大西洋月刊:科学的认知有极限吗? [美国媒体]

我们可以探测到黑洞,但是我们仍然不能治愈普通的感冒。阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦说过:“宇宙中最令人费解的事情是它是可以理解的。”他的确有理由感到惊讶。人类的大脑进化出了适应性,但我们的基本神经结构几乎没有改变,因为我们的祖先曾在大草原上游荡,应对着生活中所出现的挑战。这些大脑让我们能够理解量子和宇宙的意义......

Is There a Limit to Scientific Understanding?

科学的认知有极限吗?

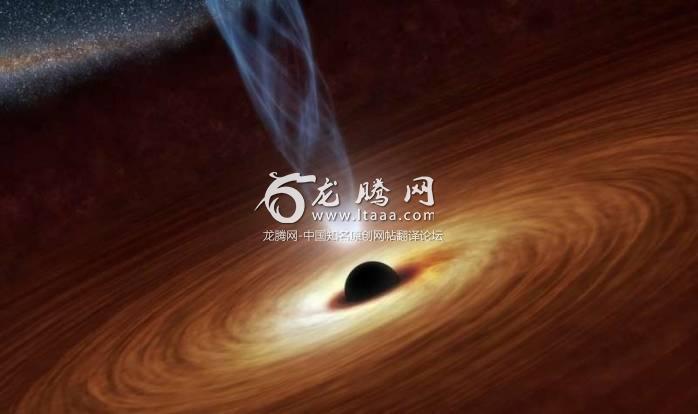

We can measure black holes, but we still can't cure the common cold.

我们可以探测到黑洞,但是我们仍然不能治愈普通的感冒。

Albert Einstein said that the “most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.” He was right to be astonished. Human brains evolved to be adaptable, but our underlying neural architecture has barely changed since our ancestors roamed the savannah and coped with the challenges that life on it presented. It’s surely remarkable that these brains have allowed us to make sense of the quantum and the cosmos, notions far removed from the “commonsense,” everyday world in which we evolved.

阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦说过:“宇宙中最令人费解的事情是它是可以理解的。”他的确有理由感到惊讶。人类的大脑进化出了适应性,但我们的基本神经结构几乎没有改变,因为我们的祖先曾在大草原上游荡,应对着生活中所出现的挑战。这些大脑让我们能够理解量子和宇宙的意义——这些远离了我们在其中进行进化的日常世界和常识,这是非凡的一件事。

But I think science will hit the buffers at some point. There are two reasons why this might happen. The optimistic one is that we clean up and codify certain areas (such as atomic physics) to the point that there’s no more to say. A second, more worrying possibility is that we’ll reach the limits of what our brains can grasp. There might be concepts, crucial to a full understanding of physical reality, that we aren’t aware of, any more than a monkey comprehends Darwinism or meteorology. Some insights might have to await a post-human intelligence.

但我认为科学会在某个时间点触礁。有两个原因可能会导致这一点成真。其中较为令人乐观的一点是:我们对某些领域(如原子物理学)的清扫和整理已经到了没有更多内容可说的地步。第二个原因可能更令人担忧:我们将会达到我们的大脑所能理解的极限。可能有一些概念对我们彻底理解物理现实是至关重要的,但也是我们没有意识到的,其程度就如猴子对达尔文主义或气象学的理解一样。一些见解可能需要留待人类之后的智慧生命来开启。

Scientific knowledge is actually surprisingly “patchy”—and the deepest mysteries often lie close by. Today, we can convincingly interpret measurements that reveal two black holes crashing together more than a billion light-years from Earth. Meanwhile, we’ve made little progress in treating the common cold, despite great leaps forward in epidemiology. The fact that we can be confident of arcane and remote cosmic phenomena, and flummoxed by everyday things, isn’t really as paradoxical as it looks. Astronomy is far simpler than the biological and human sciences. Black holes, although they seem exotic to us, are among the uncomplicated entities in nature. They can be described exactly by simple equations.

科学知识实际上处于令人惊讶的“零散”状态——而最深的奥秘往往就位于我们身旁。今天,我们可以令人信服地解释用于揭示两个在距离地球超过10亿光年的地方相撞的黑洞的探测方法。但与此同时,尽管已经在流行病学方面取得了巨大的进步,但我们在治疗普通感冒方面却进展甚微。事实上,我们可以自信于了解神秘和遥远的宇宙现象,却会对日常事物感到不可思议,这并不像看上去的那么矛盾。天文学比生物和人类科学要简单得多。黑洞虽然对我们来说是奇异的,但却是自然界中简单的实体之一。它们可以用简单的方程式来进行描述。

So how do we define complexity? The question of how far science can go partly depends on the answer. Something made of only a few atoms can’t be very complicated. Big things need not be complicated either. Despite its vastness, a star is fairly simple—its core is so hot that complex molecules get torn apart and no chemicals can exist, so what’s left is basically an amorphous gas of atomic nuclei and electrons. Alternatively, consider a salt crystal, made up of sodium and chlorine atoms, packed together over and over again to make a repeating cubical lattice. If you take a big crystal and chop it up, there’s little change in structure until it breaks down to the scale of single atoms. Even if it’s huge, a block of salt couldn’t be called complex.

那么我们该如何定义复杂性呢?科学究竟能走多远,这在一定程度上取决于这个答案。由几个原子组成的物质不会很复杂。宏观事物也不一定会是复杂的。尽管体量巨大,但一颗恒星却是相当简单的——它的核心是如此的热,以至于复杂的分子被撕裂,没有化学物质存在,所以剩下的基本上是一种由原子核和电子组成的无定形气体。或者,想想看一种由钠和氯原子组成的盐晶体,它们一个个地垒在一起,形成一个循环往复的立方体晶格。如果你将一个大的晶体切成小块,它的结构几乎没有变化,直到分解成单个原子的大小。即使一块盐体是巨大的,它也不能被称为复数。

Atoms and astronomical phenomena—the very small and the very large—can be quite basic. It’s everything in between that gets tricky. Most complex of all are living things. An animal has internal structure on every scale, from the proteins in single cells right up to limbs and major organs. It doesn’t exist if it is chopped up, the way a salt crystal continues to exist when it is sliced and diced. It dies.

原子和天文现象——这些非常小和非常大的现象都是非常基本的。但是居于它们中间的每一件事去都显得很微妙。最复杂的是生物。每一种动物都有其内部结构,从单个细胞的蛋白质到四肢和主要器官。如果它被切掉,它就不存在了,而当盐晶体被切成碎片或碎粒的时候,它还会继续存在。但是生物就会死去。

Scientific understanding is sometimes envisaged as a hierarchy, ordered like the floors of a building. Those dealing with more complex systems are higher up, while the simpler ones go down below. Mathematics is in the basement, followed by particle physics, then the rest of physics, then chemistry, then biology, then botany and zoology, and finally the behavioral and social sciences (with the economists, no doubt, claiming the penthouse).

科学的认知有时被设想成一种等级制度,它就像建筑物的地板一样有序。那些处理复杂系统的科学位于更高层级,而处理较简单系统的科学则位于较低层级。数学位于地下室,然后是粒子物理学,然后是物理学,然后是化学,然后是生物学,然后是植物学和动物学,最后是行为和社会科学(毫无疑问,经济学家们声称他们处于顶层公寓)。

“Ordering” the sciences is uncontroversial, but it’s questionable whether the “ground-floor sciences”—particle physics, in particular—are really deeper or more all-embracing than the others. In one sense, they clearly are. As the physicist Steven Weinberg explains in Dreams of a Final Theory (1992), all the explanatory arrows point downward. If, like a stubborn toddler, you keep asking “Why, why, why?” you end up at the particle level. Scientists are nearly all reductionists in Weinberg’s sense. They feel confident that everything, however complex, is a solution to Schr?dinger’s equation—the basic equation that governs how a system behaves, according to quantum theory.

给科学“排序”是没有争议的,但是“底层科学”——特别是粒子物理学——是否真的比其他学科更深入或者更全面?这是值得怀疑的。从某种意义上说,它们显然是。正如物理学家史蒂文·温伯格在《最终理论的梦想》 (1992)中所解释的那样,所有的阐释箭头都指向了下方。就像一个固执的孩子一样,如果你不停地问“为什么,为什么,为什么?”你最终会触及到粒子的层次。在温伯格看来,科学家几乎都是简化论者。他们相信,无论多么复杂,一切都是薛定谔的等式的解决方案——根据量子学理论,这是一个基本的方程式,它统治着一个系统的行为。

But a reductionist explanation isn’t always the best or most useful one. “More is different,” as the physicist Philip Anderson said. Everything, no matter how intricate—tropical forests, hurricanes, human societies—is made of atoms, and obeys the laws of quantum physics. But even if those equations could be solved for immense aggregates of atoms, they wouldn’t offer the enlightenment that scientists seek.

但是一个简化论者的解释并不总是最好的或者最有用的。物理学家菲利普·安德森说:“更多就是不同。”所有的一切,无论多么错综复杂——比如热带森林、飓风、人类社会——但它们都是由原子构成的,遵循量子物理学定律。但是,即使这些方程式能够被聚合在一起的大量原子所解决,它们也无法提供科学家们所寻求的启示。

Macroscopic systems that contain huge numbers of particles manifest “emergent” properties that are best understood in terms of new, irreducible concepts appropriate to the level of the system. Valency, gastrulation (when cells begin to differentiate in embryonic development), imprinting, and natural selection are all examples. Even a phenomenon as unmysterious as the flow of water in pipes or rivers is better understood in terms of viscosity and turbulence, rather than atom-by-atom interactions. Specialists in fluid mechanics don’t care that water is made up of H2O molecules; they can understand how waves break and what makes a stream turn choppy only because they envisage liquid as a continuum.

包含大量粒子的宏观系统表现出“突现”的特性,这些特性在与这一系统级别相适应的新的、不可约的概念上得到了最好的理解。原子价、原肠胚形成(当细胞在胚胎发育过程中开始分化)、铭记机制和自然选择都是例子。即使是像管道中或河流中的水流那样并不神秘的现象,也能通过粘度和湍流的概念——而不是原子间的相互作用——得到更好的理解为。流体力学的专家并不关心水是由水分子构成的;他们能够理解海浪是如何断裂的,以及是什么使河流变得波涛汹涌,这仅仅是因为他们把液体看作是一种连续体。

New concepts are particularly crucial to our understanding of really complicated things—for instance, migrating birds or human brains. The brain is an assemblage of cells; a painting is an assemblage of chemical pigment. But what’s important and interesting is how the pattern and structure appears as we go up the layers, what can be called emergent complexity.

新概念对于我们对复杂事物的理解尤其重要——例如,迁徙的鸟类或人类的大脑。大脑是细胞的集合;绘画是一种化学颜料的集合。但重要和有趣的是当我们进入到更上层层级的时候,模式和结构是如何出现的,它们就是所谓的突现复合体。

So reductionism is true in a sense. But it’s seldom true in a useful sense. Only about 1 percent of scientists are particle physicists or cosmologists. The other 99 percent work on “higher” levels of the hierarchy. They’re held up by the complexity of their subject, not by any deficiencies in our understanding of subnuclear physics.

所以的简化论在某种意义上都是正确的。但在有用的意义上,它却很少是正确的。只有大约1%的科学家是粒子物理学家或宇宙学家。其他99%的人都在“更高”的层次上工作。他们被他们的学科的复杂性——而不是我们对亚核物理学的理解的缺陷——所阻碍。

In reality, then, the analogy between science and a building is really quite a poor one. A building’s structure is imperiled by weak foundations. By contrast, the “higher-level” sciences dealing with complex systems aren’t vulnerable to an insecure base. Each layer of science has its own distinct explanations. Phenomena with different levels of complexity must be understood in terms of different, irreducible concepts.

在现实中,科学与建筑之间的类比确实是相当糟糕的。建筑物的结构因地基不佳而受到威胁。相比之下,处理复杂系统的“高层次”科学并不容易受到不安全的基础的攻击。每一层科学都有自己独特的阐释体系。必须用不同的、不可约的概念来理解具有不同层次复杂性的现象。

We can expect huge advances on three frontiers: the very small, the very large, and the very complex. Nonetheless—and I’m sticking my neck out here—my hunch is there’s a limit to what we can understand. Efforts to understand very complex systems, such as our own brains, might well be the first to hit such limits. Perhaps complex aggregates of atoms, whether brains or electronic machines, can never know all there is to know about themselves. And we might encounter another barrier if we try to follow Weinberg’s arrows further down: if this leads to the kind of multidimensional geometry that string theorists envisage. Physicists might never understand the bedrock nature of space and time because the mathematics is just too hard.

我们可以期待在三个前沿领域取得巨大进展:非常微观的领域、非常宏观的领域和非常复杂的领域。然而,当我却把我的脖子伸出到这些领域的时候,我的预感是:我们所能理解的东西是有限度的。理解非常复杂的系统,比如我们自己的大脑,可能是第一个达到这种极限的研究领域。也许复杂的原子聚合体——无论是大脑还是电子仪器——永远都不可能知道所有关于它们自身的信息。如果我们继续沿着温伯格的箭头走下去,我们可能会遇到另一个障碍:如果它导致了弦理论学家设想的多维几何形态的话。物理学家可能永远都无法理解空间和时间的基本性质,因为数学太难了。

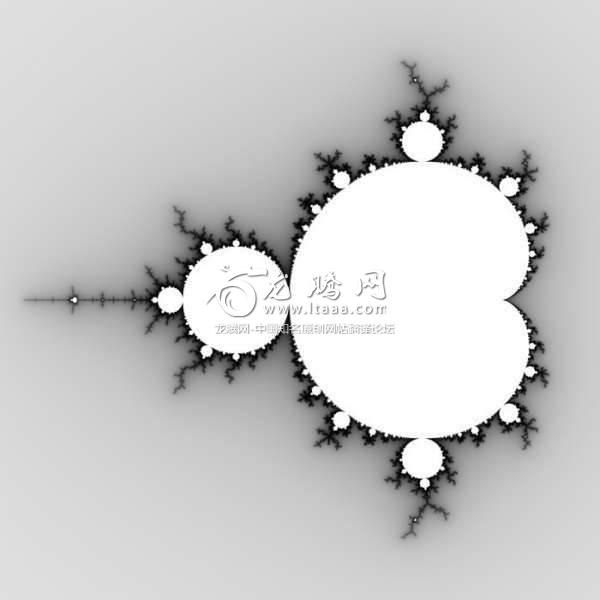

My claim that there are limits to human understanding has been challenged by David Deutsch, a distinguished theoretical physicist who pioneered the concept of “quantum computing.” In his provocative and excellent book The Beginning of Infinity (2011), he says that any process is computable, in principle. That’s true. However, being able to compute something is not the same as having an insightful comprehension of it. The beautiful fractal pattern known as the Mandelbrot set is described by an algorithm that can be written in a few lines. Its shape can be plotted even by a modest-powered computer:

我的观点是人类的理解是有限制的,但这一观点已经受到了David Deutsch的挑战,他是一位杰出的理论物理学家,他开创了“量子计算”的概念。在他的极具煽动性的优秀着作《无限的开端》 (2011)一书中,他说道:从原则上讲,任何过程都是可以计算的。这是真的。然而,能够计算出某些东西并不等同于对它有深刻的理解。被称为曼德勃罗集合的漂亮分形图像是由一种可以几行写完的算法描述出来的。它的形态甚至可以用一台只拥有中等计算力的计算机来绘制:

A Mandelbrot set (Flickr / Dominic Alves)

一个曼德勃罗集合

But no human who was just given the algorithm can visualize this immensely complicated pattern in the same sense that they can visualize a square or a circle.

但是,没有一个人能够仅仅通过给出这个算法就把这个非常复杂的图案想象出来,就像他们可以想象出一个正方形或者一个圆一样。

The chess champion Garry Kasparov argues in Deep Thinking (2017) that “human plus machine” is more powerful than either alone. Perhaps it’s by exploiting the strengthening symbiosis between the two that new discoveries will be made. For example, it will become progressively more advantageous to use computer simulations rather than run experiments in drug development and materials science. Whether the machines will eventually surpass us to a qualitative degree—and even themselves become conscious—is a live controversy.

国际象棋冠军卡斯帕罗夫在《深度思考》(2017年)中认为,“人类+机器”的组合比任何一个人都更强大。也许是通过利用两者之间强化的共生关系,新的发现将会被创造出来。例如,在药物开发和材料科学上使用计算机模拟而不是进行实验将会越来越有优势。这些机器是否最终会超越我们,达到质变的程度,甚至连自己都变成了一种意识——这是一场正在进行的争论。

Abstract thinking by biological brains has underpinned the emergence of all culture and science. But this activity, spanning tens of millennia at most, will probably be a brief precursor to the more powerful intellects of the post-human era—evolved not by Darwinian selection but via “intelligent design.” Whether the long-range future lies with organic post-humans or with electronic superintelligent machines is a matter for debate. But we would be unduly anthropocentric to believe that a full understanding of physical reality is within humanity’s grasp, and that no enigmas will remain to challenge our remote descendants.

生物大脑的抽象思维为所有文化和科学的出现提供了支撑。但是,这场跨越了数万年的活动,很可能只是人类之后的更强大智慧生物的短暂先驱——这些智慧生物将不是通过达尔文物种选择理论进化而来的,而是通过“智能设计”而产生的。远期的未来是否取决于有机的后人类智慧生物,还是电子超级智能机器,这是一个值得争论的话题。但我们还是会过度地以人类为中心,相信对物质实相的全面理解尽在人类的掌握之中,不会有任何谜团会留下来挑战我们遥远未来的后代。

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10