus, militaryservice opens up some of the more lucrative job prospects for a young man inRussia: work in the police or the Federal Security Service, or FSB, thesuccessor to the KGB. The army would give him a shot at being a cop like hisfather. “I really want to have a stable income,” Alexander says.

他父亲在1994参加过车臣战争,父亲曾劝他“儿子,别去参军”。这就是他对爸爸关于90年代的全部记忆。而Alexander却别无出路。“我总是想去当兵”,他这么解释道。“我家人全当过兵,爷爷还参加过二战打过仗”。此外,军队对于俄罗斯的年轻人开出了令人无法拒绝的,当兵退役后的优越条件:比如去当警察、当联邦安全部员工,没准还能去KGB(克格勃)。军队能给他能像父亲那样的警察工作。“我真的想有一个稳定的收入” Alexander说道。

An energetic 27-year-old entrepreneur, RadikMinnakhmetov straightens Putin’s official portrait, prominentlydisplayed in his office next to one of the president of Tatarstan, a Russianrepublic about 450 miles east of Moscow. At 24, Minnakhmetovbecame the head of a new futuristic stadium in Kazan, Tatarstan’s capital.

一位27岁大,精力旺盛的,名为Radik Minnakhmetov的企业家,正摆正普京的官方画像,一同把鞑靼斯坦共和国总统画像,突出放在他办公室明显的位置。鞑靼斯坦共和国位于俄罗斯东450公里,Minnakhmetov在24岁时就当了该国新体育馆的领导

Students in Nizhniy Tagil celebrate “LastBell,” the end of classes. Wearing sashes that say “Graduate,” they cavort onLisya Mountain, an extinct volcano. The day, at the end of May, is a big eventfor students across Russia.

在下塔吉尔当学生上完最后一堂课后,听到“下课铃”到跑出来庆祝,身披勋带高喊“毕业啦”他们在lisya山上欢呼雀跃。对于俄罗斯各地的学生来说五月的最后一天是他们重要的一天。

As Alexanderand I talk, his friend Stepan, a strapping, smiling young man with a blond buzzcut, bounces in to join us. “So,” he says, flashing me a mischievous grin,“you’re writing about what it was like in the Soviet Union? People lived a lotbetter then.”

当时Alexander跟我说,和我们一起有个叫stepan的朋友,体格强壮,发色金黄、爱嬉笑的年轻人。他调皮地说道“听说你喜欢在写苏联时候的东西?那时候的生活人们比现在过的好多了。”

“What!” exclaims Alexander. “Lived better?!No, we didn’t!”

“什么!过得好?我们可没有!” Alexander说道,

They argue about what it was like to livein Soviet times, until Stepan, who was born in 1992, realizes he has a questionfor me: “You Americans are pressuring us, slapping us with sanctions,” he says.“What are you preparing for us? A war?” He explains why it was right for Russiato annex Crimea and for Putin to stand up to the West.

正当他们争论生活在苏联时期究竟有哪些好时,92年出生的stepan给我抛出个问题“你们美国人在逼我们,制裁我们,你们都对我们做了啥,一场战争?”,他给我解释了俄罗斯为什么要拿下克里米亚,为何普京反抗西方是正确的。

Stepan is reluctant to tell me his lastname because I’m an American journalist, but when it’s time for me to go, heoffers me a ride. “Really, though,” he says to no one in particular as we wheelthrough the city, “I want to get out of here.”

因为我是名美国记者,Steapn不太愿意告诉我他的姓,我快到走的时候,他说,“不过、这座城市确实没有啥可留恋的,我想出去看看。”

Out of where? I ask. Nizhniy Tagil?

去哪?下塔吉尔?我问道。

“No,” he says. “Russia.”

“不,是俄罗斯”他说道。

After his patriotic bluster, this wasunexpected. Why? I ask him.

他激动地辩词让人吃惊。于是我接着问他“为什么?”

“There’s nothing to do here,” he says without any bitterness. “Noopportunities, no way to grow and develop and make something of yourself.”

“我以后的打算?”他琢磨一会,微笑到“去俄罗斯联邦安全局呗。”

What’s your backup plan? I ask.

你的B计划是啥?我问

“What’s my backup plan?” he repeats, smiling broadly. “Join the FSB.”

“我的B计划是啥?”他笑眯眯的重复道。“加入FSB(联邦安全局)。”

At a drug rehabilitation center outsideNizhniy Tagil, three young men soap up after sweating in a sauna. Russia’syoung appear to enjoy this traditional pastime as much as their elders do.Almost 6 percent of the population uses drugs regularly or is addicted, a 2013government study found.

在下塔吉尔郊外的一个戒毒中心,三个年轻人在蒸桑拿出汗后打着肥皂。俄罗斯的年轻人似乎和他们的长辈一样,非常享受这种传统活动。2013年政府研究发现,几乎有6%的人吸毒上瘾.。

“Those who were born in the U.S.S.R. and those born after itscollapse do not share a common experience,” wrote Svetlana Alexievich,who won the Nobel Prize in literature in 2015. “It’s like they’re fromdifferent planets.”

“那些出生在苏联崩溃前和崩溃后时期的人基本没什么共同语言”。曾得过2015年诺贝尔奖的Svetlana Alexievich写到。“他们好像来自不同的星球”。

The Soviet Union drowned in a surge ofoptimism. Many believed Russia would quickly become a flourishing,Western-style democracy. But the optimism of 1991 dissipated in a decade ofoften depressing contradictions. With the end of the planned economy cameuntold riches or entry into a new middle class for some; for others it was asudden plunge into poverty. Previously unavailable goods flooded store shelves,while the money to buy them periodically lost its value. Crime, especially incommerce, skyrocketed. Politics came out into the open, but many Russians cameto see it as a dirty business.

苏联被一波乐观主义大潮冲垮。有相当多的人相信俄罗斯马上就能过上繁荣富庶的西式生活、变成民主国家。但91年的这种乐观情绪经过10年的消磨逐渐散去。随着计划经济的终结,有些人发了大财,有的人步入中产阶级;但另一些人却忽然陷入了贫穷。以前无法买到的商品,现在商场货架上摆的到处都是,而钱却变的不值钱了。犯罪,尤其是经济犯罪,急剧增长。政治虽可以公开参与,但许多俄罗斯人把它看作是一个肮脏买卖。

Russians struggled to adjust to thisforeign reality. It was a time of unprecedented freedom, but many found itdeeply disorienting. “When these [Western] values encountered reality andpeople saw that changes came too slowly, these values receded into thebackground,” says Natalia Zorkaya, a sociologist withthe Levada Center, an independent polling organization in Moscow. Instead, shesays, the younger generations are adopting “the pillars of Soviet society.”

俄罗斯人努力地去适应这种外来的现实。这是一个前所未有的自由时期,但有很多人却因此无法自拔。“当西方价值观遇到了现实,人们感觉变化太慢,因而这些价值观逐渐消散”,莫斯科莱瓦达民调中心,社会学家,Natalia Zorkaya说道。相反的是,他接着说道,这代年轻人相信“社会主义信仰”。

Sasha, Alexander, Stepan, and their cohort do live on a planet different from the one theirparents and grandparents live on, yet they are in some ways becoming even moreSoviet. It’s a strange thing: These young men and women know little of theprivations, habits, and cruelty of Soviet life. The Putin generation doesn’tcarry this wound. Their desire for staid normalcy—intact families, reliable, ifunsatisfying, jobs—is their response to what they lacked in the Nineties andfound in the Putin era.

Sasha、Alexander、 Stepan还有他们这代人,同他们的父辈人确实是在这个星球上的不同时期生活过,然而,他们在某些方面却变得更加“苏联”。可令人奇怪的是,这些年轻人只是知道一点苏联的残酷、行事风格。普京时期没了这种伤痛。 他们渴望有着稳固的正常家庭,工作要是不满意——他们会发现在普京时期,怎么也比90年代的强。

Students take a break at Muhammadiyamadrassa in Kazan, a city on the Volga River that is about half ethnic Russianand half Tatar. Most Tatars are Muslim; Islam, Russia’s second largestreligion, is followed by about 7 percent of the population. The school teachesreligion, humanities, linguistics, and Tatar history and culture.

一群在Muhammadiya喀山,伊斯兰学校休息的学生,喀山,一个坐落在伏尔加河畔的城市,城市人口由俄罗斯、鞑靼人组成,人口各占一半。大多数鞑靼人都是穆斯林;伊斯兰教,俄罗斯的第二大宗教,约占7%俄罗斯人口这家宗教学校,教,人文科学,语言学,和鞑靼历史和文化。

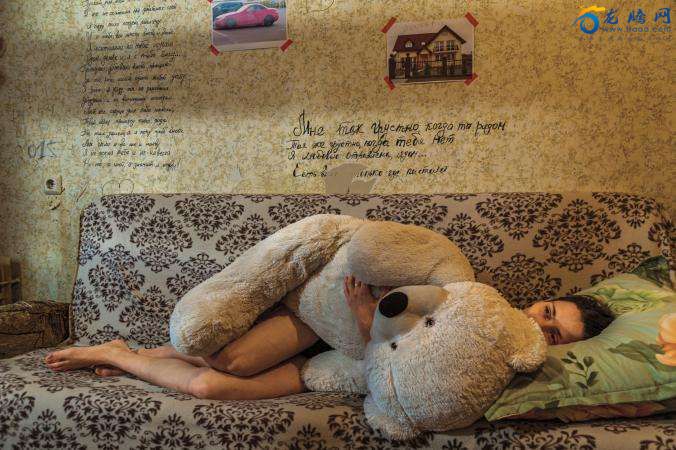

Left: With some seven million Instagramfollowers, 29-year-old TV actress Nastasya Samburskaya (@samburskaya) is one ofRussia’s biggest social media stars. Nevertheless, like many Muscovites, shelives in a small apartment. No different from youth in many countries, youngRussians rarely part with their smartphones. Right: A 24-year-old sex workerwrites lyrically, on the wallpaper of her St. Petersburg apartment, of love,heartbreak, loneliness, and thoughts of suicide. Her paid trysts are arrangedon the Internet.

上图: 29岁的电视演员Nastasya Samburskaya(@ samburskaya)是俄罗斯网上最大的自拍网站明星,大约有七百万粉丝。然而,和不少莫斯科人一样,他也住在一个小公寓里。和其他国家的年轻人一样,她手里的智能机跟她的命根子一样、难以割舍。

下图:一位24岁的性工作者在她圣彼得堡公寓里,墙壁上的壁纸写着她写的关于她爱情、伤心、孤独还有自杀倾向的歌词。她在自己的网站安排“工作”。

Yet they are profoundly insecure.Sixty-five percent of Russians between ages 18 and 24—that is, the firstgeneration born after the Soviet breakup—plan their lives no more than a yearor two ahead, according to the Levada Center. “It’s a very egotisticalgeneration,” Zorkaya says, but adds, “It’s a very fragile generation.” They arealso politically inert: Most don’t know about news events the state doesn’twant them to know about, and 83 percent say they have not participated in anykind of political or civil society activity.

可他们仍有种深深地不安全感。俄罗斯介于18至24的年轻人口占5%-6%,这是苏联解体后第一批出生的人,他们从不会规划自己超过一两年的生活,据列瓦达中心表示。“这一代人非常自私,也是相当脆弱的一代人,”Zorkaya说到。他们对政治也不敏感,他们大多数人不知道什么叫“新闻封锁”,83%的群众表示他们从没参加过任何政治、社会活动。

Liza meets me in the glittering white lobbyof one of the many glass towers—some blue spirals, some coppery shards—thatmake up Moscow City, a financial center that looks like a cross between Londonand Shanghai. I follow her through tunnels linking the towers underground withcafés, shops, and an exhibit with paintings of Putin and Russian ForeignMinister Sergey Lavrov. We order lunch, and Liza, a stylish young woman withlong, curled blond hair, dimples, and an expensive watch, tells me her story asshe slurps her borscht. She asks me not to use her last name because shedoesn’t want to upset her parents.

在一个有由好几座由闪闪发光的玻璃塔组成、塔上涂有蓝色条纹和贴有金(铜)箔内的塔内白色大厅里,我丽莎在那里见了面。莫斯科市看起来像似一个金融中心、伦敦和上海的混合体,这座塔成了该市的地标。塔下面有个地下通道,通道里有咖啡馆、商店、以及画有普京和俄罗斯拉夫罗夫外长的画廊,我跟着丽莎从里面走过。我和莉莎点了份午餐,一位卷曲金发,面戴酒窝,带着好表、喝着罗宋汤的年轻时尚的女子,跟我讲了她的故事。她让我不要写她的姓,因为她不想让她父母生气。

She was born in Blagoveshchensk, in theRussian Far East, in 1992. A year before, her father, a history teacher, hadbeen out in the streets of Moscow, cheering the arrival of democracy. But onreturning home after the Soviet Union’s demise, he was forced to find otherways to support the family. He began crossing the border into China andcarrying back anything from clothes to appliances for resale in Russia. “Iremember him coming home with money sewn into his shirt so that he wouldn’t getrobbed,” Liza tells me.

她1992年出生,出生地是在俄罗斯远东地区的海兰泡。一年前,她当历史老师的父亲还奔走在俄罗斯街头,为民主呐喊。苏联解体后他回了家,他不得不找个养家的法子。他开始越过边境跑到中国,并从中国带回衣服电器等什么东西到俄罗斯来卖。“我记得他怕被偷,回来时把钱缝在了他的衬衫里,”

She’s a corporate lawyer at a large Westernfirm. It’s fine, but it’s not what she wanted to do. “I always wanted to be ajournalist; I was always writing,” she says, noting that her grandmother keptall her short stories. “But my parents told me journalism isn’t serious. It’s avenal profession”—a relic of the 1990s, when journalism here was bought andsold like any commodity—“You won’t make a lot of money. You’re the oldest andthe smartest; you need to go into a solid profession so you can feed yourselfand take care of your sister.” Along the way her parents separated. Herfather’s business eventually took off, and Liza was able to spend a year ofhigh school in Oregon and also study abroad in London.

她在西方一家大公司当名律师。工作是很好,但她不怎么喜欢。“我总想去当一名记者,而且一直在写作”,她还知道她奶奶还留有他写的小说。但我父母跟我说新闻不怎么严谨。这是90年代就有的见利忘义的职业。做新闻和卖东西一样,“你赚不了多钱。你是家里老大还聪明,应该找个稳定的工作,你才能养活自己照顾好你的小妹。”尽管他的父母离婚。他父亲的生意还是有了起色,丽莎能念上俄勒冈念一年高中,也能去伦敦留学。

A chic restaurant in an affluent suburb ofKazan attracts the young, fashionable set. Voda|Sneg(Water|Snow), on the shore of the Volga River, offers a range of entertainmentoptions that change with the seasons. In summer there’s outdoor dining, a dockfor boats, and swimming; in winter, skiing, snow biking, and dogsledding.

在喀山郊区,一个别致的餐厅吸引了大批年轻时尚人士。随着伏尔加河畔的季节变化,这里经常举行“冰、水”节。夏天,餐厅户外停泊着小船,还可以游泳;入冬可以玩滑雪、骑雪地自行车和狗拉雪橇。

Left: At a classy high school prom at St.Petersburg’s elegant Grand Hotel Emerald, students help themselves to a pyramidof cocktails. The end of communism brought both poverty and wealth to Russiaand created a small middle class. For the young who lived through the volatile1990s, economic security remains a top desire.Right: Seminary students atMoscow Theological Academy in Sergiyev Posad study the New Testament,liturgical music, icon painting, and other subjects. Brutally repressed by thecommunists, the Russian Orthodox Church has seen a resurgence under Putin, whosees it as an ally in his bid to restore the nation to greatness.

上图:在圣彼得堡典雅奢华的翡翠酒店里举行着高中毕业舞会,学生们在一齐搭鸡尾酒塔。共产主义的结束造成了俄罗斯的贫富分化,催生出一小批中产阶级。但对于那些经历了动荡的90代年轻人来说,经济安全仍是他们最为关注的。

下图:莫斯科谢尔盖耶夫新约神学院里的学生,可以研习,唱诗音乐,圣像画和其他科目。(苏联时期下的)俄罗斯东正教受到共产党的残酷镇压,而在普京时期它们看到了希望,它们把普京看作是让“国家再次伟大”的推动者。

A modern Westernized woman, she tells hermother about her boyfriends and the drug-fueled parties she attends. But insome ways she is very, very Russian. “Putin irritates me,” she begins, soundinglike many in the oppositional, educated milieu of Moscow. “But just leta foreigner try to criticize him! I will always defend Russia.” When she was inLondon, she says, people constantly made fun of Russia and Russian women,mocking them as mail-order brides. “It was offensive to the point of tears, tosit there and hear outsiders making fun of us,” she says.

一位时髦西方化的女子,她跟他妈妈表明他和男朋友(们)一起参加过毒品派对。但在某些方面,她非常非常地俄罗斯。“普京让我很不舒服”他说话声音像没受过良好教育的人发出来的。“还是让外人处理他吧!我一直是俄罗斯的守护者”。她说,当她在伦敦的时候,人们总是取笑俄罗斯和俄罗斯的女人,嘲笑他们是邮购新娘.。她说:“坐在那儿,听到外人取笑我们真让人反感。”。

This is as political as she gets thesedays. Back in 2011 Liza became interested in liberal politics, which was allthe rage in Moscow. She joined Amnesty International and the liberal Yablokoparty as an observer for the December parliamentary elections. Shewas assigned to the polling station at her little sister’s school and wasshocked to see teachers stuffing ballot boxes. When Liza tried to saysomething, they screamed at her and made her sit in a corner while theprincipal blocked her view. This was happening all over the country. Manyelection observers caught it on their phones and put the proof online, whichsparked a mass protest movement in Moscow and major cities unlike any Russiahad seen in 20 years.

她遇到的这些事都是因为政治原因。回首2011年,自由政治让丽莎相当感兴趣,这也让当时所有莫斯科人为之疯狂。他加入了大赦国际,并参加了自由博卢党(俄罗斯统一民主党),当了名十二月议会选举观察员。她被分配到她妹妹学校的投票站,看到老师们的投票情况,让她感到非常震惊。当丽莎想努力去说点什么的时候,他们却冲她大喊,让她去一边去,然后校长走过来挡住她的视线。这种情况全国都在上演,有许多观察员都用手机拍下来这一切,并发到了网上。与近20年来城市中的抗议活动不同的是,这引发了莫斯科和一些主要大城市的大规模抗议运动。

Liza, however, lost her nerve. “I washysterical,” she tells me. “I spent two hours crying.” After that she decided,“No more politics. Ever. This doesn’t concern me, and I’m not strong enough tofight.” It’s a promise that she hasn’t broken, even as the ruble has crashed,cutting into her ability to do the other thing she loves most: travel. “Yes,it’s terrible; there are fewer opportunities,” she says, but she refuses toseek an answer in politics. “It’s a psychological block.”

无论怎样,这让丽莎很丧气。他跟我说“我都已经疯了,还哭了两小时。”后来他下决心“再也不碰政治了,跟我又没啥关系,没必要那么使劲往前冲”。这是一个无可奈何的决定,即使卢布崩溃,外出旅游的梦想被破灭。“是的、这很可怕,(改变的)机会越来与渺茫”,但他不想再在政治上寻找答案,“我已死心了”

Kseniya Obidina, Liza’s law school friend,sees things similarly. Also the child of divorce, she says family and stabilityare of primary importance to her. She wants a secure, well-paying job. Shewants to be able to afford travel and to support her mother and sister. Thisdream has become more remote, though, with the political and economic crisis:Kseniya wants to work at foreign law firms, but they are increasingly packingup and leaving the country. Like Liza, she refuses to think about politics. “Idon’t see the point of talking about something you can’t influence. Talk fortalk’s sake isn’t interesting,” she says as we sit in a Moscow Starbucks. As weleave, she adds, “It’s better to know and be quiet. It’s better not to speakup. Why spoil your mood?”

Kseniya Obidina,莉莎法律学校的朋友,跟他的想法差不多。她也是单亲家庭的孩子,对她来说一个稳定家庭最重要的。她想要一份安全,报酬优厚的工作。她希望能够负担得起旅行费用,养起她的母亲和妹妹。但随着政治经济危机的到来,这个梦想开始变得越来越遥远,Kseniya想在外国律师事务所工作,而且有越来越多的人打算收拾下东西就离开这个国家。像丽莎一样,她对政治很反感。我们坐在莫斯科星巴克时她说道,“我不明白讨论你无法影响的事情到底有何意义,谈这个话题一点也没有意思,”。当我们要告别时,她补充道:“有些东西最好是看懂了但别嚷嚷。保持安静更好。自己为啥要找不自在呢?“

Tech companies like NeoPhotonics, a U.S.firm with operations in Moscow, employ young workers at good wages, helping toexpand the middle class. In Soviet times scientists were secluded in isolatedcities like Akademgorodok.

像在莫斯科NeoPhotonics美国高科技公司,高薪聘请年轻工人,帮助增加中产阶级。苏联时代,科学家们只能呆在像Akademgorodok这样与世隔绝的偏远城市。

How did they come to be this way? VladimirPutin is a big part of the answer. He came to power in 2000 as an anti-Ninetiescandidate just as this generation was becoming aware of the world around them.He promised to bring prosperity and security. Coasting on historically high oilprices and economic reforms implemented in the Nineties, Putin was able tofulfill much of that promise but at the expense of democratic freedoms.

他们是怎样走上这条路的?主因就是普京。当这代人盼望能和周围世界一摸一样时,作为一个可以结束90年代灾难的候选人,普京于2000年登上权力宝座。他许诺能带来繁荣安全。许诺在油价下滑阶段,对90年代来的经济状况进行改革,普京或许能完成他所所承诺的大部分,但却是以牺牲民主自由做为代价。

Stability and economic well-being becamethe ideology of the day, peppered with a heavy dose of nostalgia for theU.S.S.R. and a whitewashing of its sins. Putin called the disintegration of theSoviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century.Whoever didn’t feel that, he said, “doesn’t have a heart.” Joseph Stalinbecame, in the business-friendly lingo of the day, an “effective manager” whowent a bit too far. Textbooks and television came to reflect this new, state-sanctionednostalgia. Today 58 percent of Russians would still like to see a return of theSoviet order, and some 40 percent see Stalin favorably.

稳定和经济健康发展,不断地粉饰苏联,洗刷苏联的罪恶成了当今理念。普京称苏联解体是“二十世纪最大的地缘政治灾难”。还说“无论谁都接受不了这种情感”。(俗话说)在生意环境不错的情况下,谁管理得好,谁就能走的更远。斯大林就是那位管理人。书本和电视节目折射出了这种怀旧情怀,还得到了官方首肯。现在有58%俄罗斯人依然盼望回归苏联,约有40%的人对斯大林表示认可。

THEPUTIN GENERATION WANTS INTACT FAMILIES AND RELIABLE, IF UNSATISFYING, JOBS. ITASSOCIATES THE SOVIET UNION WITH LONGED-FOR STABILITY.

普京这代人希望家庭完整、稳定,但如果没有一个让人满意的工作。它或许步入苏联后尘。

Much of post-Soviet life has been a haplesssearch for a uniting idea. At first it was democracy; then consumerism became astand-in for Westernization. “Modernization came through consumption, butthat’s not enough,” says sociologist Zorkaya. Ikea,which came to Russia in 2000, became wildly popular among the new middle classas a way to affordably live in a stylish European—that is, non-Soviet—way. “Itbecame a symbol of how you could civilize your life without a lot of money,”she says, “but the fact that behind this decor is a totally different conceptof human beings and values, somehow it doesn’t connect for Russians.”

苏联这一生大部时间都在寻求一个统一的思想。起初它很民主,后来西式享乐思想占了上风,“西式生活需要花钱,但这还不够”,社会学家Zorkaya Ikea说道。宜家公司于2000年来到俄罗斯,它时髦又经济的,豪无苏联影子的欧式生活品味,深受新晋中产阶级的欢迎。有了它就是成为文明人的一种象征,且价钱便宜实惠,”她说,“但事实上,这公司的背后有着与人们思想完全不同的价值观,在某种程度上它与俄罗斯人没有什么关联。”

Since the beginning of his thirdpresidential term, in 2012, Putin has promoted an even more aggressiveneo-Soviet ideology, both at home and abroad. He fought to keep former Sovietrepublics, like Ukraine and Kazakhstan, in Moscow’s sphere of influence andflexed Russia’s military power in distant Syria. A series of laws promotedtraditional social values and made dissent even more dangerous. One result is ageneration whose dreams are the embodiment of everything Putin desires them to be:conformist, materialist, and highly risk averse.

自2012年普京第三届总统任期开始,他推动了一个更加激进的新苏联意识形态,无论是在国内还是在国外。他努力让前苏联(加盟)共和国,如乌克兰、哈萨克斯坦,维持在莫斯科的势力内,还在遥远的叙利亚展示俄罗斯的军事力量。一系列的法律巩固了传统社会价值观,并使得持有异议变的更加危险。一代人有一代人的梦想,普京这代人的梦想是:安分守己,唯物主义,和防患未然。

Much is made of Putin’s stratosphericpopularity—at the time I reported this article, Putin had the approval of 80percent of Russians polled. But Russians between the ages of 18 and 24 approve ofhim at a higher rate than any other age group: 88 percent. More than any othergeneration, they are proud of their country and its stature in the world,associate its military prowess with greatness, and believe in its future.

此时,当我发在表这篇报道时候,普京的民调得到了80%俄罗斯选民的支持,普京有着相当高的人气。而且选民中占88%的18岁到24岁的俄罗斯年轻人比其他年龄段的人更为认同普京。他们比其他任何一代人对自己的国家和世界地位感到更自豪,再联系到它自身庞大的军事力量,他们更相信俄罗斯的未来。

Before the “Day of theVillage” celebrations in Nikolskoye, 175 miles northeast of Moscow, youngpeople do what young people do everywhere entertainment is sparse: hang out andflirt. Until the recent downturn, the country’s oil-fueled economy expandedrapidly, and Russia’s young flocked to its cities to seek higher paying jobs.

莫斯科东北部175英里,利斯科耶的“乡村日“节日活动。无所事事的年轻人做着以前很少去做的事儿——闲逛和打情骂俏,直到最近的低迷时期,俄罗斯的石油经济迅速发展,俄罗斯的年轻人涌向城市寻找高薪工作。

In a dark, narrow courtyard in Novosibirsk,between two 19th-century brick buildings, I find the local bohemians drinkingbeer and listening to electronic music. It’s here that Filipp Krikunov,born in 1995, opened an art gallery. Ducking away from the gathering, he showsme around. One room is lit with a fluorescent pink light, the wall arrayed withshelves holding mini-busts of Lenin, painted in silly patterns. In the nextroom young artists have cobbled together mind-bending waysto take selfies: Stick your head into this cardboard box full of shatteredmirrors. Stick your head in another to find the remains of a Burger King meal.

入夜后,在Novosibirsk两个19世纪砖瓦建筑中间的小广场里,我发现有不少本地人在那儿喝啤酒和听电子音乐的。1995年出生的Filipp Krikunov在这里开了家画廊。他推开应酬带着我一起出来走走。一家房间里闪着粉红色的荧光灯,墙上的支架摆着微型列宁半身像,半身像上的颜色涂的有些傻里傻气。在另一个房间里,一位年轻的艺术家“扣”出来两个可以折射内心世界的东西,例如把头伸进其中一个里面满是碎镜片的盒子里。要是把头伸进另一个盒子里,你会发现里面装着一块剩汉堡。

One of Filipp’s friends and partners in thegallery bounds up and shakes my hand. “We just found out that they didn’t buryanyone under this space,” he gushes. After Filipprented the rooms, he and his friends realized that the building next doorhouses the FSB. In the 1930s it was called the NKVD, and it killed as many as1.2 million people. Often the NKVD’s victims were shot and buried on-site. ButFilipp’s gallery, Space of Modern Art, lucked out. No bones in thebasement here. Just hipsters in the mild Siberian summer night.

一位画廊合作伙伴,Filipp的朋友,握着我的手几乎喊着说。“我们才发现,在这个空间下他们毁掉不了任何人”。之前Filipp租完房子之后,他和他朋友才发现隔壁就是FSB(克格勃)。FSB在上世纪30年代又被叫做NKVD(内务人民委员部),该部造成了120万人死亡。NKVD的受害人通常被枪毙后就地掩埋。但在filipp的画廊,这座现代艺术空间里,还算侥幸。这房间里地下室没留有骨头。只有温暖的西伯利亚夏夜里的嬉皮士。

I had met Filipp earlier that day at a chicNovosibirsk café, surrounded by impossibly fashionable young women with veryobvious lip jobs. Novosibirsk is Russia’s third largest city, a center ofindustry and scientific innovation. There’s a lot of money here. Filipp,though, didn’t see much of it. He grew up without a father. Like many youngRussians, he was raised by his mother and grandmother. His great-grandfatherfought in World War II and was later purged by Stalin. His grandmother became arenowned chemist, and his mother also worked in science. But the women’spassion was politics. “All the main hashtags at home are politics,” Filippsays.

早些时候,我和filipp曾在一个名为Novosibirsk挺有格调的咖啡馆碰过面,当时周围坐着的全是浓妆艳抹的年轻时尚女士。Novosibirsk是俄罗斯第三大城市,工业和科技创新中心。这里“钱途”满满。尽管filipp到现在还没摸到过它。和其他俄罗斯人一样,他从小没了父亲,是妈妈和姥姥给他拉扯大的。他的曾祖父曾参加过第二次世界大战,后来被斯大林清洗掉了。他的祖母后来成了一名着名化学家,他的母亲也从事科学工作。但女人们的激情都是因为政治。“所有国内主要的恶毒攻击都源于政治,”Filipp说到。

Mikhail Vasilev, a 29-year-oldbilliard-equipment salesman, practices his skateboard moves in Moscow’s TriumfalnayaSquare near a statue of Vladimir Mayakovsky, a poet whoextolled the 1917 revolution. Russia’s young people have more freedoms thantheir parents and grandparents could ever have imagined.

Mikhail Vasilev,一位29岁的台球设备销售上,他在莫斯科Triumfalnaya广场的Vladimir Mayakovsky塑像附近玩他的滑板车,Vladimir Mayakovsky是位诗人曾参加1917年革命。俄罗斯的年轻人比起他们的爸爸妈妈奶奶们有着更大的自由。

Filipp was 16 when the pro-democracyprotests broke out in Moscow and spread to cities like Novosibirsk. Tens ofthousands poured into the streets to demand free and fair elections, yet theprotests felt more like block parties than demonstrations. Filipp too was fedup with Putin. “Messages were being sent to him, messages of discontent, andyet there was no dialogue with those people,” Filipp says. He didn’t recognizethe Russia that Kremlin-controlled television showed. “That was a differentcountry,” he says. “I didn’t know a single person like that.”

Filipp 16岁时,支持民主的抗议活动从莫斯科爆发并蔓延到像Novosibirsk这样的城市。成千上万的人涌上街头要求举行自由公正的选举,然而抗议活动更像是游行而不是示威。Filipp烦透普京了。他说“表达不满的消息是传到普京那里了,但却没人与这些人进行对话”。他不承认克里姆林宫所掌控着的电视媒体下的俄罗斯。“这不是同一个国家,”他说。“我不认识电视里的那个人。”

“I went to the protests. I tried to be politically active,” Filipptells me. “It was boiling inside me. I wasn’t thinking about anything else. Thewhole country is rising in protest, and I’m part of it.” But he was soondisappointed. “I looked around, and the people at the rallies weren’t mypeople. I wasn’t totally comfortable,” he says. “And it didn’t lead to anything.”

“我加入了抗议活动。我积极地参与政治活动,”Filipp告诉我。“它让我激情澎湃。心里只想着它。整个国家都在抗议,而我是其中一份子”,但他很快就失望了。“我环顾四周,参加集会的人我几乎都没见过。这让我很不大舒服,“他说。“最后毫无结果。”

That’s not quite true. The protests didchange things, just not for the better. In May 2012 the Kremlin cracked down.Since then dozens of people who attended protests have been rounded up, tried,and jailed. The political situation in the country only worsened asPutin—feeling betrayed by the middle class he felt he had created with hispolicies—pursued an increasingly authoritarian line. He publicly labeledliberals who advocated for freedom and democracy “national traitors” and “afifth column.”

也不是完全没起作用。抗议确实改变了一些东西,但结果不怎么好。那就是克里姆林宫在2012年5月进行镇压。从那时起,数十个参加抗议活动的人被捕、审判、坐牢的坐牢。这个国家的政治形势只会恶化,因为普京觉得那些中产阶级背叛了他所制定的“缓慢独裁”政策。他公开地对鼓吹自由民主的自由主义者打上“民族叛徒”和“第五纵队”的标签。

The harsh response left a deep impressionon the Putin generation: It taught them to stay out of politics. “I decidedthat either I fight this system,” Filipp says, “or I live in a differentsystem”—the world of art. “There’s more good in it,” he says. “Politics arenerve-racking. You’re constantly unhappy; you’re not enjoying your life.”

这种粗暴做法给普京这代人留下了深刻的印象,既,教会他们要远离政治。“我决定我以后再也不关心这个体制了,”Filipp说到,“或许我可以生活在一个与之完全平行的“艺术世界”里。“里面要多好就有多好”他说到。“政治会使人心烦意乱。你无法快乐;无法去享受你的生活。”

Putin is up for reelection in 2018. Thereis little doubt that he will run again and even less that he will win anothersix-year term. That would mean he would be in power until 2024,if not longer. By then Filipp,who was five when Putin first became president, would be 29. Is he comfortableliving with Putin until then? He shrugs. “I’ve lived my whole life with myright hand, and it’s fine.”

普京将在2018年再次进行竞选。毫无疑问,他会扶摇直上,赢得下一个六年任期。如果这样那将意味着他将会一直掌权至2024年. 普京第一次当选总统的时候,Filipp只有五岁。如2018年普京再次当选,他就已经29岁了。他会在普京掌权期间有个安逸生活么?他耸了耸肩。“我的右手都已伴我生活一生了,还不错。”

In Akademgorodok, a small academic townbuilt around Novosibirsk State University and its many labs, I meet AlexandraMikhaylova. She’s 20, with cutoff denim shorts and the dyed red hair of a punkrocker. Alexandra came from a family of scientists—her mom is a geologist andher father a physicist—who gravitated to this little town, which was founded in1957 as an incubator for science and the engine of the Soviet Union’stechnological race with the West. Since the Soviet collapse, underfundedRussian scientists have fallen behind their Western colleagues. Both ofAlexandra’s parents have gone into business.

Akademgorodok,俄罗斯一座具有学术气息的小城,这里坐落着新西伯利亚国立大学还有一些实验室,我在这里遇见Alexandra Mikhaylova。她20岁,穿着牛仔短裤,梳着一头红色朋克发型。Alexandra出身于一个科学家的的家庭,她妈妈是地质学家,爸爸是一名物理学家,他们被这个小镇吸引而来到这里。这座小镇兴建于1957年,当时是作为苏联与西方进行科技竞赛的科研之地。苏联解体以后,缺少科研费用的俄罗斯科学家已落后于西方同行。其中Alexandra父母因而下海经商了。

Now, as a third-year journalism student,she is working on a documentary about the town and its lively intellectualhistory, specifically the underground of the 1960s. “They had their own systemof government until 1966,” Alexandra tells me as we stand in the gleaminghallway of the university’s new building. Her eyes light up as she tells meabout her research into this little corner of freedom and intellectual fermentin a sea of totalitarianism. In 1966 some of these free-spirited youngscientists wrote a letter to Moscow, complaining about things they didn’t like.The response, Alexandra says, was swift. Many were fired, and strict politicalcontrol was put in place. But Alexandra’s documentary picks up again in the1980s, with the Soviet punk rock underground that spread all over the country.

现在,Alexandra作为一位有着三年学业的新闻系学生,她正在写一部关于这座城市以及这座城市的历史纪录片,尤其是该城60年代时的秘密。当我们走在国立大学新建褶褶发光的走廊中,Alexandra对我说道,“1966年以前这座城市的政治制度自成体系”,他对这里自由的星星之火和萌芽中的极权主义进行了深入研究,她跟我说这些话时,眼里闪着精光。1966年,一些具有自由精神的年轻科学家给莫斯科写了一封信,信中满是抱怨他们不喜欢的东西。Alexandra说道,事情很快有了结果。一些人被解雇,并进行了较为严格的政治控制。但Alexandra笔下的事实在80年代再次显现,地下朋克摇滚遍布苏联各地。

These days, Alexandra says, “it’s stagnant.Something’s missing. People aren’t politically engaged. When it comes to thegovernment, young people are either neutral or positively disposed. No onestands up for their opinion, and there’s a thin line between indifference andagreement.”

这几天,亚历山德拉说,“现在一潭死水,好像缺少了什么东西。人们无法参与政治。一旦涉及到政府,年轻人要么中立要么表明立场。但没人敢坚持他们的主张,冷漠和协议之间存在一条看不到的界限。”

The government is again in the censorshipbusiness. A classic rocker from the 1990s had his concert canceled here becausehe spoke out against the invasion of Ukraine. “Year after year they closeanother media outlet, the ones that show things more objectively,” Alexandrasays. More than anything, though, she is saddened that the Akademgorodokshe lives in lacks the creative fervor of the Sixties and Eighties. The societyaround her, unlike the one her parents experienced, is cautious and stale. Shelongs for a change, a shake-up. But she knows it won’t be her generation thatbrings it.

政府对公司业务反复进行审查。一个自90年代就很出名的摇滚歌手因此被取消演出,因为他曾出言反对入侵乌克兰。Alexandra说道“他们就这样一年又一年地关闭了媒体这个(发声)渠道,封杀那些展示客观情况的人。”更重要的是,这让她感到极度悲哀,他所生活在的Akademgorodok城缺少有60年代和80年代的创造激情。不像她父母所经历的那样她周围的社会是谨慎和陈腐的。她渴能有个变化,一次震动。但她清楚这绝不可能是他们这代人所能带来的。

“It’ll be the kids who are 13, 15 now,” Alexandrasays wistfully. When they are the age she is now, her generation will haveother priorities. “We’ll try to help, but if you’re 30, you’re not going tolead a revolution with a baby in your arms.”

“13、15岁现在仍是个孩子”, Alexandra伤感地说道。当这些孩子长到现在像她这么大,她们这代人可能会有其他重要的事情要去做了。“我们会全心全力地去帮助你,但是即使你到了30岁,您也无法照料还躺在你怀中革命婴儿”。

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10