【VOX】解释安慰剂效应的奇怪力量 [美国媒体]

在过去数年中,医生们注意到了一个令人困惑的趋势:越来越少的止痛药通过双盲安慰剂对照试验,该试验是测试药品有效性的黄金标准。当研究人员开始仔细研究止痛药临床测试时,他们发现1996年有27%的患者反映新药是有明显疗效的,而13年这个数字是9%.....

The weird power of the placebo effect, explained

解释安慰剂效应的不可思议的效果

Yes, the placebo effect is all in your mind. And it’s real.

没有错,安慰剂效应完全依赖你的脑洞,而且确有疗效。

Over the last several years, doctors noticed a mystifying trend: Fewer and fewer new pain drugs were getting through double-blind placebo control trials, the gold standard for testing a drug’s effectiveness.

在过去数年中,医生们注意到了一个令人困惑的趋势:越来越少的止痛药通过双盲安慰剂对照试验,该试验是测试药品有效性的黄金标准。

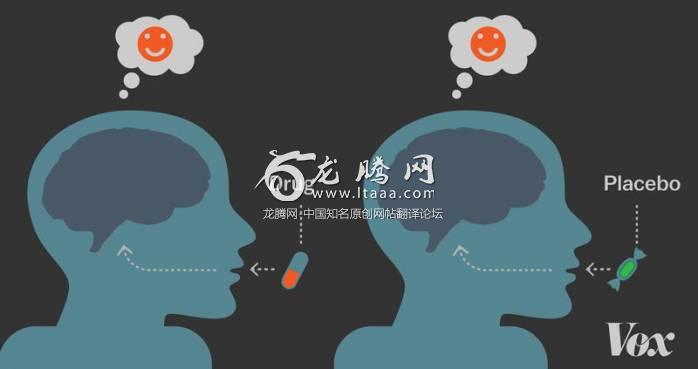

In these trials, neither doctors nor patients know who is on the active drug and who is taking an inert pill. At the end of the trial, the two groups are compared. If those who actually took the drug report significantly greater improvement than those on placebo, then it’s worth prescribing.

在这些实验中,医生和患者都不知道哪一组人员服用了试验药品或者哪一组服用了安慰剂(没用的假药)。两组人员会在实验结束时对比治疗效果。 如果服用试验药品的小组在治疗效果上明显优于安慰剂小组,那么该药品就值得上市了。

Researchers found when they started looking closely at pain drug trials in that an average of 27 percent of patients in clinical trials in 1996 reported pain reduction from the new drug compared to placebo. In 2013, it was 9 percent.

当研究人员开始仔细研究止痛药临床测试时,他们发现1996年有27%的患者反映新药是有明显疗效的,而13年这个数字是9%。

What this showed was not that the drugs were getting worse, but that “the placebo response is growing bigger over time,” but only in the US, explains Jeffrey Mogil, the McGill University pain researcher who co-discovered the trend. And it’s not just growing stronger in pain medicine. Placebos are growing in strength in antidepressants and anti-psychotic studies as well.

麦克吉尔大学的研究员们共同研究了趋势并得出结论,杰弗瑞·摩泽尔研究员解释说:‘并不是止痛药的药效不如从前,而是患者对安慰剂的止痛反应比以前更强了’。而且不仅仅安慰剂在止痛药领域愈发有效,在抗抑郁和抗精神病领域也是如此。

“The placebo effect is the most interesting phenomenon in all of science,” Mogil says. “It’s at the precise interface of biology and psychology,” and is subject to everything from the drug ads we see to our interactions with health care providers to the length of a clinical trial.

杰弗瑞说:‘安慰剂效果是最有趣的科学现象,它处于生物学和心理学的精确交界处‘。 而且安慰剂效果结果受制于我们接受的一切药品广告的影响和我们与医疗保健人员的互动程度还有医疗临床测试的时间长短。

Scientists have been studying this incredibly complex interface in great detail over the past 15 years, and they’re finding that sugar pills are stranger and more useful than we’ve previously imagined. The new science of placebo is bringing new understanding to why alternative treatments — like acupuncture and reiki — help some people. And it could also potentially allow us to one day prescribe smaller doses of pain drugs to help address the opioid crisis currently ravaging America.

在过去十五年中,科学家详尽地研究这一难以置信的复杂的多学科交界。他们发现糖丸(安慰剂)在治疗方面比我们预想中的更有效。该发现带来了对安慰剂新理解,它解释了为什么像针灸和灵气一类的替代疗法能确实地治疗大众。而且它很可能帮我们在未来的某一天解决现如今肆虐美国的鸦片类药品(吗啡成瘾之类的)危机。

Most instructively, the science finds that since we can’t separate a medicine from the placebo effect, shouldn’t we use it to our advantage?

该发现最有意义的是,正因为我们不能将安慰剂效果和药品疗效完全分离,难道我们不应该利用它使我们获利吗?

There is no one placebo response. It’s a family of overlapping psychological phenomena.

并不是安慰剂真的起作用,这是一类重叠的心理现象。

Belief is the oldest medicine known to man.

信仰是人类最古老的药物。

For millennia, doctors, caregivers, and healers had known that sham treatments made for happy customers. Thomas Jefferson himself marveled at the genius behind the placebo. “One of the most successful physicians I have ever known has assured me that he used more bread pills, drops of colored water, powders of hickory ashes than of all other medicines put together,” Jefferson wrote in 1807. “It was certainly a pious fraud.”

数千年来,医生,护士还有牧师们都意识到善意的谎言能使患者快乐。汤姆森·杰弗逊为安慰剂背后的天才想法而感到惊讶。‘我认识的一位着名的心理学家信誓旦旦的向我说他用过的面包药丸,色素水,核桃药粉比其他药物加起来都要多。很明显,对患者而言,这是一个善意的谎言’ —杰弗逊1807。

These days, placebo — Latin for “I shall please” — is much more than a pious fraud.

如今,安慰剂,即拉丁语中的‘我会好起来的’ 不仅仅是一个善意的谎言。

As Ted Kaptchuk at Harvard, who is regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on placebo, put it to me in a recent interview, the study of the placebo effect is about “finding out what is it that’s usually not paid attention to in medicine — the intangible that we often forget when we rely on good drugs and procedures. The placebo effect is a surrogate marker for everything that surrounds a pill. And that includes rituals, symbols, doctor-patient encounters.”

一位最顶尖的安慰剂专家,哈佛大学的托德·凯普查克最近接受了作者的访谈。安慰剂效果的研究既是‘寻找那些药品中我们不在意的或者经常忽略的无形之物。安慰剂效果就是个除了一个药丸本身以外的一切可能产生治疗效果的替代产物,包括程序,象征和医患关系’。

And it’s not just one thing. “I see the placebo effect as a kind of loose family of different phenomena that are just yoked together by this term,” says Franklin Miller, a retired NIH bioethicist who has edited a volume on the subject. “Sooner or later we’ll get rid of the term,” he says, and talk more specifically about each of its components.

这不是一个单纯的情况。退休的NIH (国家卫立研究院) 生物伦理学家佛兰克林·米勒在此课题做出了大量研究。他说:‘我认为安慰剂效果是松散且不精确的一类现象,只是被这个术语弄混在一起了。很快,我们将会废弃这个术语‘。

接着,他详细为作者介绍了每个细分成分。

The family of placebo effects ranges from the common sense to some head scratchers. Let’s start off with the simplest.

安慰剂效果分类范围下至最普通的感觉上至令人挠头皮的复杂事物。让我们从最简单的开始。

1) Regression to the mean

回归平均值

When people first go to a doctor or start on a clinical trial, their symptoms might be particularly bad (why else would they have sought treatment?). But in the natural course of an illness, symptoms may get better all on their own. In depression clinical studies, for instance, researchers find around one-third of patients get better without drugs or placebo. In other words, time itself is a kind of placebo that heals.

当人们第一次去找医生或者进行临床测试的时候,他们的症状可能非常糟糕(谁没病去找医生玩?)但是在疾病的自然过程中,症状可能会随着时间逐渐自身好转。在抑郁症临床测试例子中,研究员发现1/3的患者身体逐渐好转即使他们完全没接受任何治疗。换句话说,时间本身就是一种治疗安慰剂。

Sugar pills and active drugs can both change the way patients report symptoms.

糖丸和药品都能改变病人症状。

2) Confirmation bias

确认偏好

A patient may hope to get better when they’re in treatment, so they will change their focus. They’ll pay closer attention to signs that they’re getting better and ignore signs that they’re getting worse. (Relatedly, there’s the Hawthorne effect: We change our behavior when we know we’re being watched.)

一位病人可能希望得到康复当他在治疗过程中时。所以,他们会改变注意力并重点关注那些能康复的迹象同时忽略那些可能恶化的迹象。(内容相关,霍桑效应:当我们知道我们被关注的时候,我们会改变自身行为。)

But as we’ve seen, the placebo effect is more than just bias. There’s also:

但是,正如我们所看到的,安慰剂效果不仅仅是个偏好,它也是:

3) Expectations and learning

期望和学习

The placebo response is something we learn via cause and effect. When we take an active drug, we often feel better. That’s a memory we revisit and recreate when on placebo.

安慰剂反应是我们通过因果关系认识学习的。当我们使用了一个有效的药物,疾病会好转。而当我们服用安慰剂的时候,我们会再次体会或者再创造之前记忆中的疗效。

Luana Colloca, a physician and researcher at University of Maryland, has conducted a number of studies on this phenomenon. And they typically go like this: She’ll often hook up a study participant to an electroshock machine. For each strong, painful shock, she’ll flash a red light on a screen the participant is looking at. For mild shocks, she’ll flash a green light. By the end of the experiment, when the participants see the green light, they feel less pain, even when the shocks are set to the highest setting.

马里兰大学的内科医生兼研究员卢瓦纳·克洛卡对这一现象进行了一系列的研究。大致过程是:她经常在受验者身上使用电击器。高压电击时,她就在公共屏幕上显示红灯。一般电压的时候,就显示绿灯。在实验中发现,只要屏幕上是绿灯,受验者就觉得不疼即使电压是高压标准。

The lesson: We get cues about how we should respond to pain — and medicine — from our environments.

实验告诉我们:外界的诱因(如环境)会告诉我们如何对疼痛和药物产生与之相关的反应。

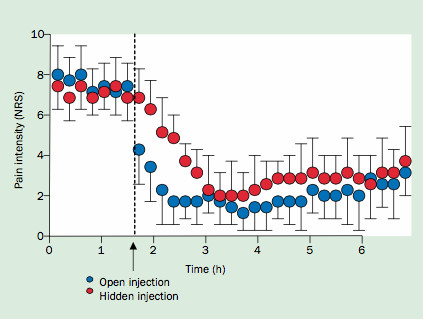

Take morphine, a powerful drug that acts directly on neurochemical receptors in the brain. You can become addicted to it. But its analgesic powers grow when we know we’re taking it, and know a caring professional is giving it to us.

吗啡,一种直接作用于大脑的中心神经系统的强力止痛药剂。而且会因此成瘾。但是当我们知道止痛药是吗啡并由专业人士提供时,止痛效果会显着提高。

Studies show that post-operative patients whose painkillers are distributed by a hidden robot pump at an undisclosed time need twice as much drug to get the same pain-relieving effect as when the drug is injected by a nurse they could see. So awareness that you’re being given something that’s supposed to relieve pain seems to impact perception of it working.

研究表明,术后那些被机器人分配止痛药的病人们往往需要两倍计量以上的止痛药才能与视觉上的体表注射药物的患者产生相同的止痛效果。所以呢,你的意识会因为你被提供某些止痛效果的东西而产生相对应的结果。

Pain relief is stronger and more immediate when morphine is injected out in the open. The Lancet Neurology

当开放注射吗啡的时候,止痛效果比隐藏注射更强更直接。-柳叶刀

The research also suggests that fake surgeries — where doctors make some incisions but don’t actually change anything — are an even stronger placebo than pills. A 2014 systematic review of surgery placebos found that the fake surgery led to improvements 75 percent of the time. In the case of surgeries to relieve pain, one meta-review found essentially no difference in outcomes between the real surgeries and the fake ones.

该研究还表明那些假手术-就是医生只在患者身上开个口子-甚至比安慰药物效果更强。2014年,一次外科安慰剂系统评估发现假手术75%的止痛效果依赖于时间因素。单在手术止痛效果方面上,综合分析假手术和真手术没有区别。

There is such thing as the nocebo effect: where negative expectations make people feel worse. Some researchers think this is what’s fueling the gluten-free diet fad. People have developed a negative expectation that eating gluten will make them feel bad. And so it does, even though they may not have any biological gluten sensitivity.

还有这样一件事,反安慰剂效应:即负面期望令人感到越来越糟糕。一些研究员觉得这是促进无麸质饮食的原因。因为大众就是认为麸质饮食是不好的,所以即使他们对麸质饮食不过敏,他们的身体也会排斥麸质饮食。

4) Pharmacological conditioning

药理学条件反射

This is where things get a little weird.

这是比较奇怪的地方。

Colloca has conducted many studies where for several days, a patient will be on a drug to combat pain or deal with the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Then one day, she’ll surreptitiously switch the patient over to a placebo. And lo and behold, they still feel healing effects.

克洛卡做了许多实验,在患者正常服用帕金森药物的流程中,突然有一天她偷偷把安慰剂给病人服用。结果却是病人依然觉得假药有效。

On that fifth day, it seems the placebo triggers a similar response in the brain as the real drug. “You can see brain locations associated with chronic pain and chronic psychiatric disease” acting like there are drugs in the system, she says. For instance, Colloca has found that individual neurons in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease will still respond to placebos as though they are actual anti-Parkinson’s drugs after such conditioning has taken place.

持续到第五天,安慰剂似乎令大脑产生了和真正药物相同的触发效果。她说:‘你可以发现在大脑与慢性疼痛和慢性精神疾病的相关区域’产生了和吃了真药的效果。举个例子,克洛卡发现即使当药品被这样替换之后,大脑中那些掌管帕金森疾病相关工作的独立神经元依旧能与安慰剂产生药品反应。

The brain can learn to associate taking a pill with relief, and produce the same brain chemicals when drug is replaced with placebo.

大脑可以学习药品与疾病的关联作用。即使该药品被替换为安慰剂,大脑依旧按照该药品的反应来分泌化学物质。

What’s going on here? Learning. Just like Pavlov’s dogs learned to associate the sound of a bell with food and would start to salivate in anticipation, our brains learn to associate taking a pill with relief, and start to produce the brain chemicals to kick-start that relief.

到底发生了什么?学习,就像巴普罗夫的狗把铃声和进食联系到一起一样,当铃声响起,狗就如期望中般的分泌唾液。我们的大脑把药丸和药效联系到一起,即使是安慰剂药丸,大脑也会分泌化学物质去推动药效。

This pharmacological conditioning only works if the drug is acting on a process that the brain can do naturally. “You can condition pain relief because there are endogenous pain-relieving mechanisms,” Miller says. Painkillers activate the opioid system in the brain. Taking a pill you think is a painkiller can activate that system (to a lesser degree).

药理学条件反射只建立在药品在大脑自然而然的产生作用。米勒说:‘你可以使疼痛减轻因为大脑有内部的疼痛减缓机制。止痛药在大脑中激活了鸦片类系统。随便一个你认为的止痛药丸都能激活这个系统(较小的程度上)

And some studies do suggest that the placebo effect’s powers may possibly move beyond the brain.

一些研究表明安慰剂效应的效果可能会胜过大脑。

Researchers have used flavored drinks to condition an immune response to placebo.

研究员利用调味饮料将免疫力反应与安慰剂相关联。

In a 2012 study, participants were given a sweet drink along with a pill that contained an immune suppressant drug for a few days. Without notice, the drug was swapped with placebo on one of the trial days. And their bodies still showed a decreased immune response. Their bodies had learned to associate the sweet drink with decreased production of interleukin, a key protein in our immune systems, which is produced in many cells outside the brain.

在2012年研究实验中,受验者得到甜饮和免疫力抑制药丸在开始几天里。在没有通知的情况下,药品被换成了安慰剂。然而他们的免疫力依旧在下降。因为身体已经把甜饮和白介素(重要的免疫系统蛋白质,产于到脑外的细胞)减少机制产生了关联。

Results like these show “we are talking about a neurobiological phenomenon,” Colloca says.

结果:‘我们需要考虑一些神经学现象了。’-克洛卡说

5) Social learning

社会学习

When study participants see another patient get relief from a placebo treatment (like in the electroshock experiment described above), they have a greater placebo response when they’re hooked up to the machine.

当受验员看到其他患者从安慰剂治疗(上述的电击测试)中获得效果时,并且也进行同样电击测试,他们会产生比前人更大的安慰剂反应。

6) A human connection

人际交流

Irritable bowel syndrome is an incredibly hard condition to treat. People with it live with debilitating stomach cramps, and there are few effective treatments. And doctors aren’t sure of the underlying biological cause.

大肠急躁症候群(IBS,个人理解就是拉肚子)是一个难以治疗的应激反应。患者一般都有抑制性胃痉挛而且几乎无药可医。医生们甚至不了解其生理病因。

It’s the type of ailment that’s sometimes derided as “all in their head,” or a diagnosis given when all others fail. In the early 2000s, Harvard’s Ted Kaptchuk and colleagues conducted an experiment to see if usually intangible traits like warmth and empathy help make patients feel better.

这一类疾病被称为“疑神疑鬼“ 或者没其他更好的诊断的凑数货。在20世纪早期,哈佛大学的托德·凯普查克和同事进行了一个实验去观察像同情和热情之类的外部情绪是否能令患者好转。

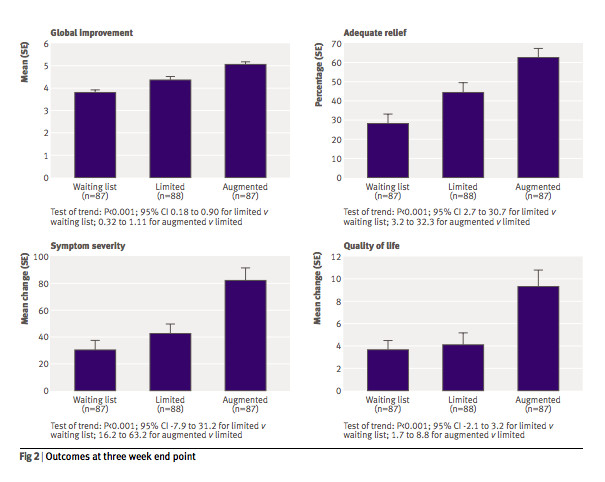

In the experiment, 260 participants were split into three groups. One group received sham acupuncture from a practitioner who took extra time asking the patient about their life and struggles. He or she took pains to say things like, “I can understand how difficult IBS must be for you.” A second group got sham acupuncture from a practitioner who did minimal talking. A third group was just put on a waiting list for treatment.

在这次试验中,260个参与人员被分为了三个组。A组接受假针灸疗法,同时医生花费更多时间去嘘寒问暖。工作人员怀着悲伤的心情对患者说:‘我能理解你必须承受的痛苦。’B组接受真的针灸治疗同时医生基本不与患者对话。C组患者只是记录名单并等待治疗。

A caring provider can create a stronger placebo response than an apathetic one.

一个热心的医生能比沉默寡言的医生创造更强的安慰剂反应。

The warm, friendly acupuncturist was able to produce better relief of symptoms. “These results indicate that such factors as warmth, empathy, duration of interaction, and the communication of positive expectation might indeed significantly affect clinical outcome,” the study concluded.

热心友善的医生能更有效地减轻症状。研究表明:三组结果为热心,同情,持续互动和乐观的交流能显着提升临床结果。

Participants in the “augmented” condition — the one in which the caregivers were extra attentive — reported better outcomes at the end of the three-week trial, compared with both participants who received treatment as normal and those waiting for treatment. BMJ

那些获得更多工作人员感情关照的参与者们比那些正常治疗的参与者和等待治疗的参与者明显获得了更好的治疗效果。-BMJ

This may be the least-understood component of placebo: It’s not just about pills. It’s about the environment a pill is taken in. It’s about the person who gave it to you — and the rituals and encounters associated with them.

这可能是安慰剂最难理解的部分了,安慰剂反应不仅仅在于是药丸,而是在于服用药丸的环境。在于给你药丸的人和相关的程序和遭遇。

What placebos can, and can’t, do

安慰剂能做什么和不能做什么。

Placebos seem to have the greatest power over symptoms that lie at the murky boundary between the physical and psychological.

其一,安慰剂似乎对介乎身体与心里的疾病有着超强的效果。

A 2010 systematic review looked at 202 drug trials where a placebo group was compared to patients who received neither placebo nor active drug. And it found that placebos seem to move the needle on pain, nausea, asthma, and phobias, with more inconsistent results for outcomes like smoking, dementia, depression*, obesity, hypertension, insomnia, and anxiety. (*Separate literature review on depression meds does find an effect of placebo compared with no treatment.)

2010年,系统评估了202例药物测试后,对比安慰剂组患者和不治疗的患者。我们发现安慰剂似乎对刺痛,恶心,哮喘和恐怖症有很大效果,对于吸烟痴呆,抑郁*,肥胖,高血压,失眠和焦虑,两组人员呈现了更不一致的结果。(*关于抑郁症药物的独立文献确是发现了安慰剂比不治疗有更大影响)

“It seems like placebo taps into a family of psychological and brain processes that’s very much something we evolved for,” says Tor Wager, a University of Colorado Boulder neuroscientist who has co-authored many of the key papers on the neuroscience of placebo. “Take pain as an example. If you step on something sharp, there’s pain in your foot. Now, how should you respond to it? Well, if you are running from an attack, you don’t even want to feel that. You keep going.”

曾合作发表了大量重大神经科系统学与安慰剂相关的论文的科罗拉多博尔德大学的的神经系统学家托儿·伟杰说:安慰剂就像一类进化非常多的心理和大脑进程。拿疼痛来举个例子。如果你驻足在锋利物的面前,你的脚可能会感到疼。好了,你会做出什么反应呢?再严重些的例子,你如果在逃离别人的攻击,你绝对不会回头。

Another way to think about it: Placebos tweak our experience of symptoms, not their underlying causes.

其二,需要思考的是:安慰剂只是曲解了我们对症状的理解而不是他们本身有疗效。

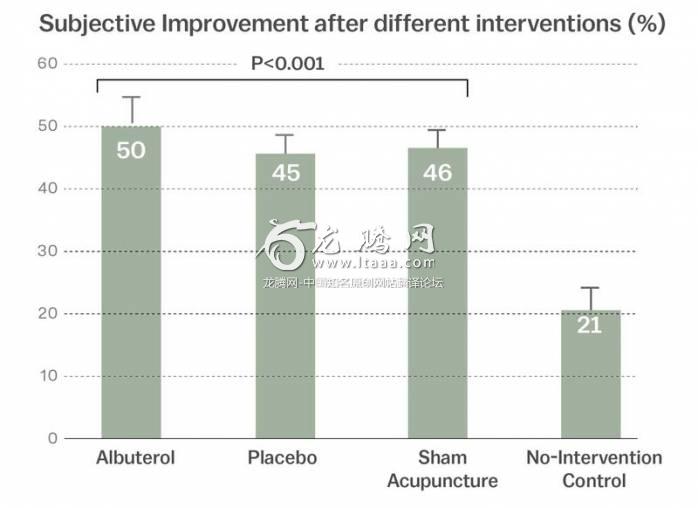

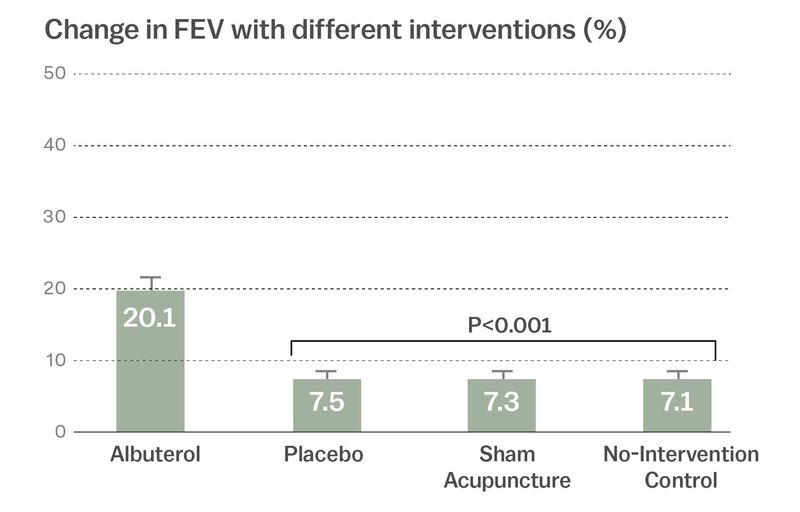

A 2011 study elegantly illustrates this. In the experiment, asthma patients were randomly sorted into three groups: One group received an inhaler with albuterol, a drug that opens the airways. Another group got an inhaler with a placebo. A third group got “sham” acupuncture (meaning the needles were withdrawn before they touched the skin). A fourth got nothing. The study authors uated lung function on two metrics: self-report from the patients on their asthma symptoms, and an objective measure of lung functioning.

2011年的一个实验优雅地解释了这个道理。在实验中,哮喘患者被随机分为三组:A组接收了舒喘灵(扩充气管)呼吸器。B组接收了假呼吸器。C组得到了‘假’针灸(就是做做样子,针完全不刺入皮肤)。D组啥都没有(谁啊?). 研究者以肺功能通过患者哮喘症状的自我汇报和肺功能客观测量作为评价指标。

If you go by self-report, it looks like the placebo, albuterol, and sham acupuncture are all equally effective.

如果你观察个人报告,三者都差不多有效。

The objective measure, however, shows only the albuterol improved airflow. (FEV is a measure of lung function.

然而在客观测量中,只有舒缓灵提升了肺部吸气量。(FEV 是肺功能测试方法)

Which isn’t to say that the self-reported improvement on placebo doesn’t matter. In many illnesses, patients would love a greater opportunity to ignore their symptoms.

这并不是指个人报告本身毫无意义,一些其他疾病中,主观的个人报告会有利于治疗。

“In all the objectively measurable illnesses, like cancer, even heart disease, there are components of it that are not [objectively measurable],” Kaptchuk says. And it’s those symptoms that are the prime targets to treat with placebo.

凯普查克说:在所有能客观测量的疾病中,如癌症甚至心脏病,依旧有一些细小的症状无法测量。而这些症状就是安慰剂的首要目标。

Placebo can only help symptoms that can be modulated by the mind. “There are real limits to what you can condition,” Miller says. You can’t, for example, condition the cancer-killing effects of chemotherapy. Our bodies don’t produce cancer-killing chemicals.

安慰剂只能通过调节心理活动来治疗症状。米勒说:‘这是有很多限制条件的,比如你不能调节你的身体产生物质去限制癌细胞杀伤力,因为身体就不存在那种化学物质‘。

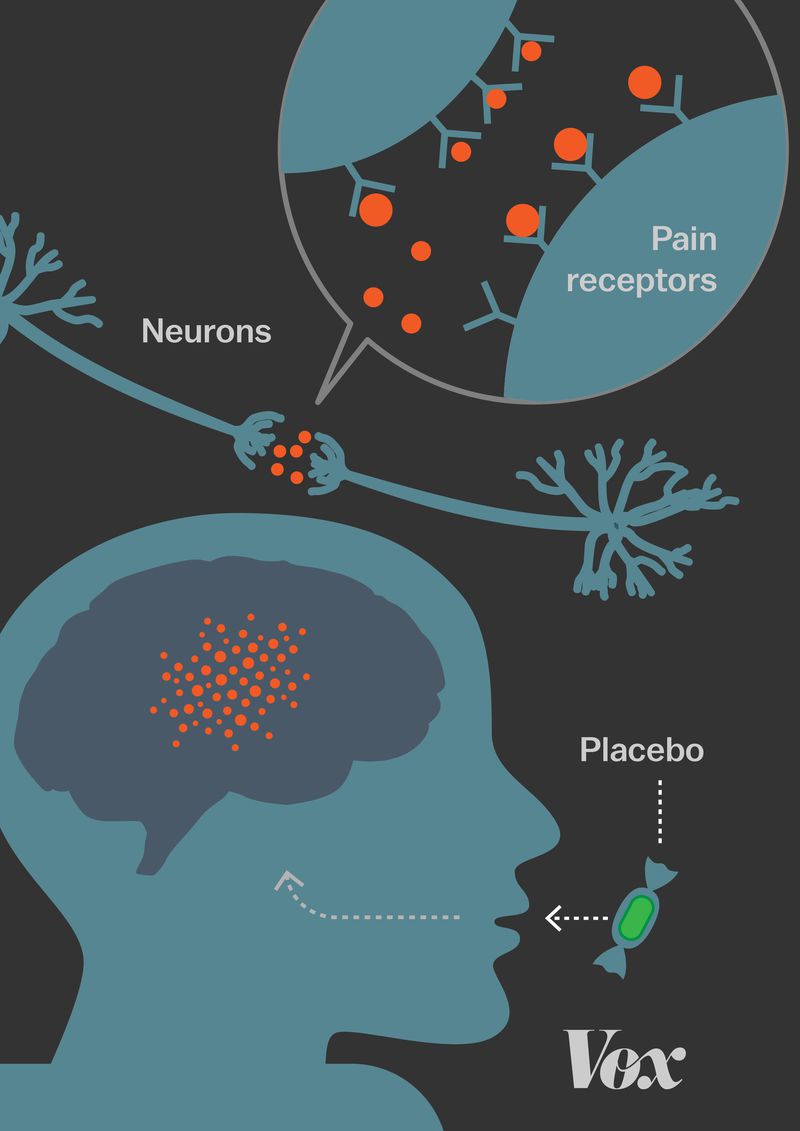

There’s evidence that placebos actually release opioids in the brain

有证据表明安慰剂释放了大脑中的鸦片类物质。

Over the past 15 years, scientists have made some of their most interesting discoveries looking at how placebos have a powerful impact on the brain.

在过去15年之间,科学在研究如何安慰剂影响大脑的领域上得到了很多有趣的发现

“When I first started studying placebo effects, it kind of seemed like magic — for some reason, your brain mimicked a drug response,” Wager says. “The biggest change in this field in the last 15 years is that neuroscientists are beginning to uncover the underlying neural mechanisms that create the placebo response.”

伟杰说:当我第一次去研究安慰剂效应时,我发现它如同魔法一般使你的大脑模仿药物的作用。安慰剂领域这15年来最大的变化是神经系统学家开始揭开安慰剂反应潜在的自然机制的面纱。

Placebos, researchers have found, actually prompt the release of opioids and other endorphins (chemicals that reduce pain) in the brain. Other findings:

研究人员发现安慰剂实际上促使大脑释放鸦片类物质和内啡肽(止痛物质)

其他发现:

●Drugs that negate the effects of opioids — such as naloxone — also counteract the placebo effect, which shows that placebos are indeed playing on the brain’s natural pain management circuitry.

抑制鸦片类物质的药品(如纳洛酮-吗啡拮抗药)会抵消安慰剂效应。这表明安慰剂确实作用于大脑自身的疼痛管理电信号系统。

●The periaqueductal gray matter, a region of the brain key for pain management, shows increased activity under placebo. Regions of the spinal cord that respond to pain show decreased activity under placebo, which suggests either the sensation of pain or our perception of it is diminished under placebo.

脑部疼痛管理的关键区域-中脑导水管周围灰质 表明安慰剂增加了该位置的大脑活动。反应疼痛的脊髓区域反而受到了抑制。这表明在安慰剂的影响下,我们对疼痛的感觉或者知觉减弱了。

●Patients with Alzheimer’s disease start to show a diminished placebo response. It’s probably due to the degradation of their frontal lobes, the area of the brain that helps direct our subjective experience of the world.

阿尔茨海默病患者则显示安慰剂反应减弱了。可能是因为他们大脑额叶的退化。大脑额叶区域帮助大脑管理对外界的个人感觉。

Our understanding of all this is far from complete, Wager says. For one, researchers still don’t completely understand how the brain processes pain. A lot of the brain regions implicated in the placebo response also play a role in emotions. So we don’t yet know if placebo is actually reducing our sensation of pain, or just our interpretation of it. (Also, as with a lot of neuroscience studies, a brain area might “light up” in an experiment, but it’s really, really hard to know what exactly is going on.)

伟杰说:我们还对此了解的还远远不够,比如研究员依旧不能完全理解大脑如何处理疼痛。太多的大脑区域涉及安慰剂反应而且影响情绪。所以,我们目前为止还是不知道安慰剂到底是减弱我们疼痛的感觉还是我们对疼痛的解读(同样的,就神经系统研究而言,实验中大脑活跃了一片区域,但是依旧无法理解大脑到底发生了什么)

“So really, what we should be concluding from those studies is something like ‘placebo affects the pain you report,’” Wager says. “What does pain mean to you? That’s a decision that’s made in your brain in different circuits, and that’s essential to placebo.”

‘真的,我们真的应该得到安慰剂效应能影响你疼痛的结论吗?疼痛对于你到底意味着什么?这个由大脑各路信号汇总的答案就是安慰剂的本质。‘

You can tell people they’re taking a sugar pill for their illness, and they’ll still feel better

你可以告诉人们他们实际上在用糖丸治疗疾病,但是他们依旧觉得病情好转了。

Kaptchuk has studied the placebo effect for decades, and something always bothered him: deception. Placebo studies have long relied on double-blind procedures. It ensures scientific rigor but keeps patients in the dark about what they’re actually taking.

凯普查克研究了数十年安慰剂效应了,有一些事一直困扰着他:就是欺骗。安慰剂研究长时间依靠双盲试验。虽然它确保了科学上的精确,但是却让患者瞎琢磨他们到底吃了啥。

“About five years ago, I said to myself, ‘I’m really tired [of] doing research that people say is about deception and tricking people,’” he says.

他说:我在五年前告诉我自己,我真厌倦了这些欺骗和欺诈的研究。

So he wanted to see: Could he induce a placebo response even when he told patients they were on placebo?

所以,他想看到如果他告知患者他们服用的是安慰剂而不是药品,安慰剂是否还能产生效果?

His own randomized controlled trials found that giving patients open-label placebos — sugar pills that the doctors admit are sugar pills — improved symptoms of certain chronic conditions that are among the hardest for doctors to treat, including irritable bowel syndrome and lower back pain. And he wonders if chronic fatigue — a hard-to-define, hard-to-treat, but still debilitating condition — will be a good future target for this research.

他主导的随机对照实验发现患者服用开放标签的安慰剂后(就是专业医生认证并贴条的糖丸)确实能改善类似于大肠激躁症,下背痛等特别难治愈的慢性应激病。而且他想知道是否慢性疲劳症候群这种特别难定义,难治疗且令人衰弱的疾病将会是安慰剂的新研究方向。

“Our patients tell us it’s nuts,” he says. “The doctors think it’s nuts. And we just do it. And we’ve been getting good results.”

‘我们的患者认为我们疯了,其他医生认为觉得我们傻了,但我们做了而且成功了。

Kaptchuk’s work adds a few new mysteries to the placebo effect. For one, he says that the placebo effect doesn’t require patient expectations for a positive outcome to work. “All my patients are people who have been to many doctors before. They don’t have positive expectations about getting better,” he says. “They’ve been to 10 doctors already.”

凯普查克的研究为安慰剂效应增加了新的神秘要素。比如他说安慰剂效应不需要病人对疗效积极的期望。他说:‘我的所有病人试验前都见过一堆医生了,他们已经没有啥太多的念想了,至少都见过10个。‘

Colloca has a different interpretation of his results. She says there’s a difference between belief and expectation, so while the patients may not believe the pill will work, they still unconsciously expect it to.

克洛卡对他的研究有着不同的解释,她认为尽管他的病人信仰和期望有高有低,即使他们知道药丸没用。但是他们来了,在他们内心中依然无意识的希望安慰剂能治病。

That’s because, she says, they still have a deep-seated conditioned memory for what it means to take a pill. They have a conditioned memory for what it means to be in the care of another person. And that memory is indeed an expectation that can kick-start the analgesic effect in the brain. They don’t have to be aware it’s happening.

这是因为这些病人对药丸有着深层条件记忆。即当被他人照顾时,条件记忆被激活。这个记忆是一个确实的期望并促使大脑产生止痛效果,尽管他们并没有意识到这件事。

Some doctors wonder if placebos can be integrated into mainstream medicine

一些医生希望了解安慰剂能否被纳入主流医学。

The researchers I spoke to for this story are overall optimistic that these discoveries can be used in the clinical settings. There’s a lot of work left to do here, and certainly some of the findings are easier to implement than others. For instance, we could start with reminding doctors that they can relieve pain simply by being warm and caring to their patients.

文中出现的这些研究员们都是很乐观的,他们认为他们的发现可以被用于临床环境中。当然他们有很多工作要做,不过有一些发现是很容易去在临床实施的。比如医生们可以通过嘘寒问暖来减少病人的疼痛。

Colloca wonders if the placebo effect can also be harnessed so that the millions living with chronic pain can feel the same therapeutic effects with a lower dosage of opioid treatments that are both ineffective and deadly.

克罗克想知道是否能使用安慰剂效应配合低剂量的鸦片类药品来使得数以百万的慢性疼痛疾病患者感到和正常剂量鸦片类药物(不能根治且致死)相同的治疗效果。

The NIH’s Miller says it’s too soon to start prescribing placebos, or using the effect, to decrease the dosage of a drug. For one, most of these studies are short-term and conducted with healthy volunteers, not actual patients.

NIH 员工米勒说临床使用安慰剂还是有点早,不管是把安慰剂当药,还是单纯的利用其效应,亦或是配合其他药物使用。举个例子,大多数研究都有待长期观察而且实验人员都是健康的志愿者并不是真的病人。

“There’s still lot we don’t know,” he says. Like side effects: Just as a placebo can mimic a drug, it can also mimic a side effect. “We haven’t done the kinds of studies that will indicate that you can maintain therapeutic benefit at lower side effect burden.”

他说:我们依旧有太多东西需要去探索。比如药物副作用。正如安慰剂能够模仿药物疗效,它也能模仿副作用。我们没做过这样的副作用研究,不清楚安慰剂能否保持相同疗效的情况下还能降低副作用。

More broadly, Kaptchuk says, for years researchers have seen the placebo as a hurdle to clear to produce good medicine. But placebo is not just a hurdle. “It’s basically the water that medicine swims in,” he says. “I would like to see the bottom line of my research change the art of medicine into the science of medicine.”

更宽广的未来,凯普查克说:多年来,一些研究员把安慰剂当作了生产好药的障碍(估计是双盲实验)。但其实不是,这就如同鱼与水之间的关系,安慰剂是一种非常基础且不可或缺的药品理论。他希望能看到他们研究的安慰剂技术最终演变为一门新的医学学科。(提前祝贺医科未来本硕博连读)

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8803653/drink.jpg)