[大西洋月刊] 气候变化会导致更多的战争吗? [美国媒体]

一篇新发表的论文质疑称越来越多的证据表明气候波动可以引发战争,但是研究人员怀疑它的价值。这是21世纪最重要的问题之一:气候变化是否会给两个原本和平的国家带来摩擦的火花,从而将它们推向战争?

Does Climate Change Cause More War?

气候变化会导致更多的战争吗?

A new paper questions the growing body of evidence that weather fluctuations can prompt wars, but researchers have doubts about its value.

一篇新发表的论文质疑称越来越多的证据表明气候波动可以引发战争,但是研究人员怀疑它的价值。

It’s one of the most important questions of the 21st century: Will climate change provide the extra spark that pushes two otherwise peaceful nations into war?

这是21世纪最重要的问题之一:气候变化是否会给两个原本和平的国家带来摩擦的火花,从而将它们推向战争?

In the past half-decade, a growing body of research—spanning economics, political science, and ancient and modern history—has argued that it can and will. Historians have found temperature or rainfall change implicated in the fall of Rome and the many wars of the 17th century. A team of economists at UC Berkeley and Stanford University have gone further, arguing that an empirical connection between violence and climate change persists across 12,000 years of human history.

在过去的五十年里,越来越多的研究——包括经济学、政治学、古代和现代历史方面的——都认为它既是可能的,也有着这种倾向。历史学家发现,在罗马衰落的过程中,以及17世纪的许多战争中,气温或降雨量的变化是有关联的。加州大学伯克利分校和斯坦福大学的一组经济学家更进一步,他们认为:暴力和气候变化之间的经验联系在12000年的人类历史中仍然存在。

Meanwhile, high-profile scientists and powerful politicians have endorsed the idea that global warming helped push Syria into civil war. “Climate change did not cause the conflicts we see around the world,” Barack Obama said in 2015, but “drought and crop failures and high food prices helped fuel the early unrest in Syria.” The next year, Bernie Sanders declared that “climate change is directly related to the growth of terrorism.”

与此同时,一些备受瞩目的科学家和影响力巨大的政界人士也支持了这样一种观点,即全球变暖推动了叙利亚陷入内战。奥巴马在2015年表示:“气候变化并没有造成我们在世界各地看到的冲突。但是干旱、粮食歉收和高昂的粮价助长加剧了叙利亚的早期动荡。”翌年,伯尼·桑德斯声称:“气候变化与恐怖主义的增加有着直接关系”。

If you live on a planet expecting changes to temperature or rainfall in the coming decades—which will come faster and stronger than the many natural climate changes of the past—it’s all a bit worrying. So a paper published Monday in Nature Climate Change might seem like a nice respite. After undertaking a large-scale analysis of more than 100 papers published on the topic, the article argues that the connections between climate change and war aren’t as strong as they seem—that the entire literature “overstates the links between both phenomena.”

如果你生活在一个预计未来几十年气温或降雨量会发生变化的星球上,而这种变化趋势将比过去的许多自然气候变化来得更快、更强——这一切都将令人担忧。因此,周一发表在《自然气候变化》杂志上的一篇论文似乎提供了一次不错的喘息之机。在对100多篇有关这一主题的论文进行了大规模的分析之后,文章认为气候变化与战争之间的联系并不像它们认为的那样强大——所有的文献都“夸大了这两种现象之间的联系”。

Phew, you might think, maybe things aren’t so bad.

你也许会想,事情并不是那么糟糕。

Except that—to hear scientists who study the issue tell it—the paper does not make its own case as strongly as it may seem at first. “I can’t see what the authors are trying to accomplish with this article,” says Elizabeth Chalecki, a political scientist at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

除了聆听研究这个问题的科学家们的论述之外,这篇论文并没有像它一开始似乎要做的那样强烈地提出自己的观点。“我不知道作者们想要用这篇文章来表达什么”,位于奥马哈的内布拉斯加大学的一名政治科学家Elizabeth Chalecki说道。

The paper arrives into a field deeply polarized between researchers who endorse a link between climate change and violence and those who reject one. For scholars who approve of the link, the paper doesn’t prove its point or even say much of anything new. And while researchers who rebuff the link are more charitable to the paper, they also do not think it throws the field’s most famous studies into question—because they already questioned the veracity of that work.

这篇论文涉及到了一个支持气候变化与暴力之间存在联系的研究者和反对这一观点的研究者之间出现两极分化的领域。对于那些赞成存在这种联系的学者来说,这篇论文并没有证明它的观点,甚至没有提出任何新的东西。虽然否认存在这一联系的研究人员对这篇论文更加宽容,但他们也不认为这篇文章会让该领域最着名的研究成果陷入质疑当中——因为他们已经在质疑了这项研究的真实性了。

“Some may read this paper as saying that there’s lots of literature that says climate change causes conflict, and that this literature is based on sampling errors,” says Jan Selby, a professor of international relations at the University of Sussex. “But even before this paper, there was huge disagreement about what links could be made between climate change and conflict. And irrespective of the question of sampling error, I think the evidence in many of those papers is really weak.”

“有些人可能会读到这篇文章,认为有很多文献指出气候变化会导致冲突,而这些文献却是基于错误的抽样撰写的”,苏塞克斯大学的国际关系教授Jan Selby说道,“但就在这篇论文发表之前,人们对于气候变化与冲突之间的联系仍然存在巨大分歧。不管是否存在抽样错误的问题,我认为很多论文中的证据都是很薄弱的”。

First, though, to the paper itself. The authors attempt a large-scale analysis of the entire field of conflict and climate-change research. To do this, they searched an enormous academic database for certain keywords—like climate, war, weather, and unrest—then pruned the thousands of articles that they found down to a slim 124 that substantively addressed the connection between the two topics. Then, they analyzed the resulting body of papers for the names of certain countries and regions.

首先,来说说论文本身。作者试图对整个冲突和气候变化研究领域进行大规模的分析。为了做到这一点,他们在一个庞大的学术数据库中搜索了一些关键字,比如气候、战争、天气和动荡,然后将他们找到的数千篇文章精简为124篇,这些文章实质上都致力于研究这两个问题之间的联系。然后,他们分析了一些国家和地区的名称,并对其结果进行了分析。

After running this analysis, the authors conclude that the entire field is biased in two ways: toward countries that are easy for English-speaking researchers to access, like Kenya and Nigeria; and toward countries where conflict has already erupted, like Syria and Sudan. They also say that the literature focuses too much on Africa, ignoring vulnerable countries in Asia and South America.

在进行了这一分析之后,作者得出结论,即整个研究领域存在着两种偏见:一是对讲英语的研究人员来说相对容易接触到的国家,如肯尼亚和尼日利亚;二是对那些已经爆发冲突的国家,比如叙利亚和苏丹。他们还说,这些文献过于关注非洲,忽视了亚洲和南美的脆弱国家。

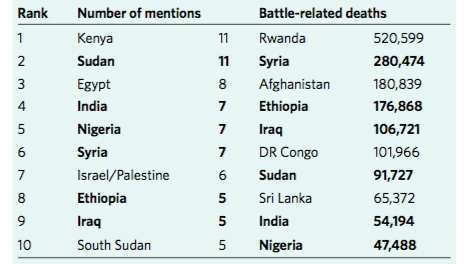

The countries that were mentioned most in the climate-conflict literature included Kenya, Sudan, Egypt, India, Iraq, and Israel and the Palestinian territories. (Though even the two most-mentioned countries, Kenya and Sudan, only appeared in 8.8 percent of all papers.)

在气候冲突文献中提到最多的国家包括肯尼亚、苏丹、埃及、印度、伊拉克、以色列和巴勒斯坦。(尽管肯尼亚和苏丹这两个被提及最多的国家在所有论文中仅占8.8%。)

That list shares very little overlap with a list of countries that should theoretically be the most vulnerable to climate change, which includes Rwanda, Honduras, Haiti, Myanmar, and the tiny Pacific island nation of Kiribati. But it is quite similar to a list of the countries that have suffered the most combat-related deaths in the last quarter-century.

这份名单与那些理论上最容易受到气候变化影响的国家的名单几乎没有重叠,这些国家包括卢旺达、洪都拉斯、海地、缅甸,以及太平洋岛国基里巴斯。但它却与过去25年里因为战争死亡人数最多的国家的名单非常相似。

In the Climate-Conflict Literature, the Most-Mentioned Countries Are Also the Most Recently Violent

在气候冲突文献中,提到最多的国家都是最近才发生暴力事件的国家

At left, the top countries that have been mentioned in the conflict-climate literature; at right, the countries that had the most battle-related deaths from 1989 to 2015. Countries that appear twice are in bold text. (Adams et al. / Nature Climate Change)

表格左侧是在冲突-气候文献中提到过的排名最靠前的国家;表格右侧则是1989年至2015年因为战争死亡人数最多的国家。出现两次的国家都是粗体表示。

“If we only look at places where violence is, can we learn anything about peaceful adaptation to climate change? And if we only look at those places where there is violence, do we tend to see a link because we are only focusing on the places where there is violence in the first place?” asked Tobias Ide, a coauthor of the paper and a peace and conflict researcher at the Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research.

该论文的合着者,同时也是奥格尔国际教科书研究所的和平与冲突研究员Tobias Ide问道: “如果我们只关注发生暴力的地方,那么我们能够了解到与和平适应气候变化相关的任何东西吗?”如果我们只关注那些有暴力的地方,我们是否会倾向于发现联系的存在,因为我们只关注了那些发生暴力的地方?”

He believes the study throws both the quantitative and qualitative research on the question into doubt. The qualitative research suffers from “the streetlight effect,” an overreliance on English-speaking former colonies in Africa where it is easier to do research, he says. (The “streetlight effect” refers to only looking for your keys—or anything else—where it’s easiest to see in the dark.) Quantitative research, he says, is ailed by “sampling on the dependent variable”: that is, only studying war in places where there is already war.

他相信关于这个问题的定量和定性研究都是有问题的。他说,定性研究受到了“路灯效应”的影响,它对非洲说英语的前殖民地存在研究上的过度依赖,因为在那里进行研究比较容易。(“路灯效应”指的你只会在黑暗中更容易看到的地方寻找你的钥匙或者其他任何东西。)他还指出,定量研究是通过“对相关变量的抽样调查”而得出的:也就是说,只研究那些已经发生战争的地区的战争。

Ide and many other researchers worry that such research will eventually harm the people that live in the places that are being studied. “In Sudan, Kenya, Syria, people say climate change is causing conflict, and that it will cause more conflict in the future because of droughts and stuff,” Ide said. “This scares investors away. People don’t want to invest there anymore because they’re scared these places are biased, or immature, or barbaric.”

Ide和许多其他研究人员担心,这样的研究最终会对生活在被研究地区的人们造成伤害。Ide说:“在苏丹、肯尼亚、叙利亚,人们说气候变化正在引发冲突,而且由于干旱和其他原因,未来将会导致更多的冲突。这将令投资者恐慌。人们不想再在这些地区投资了,因为他们害怕这些地方是有偏见的、不成熟的,或者是野蛮的”。

Ide also fretted that this will encourage Western philanthropists or militaries to unseat local power in these countries, in effect saying, “You can’t do it on your own, so we have to move in and manage your resources.”

Ide还担心,这将鼓励西方慈善家或军队在这些国家推翻当地的政权,实际上是说:“你不能自己做事,所以我们必须行动,来管理你们的资源。”

“I’m not saying that everyone who focuses on climate change in Syria or Kenya is automatically promoting colonial behavior, but if there’s a connective frame it might well facilitate this kind of thinking,” he told me.

他告诉我:“我并不是说所有关注叙利亚或肯尼亚气候变化的人都在自动地推动殖民行为,但如果存在着一个联系框架,它很可能会促进这种思维方式。”

Ide demurred when I asked where this kind of climate-science-driven colonialism has already happened. “If it comes to proving that a certain academic framing had an influence on people’s mind-set, or eventually even actions or policies, that’s really hard to pin down or prove empirically. People don’t just read academic studies—they watch television, they listen to peers,” he said. But he also said that the push to fortify southern Europe and adopt much more regressive immigration policies was driven, in part, by the climate literature.

当我问这种气候科学驱动的殖民主义是在什么时候发生的时,Ide提出了异议。“如果要证明某种学术框架对人们的思维方式造成了影响,或者最终甚至影响到了行动或政策,那就很难被证实或证明。人们不只是阅读学术研究,他们还看电视,他们还会听同龄人所说的言论。”但他也表示,推动南欧国家防御力量的努力,以及采取更加倒退的移民政策的做法,在一定程度上是由气候文献所推动的。

“From what I’ve heard from colleagues working on the issue, the idea that climate change is leading to conflict and migration in the Middle East—that is used by some conservatives and lobbyists and politicians in Brussels to inform stricter border controls in the south of the European Union, like not saving [refugees] in the Mediterranean Sea,” he told me. “It’s still anecdotal evidence, but it’s there.”

他告诉我:“据我从从事这一问题研究的同僚那里听说的说法,认为气候变化是导致中东地区冲突和迁移的观点正被布鲁塞尔的一些保守派、说客和政治家用来推动欧盟南部地区更严格的边境管制,比如不去拯救地中海地区(的难民)。这仍然是只是传闻中的证据,但它确实存在。”

His paper fits into a broader pattern of researchers—especially those in Europe—rejecting links between global warming and war. Selby, the Sussex professor, and a number of his colleagues published a blistering article last year attacking the idea that a climate-addled drought in any way pushed Syria into war. It argued that a prewar drought—which supposedly prompted the country’s economic chaos—was not as historically anomalous as claimed; and that the farmers who fled that drought had little involvement in the run-up to the war itself. He called the new article “a decent paper” without “obvious flaws.”

他的论文切合了那些更加广泛的研究者范式——尤其是那些身处欧洲的研究者——他们拒绝承认全球变暖与战争之间存在着联系。苏塞克斯大学的教授Selby以及他的一些同事去年发表了一篇文章,抨击了这样一种观点,即气候变化所导致的干旱让叙利亚陷入了战争之中。这篇文章认为,一场战前的干旱——它可能会引发该国的经济混乱——并不像之前所声称的那样具有历史上的反常波动;而那些逃离旱灾的农民几乎都没有参与到这场战争的准备阶段。他称这篇新发表的文章是“一篇没有明显缺陷的出色论文”。

“But I guess that’s probably to some extent because it confirms suspicions that I have anyway,” he said. He told me that there was “no consensus” in the quantitative literature on whether climate change exacerbates conflict. “Some people claim there is a consensus, but they only do so by ignoring a huge amount of literature and standing on what I think are spurious methodological grounds.”

他说:“但我认为在某种程度上这可能是因为它证实了我的怀疑。”他告诉我,关于气候变化是否会加剧冲突的定量文献中“没有产生共识”。“有些人声称这是一种共识,但他们只是忽略了大量其他的文献,并且持有我认为使用了虚假的方法论的立场”。

He said that conflict-climate scholars should study climate-vulnerable places where there has been no conflict as well as war zones. “If you go study in Costa Rica or Greenland, for example, then you will find a different correlation. And it will make the case as well.”

他说,冲突气候学者应该研究容易受气候影响、但是没有爆发冲突与战争的地区。例如,如果你去哥斯达黎加或格陵兰岛学习,你就会发现一种不同的相关性。这种状况也是时有发生的。”

“I don’t think there’s anything novel or particularly unusual in [the new paper],” says Simon Dalby, a professor of politics and climate change at the Balsillie School of International Affairs. “The focus on Africa—Africa, Africa, Africa, Africa—has been noted for years by those of us tracking this. And the ‘street lighting’ point is well taken. Kenya is easier to get into for lots of folks doing the research, who are mostly white-skinned Northerners who speak English,” he says.

“我不认为在这篇新发表的论文中有什么新颖或特别的东西”,巴尔西利国际事务学院的政治和气候变化教授Simon Dalby说道,“对非洲的关注多年来一直被我们这些跟踪这一问题的人所注意到。而‘路灯效应’的观点也被充分地采纳。肯尼亚更容易进入许多从事这项研究的人的视野当中,这些人大多是白皮肤的会说英语的北方人。”

Dalby takes something of a middle ground on the dispute. Going back to the 1990s, he says, a body of literature has “made it clear that environmental change might—in some complicated series of circumstances—lead to conflict, but it was the intervening circumstances that really mattered.”

Dalby在这场争端中站在了中间立场。他说,回到上世纪90年代,一批文献已经“清楚地表明在一些复杂的环境中,环境变化会导致冲突,但真正重要的是干预的环境。”

Another researcher who has harped on the focus on Africa is Solomon Hsiang, an economist and professor of public policy at UC Berkeley. In 2013, he and his colleagues noted the preponderance of Africa-focused research in a now-famous study that argued there was an empirical link between conflict and climate change. For every change of a standard deviation in temperature or rainfall, he and his colleagues found that the chance of violent conflict between groups rose by 14 percent.

另一位反复强调对于非洲的关注的研究人员是经济学家和加州大学伯克利分校的公共政策教授Solomon Hsiang。2013年,他和他的同事们注意到,在一项当前着名的研究中,非洲研究的优势主要集中在冲突与气候变化之间存在着的一种经验联系。他和他的同事们发现,在每一次气温或降雨量的标准偏差变化中,群体间暴力冲突的几率会上升14%。

“There is nothing really surprising or new in this study,” he said in an email. “Studying conflict-prone regions isn’t a problem, it’s what you would expect. Nobody is studying Ebola outbreaks by studying why Ebola is not breaking out in cafés in Sydney today, we study what happened in West Africa when there was an actual event.”

他在电子邮件中指出:“在这项研究中,没有什么是令人惊讶的,也没有什么是新鲜的。研究容易发生冲突的地区并不是问题所在,它正是你所期望的。没有人会通过研究埃博拉病毒在如今悉尼的咖啡馆里爆发的原因来研究埃博拉疫情,我们研究的是西非发生的真实事件。”

Hsiang also lambasted the article’s method of analyzing the literature as a whole to claim that researchers “[overstate] the links between” conflict and climate change.

Hsiang还抨击了这篇文章的分析方法,认为研究人员“夸大了冲突和气候变化之间的联系”。

“The biggest issue with the study is that they strongly insinuate there is some kind of bias boogeyman in the research field without actually showing that anybody else who came before made an error or demonstrating how their idea could affect findings in the field,” he told me. “They are vague and imprecise about their critique of prior work, without identifying which actual findings they are overturning or replicating anybody’s work. Instead, they simply allude to an aroma of a problem in the research field, which sows doubt without providing actual evidence.”

他告诉我:“这项研究最大的问题是,他们强烈地暗示称,研究领域存在某种偏见,而没有真正显示出之前的研究者犯下了错误,或者证明了他们的想法会对该领域的研究结果产生怎样的影响。他们对之前的工作的批评是模糊而不准确的,他们没有明确哪些发现是颠覆性的,而哪些只是照搬别人的成果。相反,它们只是暗示了研究领域存在的问题,在没有提供实际证据的情况下,这种暗示只会散播怀疑的情绪。”

The article itself appears to back off its claims by the end of the paper, saying that its findings are not intended to discredit any one researcher or study. “We are not saying that the correlations are invalid or invaluable, nor are we accusing any studies or authors who have focused on specific regions,” Ide told me. But the paper nonetheless claims that the conflict-climate link is overstated.

这篇文章最后似乎软化了它的主张,文章称调查结果并不是旨在诋毁任何一个研究者或研究成果。Ide告诉我:“我们并不是说这种关联性是无效或无价值的,我们也不会指责任何关注特定地区的研究成果或研究者”。但这篇论文还是声称冲突与气候之间的联系被夸大了。

Chalecki, the University of Nebraska political scientist, also finds the paper’s focus odd. It makes sense to study places where there is war, she says: “Violence isn’t an inherent condition in domestic politics or international politics. We don’t need to explain peace. It’s conflict, it’s war, that we need to explain.”

内布拉斯加大学的政治学家Chalecki也发现了这篇论文焦点的诡异之处。她说:“研究那些有战争的地方是有意义的。暴力并不是国内政治或国际政治的固有条件。我们不需要解释和平。冲突和战争才是我们需要解释的。”

She also wonders if the “streetlight effect” that preoccupied the authors was simply a tendency of academia, since authors tend to cite prior work on a topic. Academics focus on war zones because it matters how the war starts, she says. “In terms of policy-relevant research, I don’t think there is anything in this article that might help a country or region offset climate change,” she says. “If I’m talking to an undersecretary of defense, or a policy maker, they’re gonna look at this [paper] and say ... what does this even mean?”

她还想知道,作者所关注的“路灯效应”是否只是学术界的一种趋势,因为作者倾向于引用先前的研究课题。她说,学者们关注的是发生战争的地区,因为战争的爆发是很重要的。她说:“就政策相关的研究而言,我认为这篇文章里没有任何东西可以帮助一个国家或地区抵消气候变化的影响。”如果我是在和国防部副部长或政策制定者谈话,他们会在看过这篇文章然后说:这是什么意思?”

“I thought it was a weird article,” says Greg Petrow, another political scientist at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, who specializes in quantitative methods. He says the paper—which focuses on sampling bias in the field—suffered from sampling bias itself.

位于奥马哈的内布拉斯加大学的另一名政治学家Greg Petrow——他的研究领域是定量方法——说:“我认为这是一篇奇怪的文章”。他认为这篇论文——它关注于这一领域的抽样错误——本身就存在着抽样错误的问题。

“They’re not really directly assessing what they want to be assessing. They’re trying to assess sampling bias, but they’re looking at the sampling as a dependent variable. They’re actually looking at publication bias as an independent variable,” he says. There are papers that study publication bias, he added, but they don’t cite or refer to them.

他说:“他们并没有直接评估他们想要评估的东西。他们试图评估抽样错误,但他们将抽样作为了一种相关变量。他们实际上是把发表偏差作为了一个独立变量”。他还补充称,有一些研究发表偏差的论文,但是他们没有援引这些论文。

For Ide’s part, the paper shows how much more research on the topic can still be done. “I was a bit surprised that even within American studies, there’s not really a focus on Latin America, basically,” he said. “You can be concerned about Iraq, Syria, or India because of geopolitical relevance—but why not look for [climate-related conflict] in Mexico, or Honduras, or Brazil? Because that would have much sharper consequences for the United States.”

对Ide来说,这篇论文表明关于这个话题的更多研究仍然可以继续。他说:“我有点吃惊,即使在美国国内的研究中,基本上也没有真正关注拉丁美洲的人。你可以关注伊拉克、叙利亚或印度,这是因为地缘政治的相关性,但为什么不考虑在墨西哥、洪都拉斯或巴西寻找与气候相关的冲突呢?因为那样会对美国造成更严重的后果。”

And Dalby, the political scientist, tried to take a broader view of the dispute—and the climatic upheaval that could come later this century. “Looking for these empirical connections is all very well and good,” he told me, “but if you’re looking for the causes of climate change, it’s us—the overconsuming, fossil-fuel-burning North and West. If you want to get serious about climate change, worrying about the small-scale details of conflicts in Africa is missing the point. It’s us.”

而Dalby这位政治学家试图采用关于这场争论——以及在这个世纪出现的气候剧变——的更广泛的观点。他告诉我:“寻找这些经验性的联系是非常好的一件事,但如果你正在寻找导致气候变化的原因,原因就是我们自己——过度消费、北部和西部地区化石燃料的燃烧如果你想认真对待气候变化,担心非洲冲突的琐碎细节就没有意义了。问题就在于我们自己。”

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

Why do most people who have a positive view of China have been to ...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10