普华永道:机器人对英国就业的影响(上) [英国媒体]

我们的分析显示,英国多达30%工作岗位有很大的潜在风险被自动化技术替代,低于美国(38%)和德国(35%),但高于日本(21%)。一些行业的风险最高,比如运输与仓储(56%),制造业(46%)和批发零售业(44%),但另外一些行业风险偏低,比如医疗与社会工作(17%)。

4 – Will robots steal our jobs?

The potential impact of automation on the UK and other major economies[1]

机器人是否将抢走我们的工作?

自动化技术对英国及其他主要经济体的潜在冲击[注1]

Key points

摘要

. Our analysis suggests that up to 30% of UK jobs could potentially be at high risk of automation by the early 2030s, lower than the US (38%) or Germany (35%), but higher thanJapan (21%).

我们的分析显示,英国多达30%工作岗位有很大的潜在风险被自动化技术替代,低于美国(38%)和德国(35%),但高于日本(21%)。

. The risks appear highest in sectors such as transportation and storage (56%), manufacturing (46%) and wholesale and retail (44%), but lower in sectors like health and social work (17%).

一些行业的风险最高,比如运输与仓储(56%),制造业(46%)和批发零售业(44%),但另外一些行业风险偏低,比如医疗与社会工作(17%)。

. For individual workers, the key differentiating factor is education. For those with just GCSE-level education or lower, the estimated potential risk of automation is as high as 46% in the UK, but this falls to only around 12% for those with undergraduate degrees or higher.

对就业者个人来说,关键的差别来自于教育。在英国,接受普通中等教育或者更低的人,估计被自动化技术替代的潜在风险高达46%,但是那些大学及以上学历的人风险只有12%左右。

. However, in practice, not all of these jobs may actually be automated for a variety of economic, legal and regulatory reasons.

然而在实践中,因为经济、法律以及政策法规等一系列的原因,并非所有的上述工作都真的会被自动化代替。

. Furthermore new automation technologies in areas like AI and robotics will both create some totally new jobs in the digital technology area and, through productivity gains, generate additional wealth and spending that will support additional jobs of existing kinds, primarily in services sectors that are less easy to automate.

更进一步的说,像人工智能和机器人这样的新自动化技术将会在数字技术领域创造一些全新的工作岗位,并且,因为生产率的提高,可以创造出额外的财富和花销,来支持更多现有行业的工作机会,主要是在服务业这种更难被自动化的行业。

. The net impact of automation on total employment is therefore unclear. Average pre-tax incomes should rise due to the productivity gains, but these benefits may not be evenly spread across income groups.

综上所述,自动化对于整体就业的冲击的净值难以计算。由于生产率的提高,税前平均工资将会上升,但是这些利益并不会在不同的收入阶层中平均分配。

. There is therefore a case for some form of government intervention to ensure that the potential gains from automation are shared more widely across society through policies like increased investment in vocational education and training. Universal basic income schemes may also be considered, though these suffer from potential problems in terms of affordability and adverse effects on the incentives to work and generate wealth.

因此,需要有某种形式的政府干预来确保各个社会阶层都能分享到自动化带来的潜在收益,比如制定政策加大对职业教育培训的投资。社会基本收入计划(G19注:社会福利)也应被考虑,虽然这在可承受性以及激励就业创造财富方面的负面作用(G19注:指政府有没有钱来搞福利,以及吃福利是否会让人没有动力工作)。

Introduction

简介

The potential for job losses due to advances in technology is not a new phenomenon. Most famously, the Luddite protest movement of the early 19th century was a backlash by skilled handloom weavers against the mechanisation of the British textile industry that emerged as part of the Industrial Revolution (including the Jacquard loom, which with its punch card system was in some respects a forerunner of the modern computer). But, in the long run, not only were there still many (if, on average, less skilled) jobs in the new textile factories but, more importantly, the productivity gains from mechanisation created huge new wealth. This in turn generated many more jobs across the UK economy in the long run than were initially lost in the traditional handloom weaving industry.

技术进步对工作岗位的冲击早已不是什么新现象了。最有名的例子,19世纪初的卢德分子抗议运动就是熟练手工纺织工人对于英国纺织工业机械化——后来演变成了工业革命的一部分(包括提花织机,其打卡系统在某种意义上是现代计算机的先驱)——的反击。但是,长期来说,不仅仅是在新型纺织厂里仍然有很多人工岗位(甚至普遍更加不需要技能),而且更重要的是,机械化后生产率的提升创造了巨大的财富。这在长期为英国经济的各个领域创造了比先前在传统手工纺织工业流失的岗位更多的工作机会。

The standard economic view for most of the last two centuries has therefore been that the Luddites were wrong about the long-term benefits of the new technologies, even if they were right about the short-term impact on their personal livelihoods. Anyone putting such arguments against new technologies has generally been dismissed as believing in the ‘Luddite fallacy’.

因此,两个世纪以来,标准的经济学观点认为,卢德分子错了。他们虽然看到了对于其个人生计的短期冲击,但是他们没有看到新技术带来的长期好处。任何人对新技术的类似争议都会被斥为相信“卢德悖论”。

However, over the past few years, fears of technology-driven job losses have re-emerged with advances in ‘smart automation’ – the combination of AI, robotics and other digital technologies that is already producing innovations like driverless cars and trucks, intelligent virtual assistants like Siri, Alexa and Cortana, and Japanese healthcare robots.

然而,最近几年,对技术导致工作流失的担心再次回潮,这一次是在现金的“智能自动化”的背景下,其结合了人工智能、机器人和其他数字技术,已经在制造创新产品如无人驾驶汽车和卡车,智能虚拟助手如Siri,Alexa和Cortana,以及日本医疗保健机器人。

While traditional machines, including fixed location industrial robots, replaced our muscles (and those of other animals like horses and oxen), these new smart machines have the potential to replace our minds and to move around freely in the world driven by a combination of advanced sensors, GPS tracking systems and deep learning, if not now then probably within the next decade or two. Will this just have the same effects as past technological leaps – short term disruption more than offset by long term economic gains – or is this something more fundamental in terms of taking humans out of the loop not just in manufacturing and routine service sector jobs, but more broadly across the economy? What exactly will humans have to offer employers if smart machines can perform all or most of their essential tasks better in the future[2]? In short, has the Luddite fallacy finally come true?

如果说传统机器,包括固定位置工业机器人,代替了我们的肌肉(以及代替了其他动物如马和牛);那么这些新的智能机器有可能会取代我们的头脑,依靠先进的感应器、全球定位系统和深度学习在世界上自由的走来走去,不是现在就是在下个十年二十年内。这造成的影响会与之前的技术革命一样吗,只是短期破坏,会被长期的经济收益所抵消?还是这次会更加极端,会把人类踢出局,不仅仅是制造业和常规服务业的工作,而是广泛影响经济的各个领域?如果未来智能机器能够更好的执行所有或者大多数人类可以执行的任务,那人类还能给企业主带来什么[注2]?简而言之,卢德悖论是否终于成真?

This debate was given added urgency in 2013 when researchers at Oxford University (Frey and Osborne, 2013) estimated that around 47% of total US employment had a “high risk of computerisation” over the next couple of decades – i.e. by the early 2030s.

这场讨论在2013年被赋予了额外的紧迫感,这一年牛津大学的研究者(弗雷和奥斯本)估计美国总就业数的47%将在接下来的几十年里——比如2030年代初——“有很高风险被计算机化”。

However, there are also dissenting voices. Notably, Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn (OECD, 2016) last year re-examined the research by Frey and Osborne and, using an extensive newOECD data set, came up with a much lower estimate that only around 10% of jobs were under a “high risk[3] of computerisation”. This is based on the reasoning that any predictions of job automation should consider the specific tasks that are involved in each job rather than the occupation as a whole.

然而,也有不同意见。尤其是阿恩茨,格雷戈里和齐拉(经合组织,2016)去年重新检视了弗雷和奥斯本的研究,使用经合组织的扩大的新数据组,得出了低得多的结果,只有10%的工作岗位“有很高风险被计算机化”[注3]。该结果基于这样的推断,即任何对于工作被自动化的预测,应该考虑每个职位中所包含的具体工作内容,而不是把这个岗位简单的按整个计算。

In this article we present the findings from our own analysis of this topic, which builds on the research of both Frey and Osborne (hereafter ‘FO’) and Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn (hereafter ‘AGZ’). We then go on to discuss caveats to these results in terms of non-technological constraints on automation and potential offsetting job creation elsewhere in the economy (though this is much harder to quantify).

在本文中,我们提出了我们自己对于该问题的分析结果,这建立在弗雷和奥斯本(以下简称为“FO”),以及阿恩茨,格雷戈里和齐拉(以下简称为“AGZ”)的研究之上。之后我们将不仅仅局限于技术的层面上来讨论这些结果所说明的问题,关于自动化替代以及潜在的此消彼长在其他经济领域创造出来的工作机会(当然这更加难以量化)。

The discussion is structured as follows:

提纲如下:

Section 4.1 What proportion of jobs are potentially at high risk of automation?

4.1 多大比例的工作有较高风险会被自动化替代?

Section 4.2 Which industry sectors and types of workers could be at the greatest risk of automation in the UK?

4.2 英国哪些行业和工作种类被自动化替代的风险最高?

Section 4.3 Why does the potential risk of job automation vary by industry sector?

4.3 为什么不同行业的工作被自动化替代的风险不同?

Section 4.4 How does the UK compare to other major economies?

4.4 英国与其他主要经济体比较如何?

Section 4.5 What economic, legal and regulatory constraints might reduce automation in practice?

4.5 什么样的经济、法律和政策约束可能会在实践中减少工作被自动化替代?

Section 4.6 What offsetting job and income gains might automation generate?

4.6 自动化能带来什么样的替代性的工作机会以及收入增长?

Section 4.7 What implications might these trends have for public policy?

4.7 对于公共政策来说这些趋势意味着什么?

Section 4.8 Summary and conclusions.

4.8 归纳与总结

Further details of the methodology behind our analysis in Sections 4.1-4.4 are contained in a technical annex at the end of this article, together with references to the other books and studies cited.

我们4.1章到4.4章中分析背后的研究方法的具体细节,在文末会有一个附件加以说明,并且列出了引用的书与研究。

4.1 – What proportion of jobs are potentially at high risk of automation?

多大比例的工作岗位有较高风险会被自动化替代?

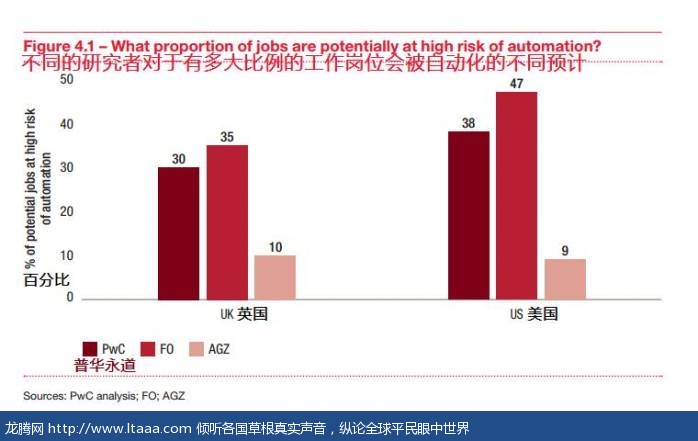

In the present article, we start by revisiting the sharply contrasting results of FO and AGZ, who estimate respectively that around 47% and 9% of jobs in the US, and around 35%[4] and 10% of jobs in the UK are at high risk of automation by, broadly speaking, the early 2030s (see Figure 4.1).

在前文中,我们回顾了FO和AGZ形成鲜明对比的结果,大约在2030年代早期,其分别预计美国有47%和9%,英国有35%[注4]和10%的工作岗位会被自动化替代(见图4.1)。

The AGZ study explains the difference as the result of a shift from the occupation-based approach of FO to the task-based approach adopted in their own study. In the original study by FO, a sample of occupations taken from O*NET, an online service developed for the US Department of Labour, were handlabelled by machine learning experts as strictly automatable or not automatable. Using a standardised set of features of an occupation, FO were then able to use a machine learning algorithm to generate a ‘probability of computerisation’ across US jobs, but crucially they generated only one prediction per occupation. By assuming the same risk in matching occupations, FO were also able to obtain estimates for the UK (other authors have also applied this approach to derive estimates for other countries).

AGZ的研究解释了这种不同,是把FO以职位为基础的算法转换为他们自己的以工作内容为基础的算法的原因。在FO的初始研究中,职位样本来自为美国劳工部开发的一个在线服务网站O*NET,被机器学习专家手动标注严格区分为可被替代和不可被替代。使用某个职位的一组标准特征,FO能够使用机器学习算法来算出美国工作岗位“被计算机替代的几率”,但关键的是他们对于一个职位只做一次预测。在假设相匹配的职位有相同的风险的基础上,FO也能够对英国作出预测(其他作者也采用了这种方法来推理预测其他国家的情况)。

AGZ argue, drawing on earlier research by labour market economists such as David Autor [5], that it is not whole occupations that will be replaced by computers and algorithms, but only particular tasks that are conducted as part of that occupation.

AGZ主张,借鉴劳动力市场经济学家如大卫奥托之前的研究[注5],并不是整个工作岗位会被计算机和计算程序代替,而只是一份工作中的部分特定的职能会被代替。

Furthermore, the same occupation may be more or less susceptible to automation in different workplaces. Using the same outputs from the FO study, AGZ conducted their analyses on the recently compiled OECD PIAAC database that surveys task structures for individuals across more than 20 OECD countries. This includes much more detailed data on the characteristics of both particular jobs and the individuals doing them than was available to FO.

此外,同一个职位在不同的工作场所被自动化技术影响的程度是不一样的。使用FO研究的结果,AGZ利用最近汇总的经合组织国际成人能力评估数据库进行了他们自己的分析,这个数据库调查了超过20个经合组织成员国的个人的工作内容体系。这要比FO的研究,在特定工作的特征和做这个工作的人的特征两方面都多了很多细节数据。

While recognising the differences in approach, it is still surprising that AGZ obtain results which differ so much from those of FO, bearing in mind that they started from a similar assessment of occupation-level automatability. We therefore conducted our own analyses of the same OECD PIAAC dataset as used in the AGZ study.

虽然可以看到在方法上的不同,但AGZ得到与FO差异如此之大的结果还是出人意料,要知道他们是从类似的针对职位层面的被自动化的评估开始的。因此我们使用与AGZ同样的经合组织国际成人能力评估数据库进行了我们自己的研究。

We first replicated the AGZ study findings, but then subsequently enhanced the approach through using additional data and developing our own machine learning algorithm for identifying automation risk[6]. Our findings offer some support for AGZ’s conclusion that taking into account the tasks required to be carried out within each worker’s occupation diminishes the proposed impact of job automation somewhat relative to the FO results. Nevertheless, we conclude that the particular methodology used by AGZ over-exaggerated this mitigating effect significantly.

我们先复制了AGZ研究结果,然后对方法进行了改善,通过使用额外的数据以及开发我们自己的机器学习算法来确定自动化的风险[注6]。我们的发现部分印证了AGZ的结论,即考虑到每份职位里需要执行的具体工作,略微降低了FO的结果中提出的工作自动化所带来的冲击。尽管如此,我们认为,AGZ使用的特定方法明显是过分夸大了这种降低的效果。

Specifically, based on our own preferred methodology, we found that around 30% of jobs in the UK are at potential high risk of automation and around 38% in the US. These estimates are based on an algorithm linking automatability to the characteristics of the tasks involved in different jobs as well as those of the workers doing them(e.g. the education and training levels required). Our estimates are somewhat lower than the original estimates by FO, but still much closer to those than to the 9-10% estimates of AGZ (see Figure 4.1).

具体而言,基于我们自己提出的方法,我们发现英国有30%的职位有潜在高风险被自动化,美国是38%。这一预计是建立在把自动化风险,与不同职位所包含的具体任务的特性以及做这些工作的人的情况(比如所需的教育与培训水平)相联系起来的程序算法基础上的。我们的评估结果略微低于FO创建的初始评估,但是与AGZ的9-10%的预计相比,还是更接近前者(见图4.1)。

Intuitively, the main reason for this is because the specific approach used by AGZ biased their results towards jobs having only a moderate risk of automation, but we found that this was more an artefact of their methodology than a true representation of the data (see Annex for more technical details of why we reach this conclusion).

直观的说,主要原因是AGZ所使用的某些方法使得他们的结果偏向于认为一些工作只有一些不太大的风险被自动化。但是我们发现他们的方法论更多的只是一个假象,而不是数据所真正代表的(我们为何得出这样的结论详见附件)。

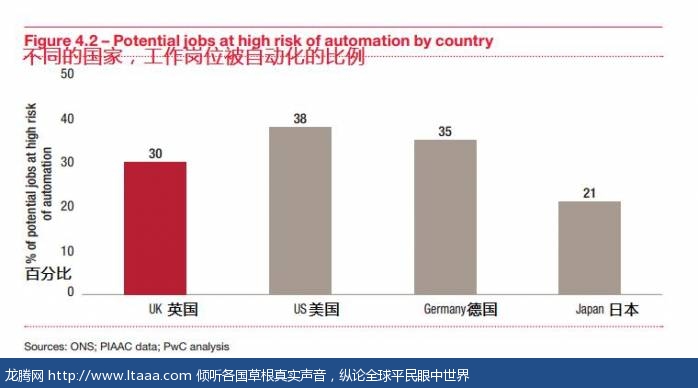

Our algorithm could also be applied to other OECD countries in the PIAAC database. For the purpose of the current article, we focus on the results for the UK, US, Germany and Japan[7]. We found that both the US and Germany have an increased potential risk of job automation compared to the UK, whilst Japan has a decreased potential risk of job automation (see Figure 4.2). These reasons for these differences are explore further in Section 4.4 below.

我们的计算方法同样适用于国际成人能力评估数据库中所包含的其他经合组织国家。基于本文的目的,我们专注于英国美国德国和日本的结果[注7]。我们发现美国和德国相对于英国来说在工作自动化方面存在更大的风险,然而日本的风险却较小(见图4.2)。这些差别的原因我们将在4.4章中进一步探讨。

Before exploring our results in more detail, we want to stress one important caveat that applies both to our results and those of FO and AGZ. This is that these are estimates of the potential impact of job automation based on anticipated technological capabilities of AI/robotics by the early 2030s. Not only is the pace of technological advance, and so the timing of these effects uncertain, but more importantly:

在探讨我们研究成果的具体细节之前,我们想做出一个重要的申明,对我们的以及FO和AGZ的研究都适用。即,这些是基于预期中的人工智能/机器人的技术能力,而对2030年代早期,工作自动化方面潜在的冲击作出的估计。不仅科学技术进步的步伐以及这些影响发生的时间点无法确定,更重要的是:

. not all of these technologically feasible job automations may occur in practice for the economic, legal and regulatory reasons discussed in Section 4.5 below; and

不是所有这些从技术角度看会发生的工作自动化,在经济运行、法律法规的约束下会全都真的发生,这在之后的4.5章中会讨论;并且

.even if these potential job losses do materialise, they are likely to be offset by job gains elsewhere as discussed in Section 4.6 below – the net long-term effect on total human employment could be either positive or negative.

即使这些潜在的工作岗位流失真的发生了,也有可能会被其他地方新增的就业机会所抵消,这将在之后的4.6章中讨论——长期来看对人类总体就业的影响可能是正面的也可能是负面的。

Unfortunately, it is much more difficult to quantify the effects of these caveats, particularly at the industry level, in part because the second one involves new types of jobs being created that do not even exist now. In contrast, we can try to quantify and analyse the number of jobs at potential high risk of automation by country, industry sector and type of worker as discussed below. But, in interpreting these results, we should never lose sight of these two key caveats.

不幸的是,以上两点的影响更加难以进行量化,尤其是在行业层面,因为在某种程度上第二条涵盖了将来会被创造出来的工作岗位在现在甚至根本不存在。相比之下,我们可以(相对容易的)尝试按照国别、行业和工种来分析和量化哪些工作有较高风险被自动化。但是,在分析这些结果时,我们不应忘记以上两点申明。

4.2 – Which industry sectors and types of workers could be at the greatest potential risk of automation in the UK?

英国哪些行业和工种被自动化替代的风险最高?

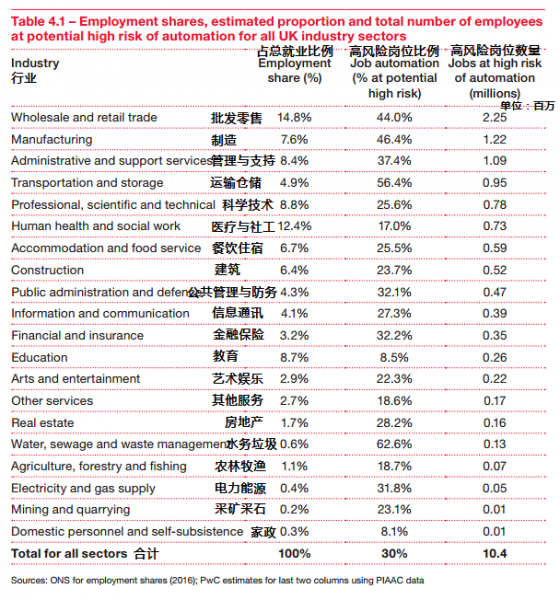

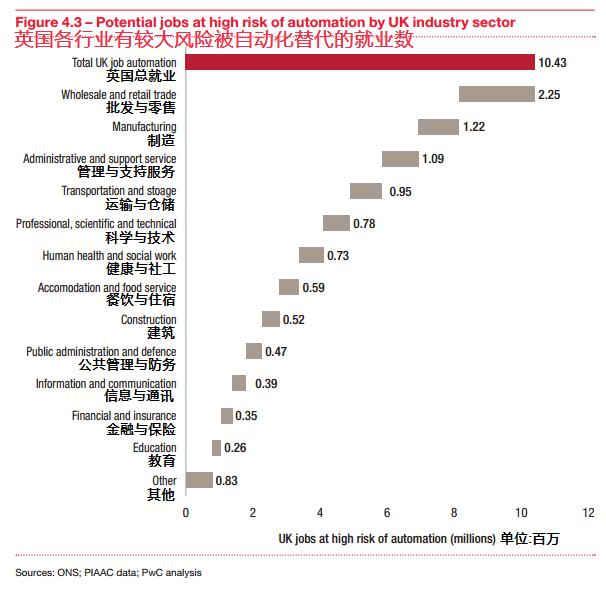

If, for the sake of illustration, we apply our 30% estimate from the previous section to the current number of jobs in the UK[8], then we might conclude (subject to the caveats noted above) that several million jobs could potentially be at high risk of automation in the UK. Broken down by industry, over half of these potential job losses are in four key industry sectors: wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing, administrative and support services, and transport and storage (see Table 4.1 and Figure 4.3 for details).

如果为了说明,我们把前一章所预估的30%乘以现在英国的职位数[注8],我们可以得出结论英国有几百万个岗位有很高风险会被自动化替代。分解到行业,一半潜在的工作损失会出现在四个主要行业:批发与零售贸易,制造业,管理与支持服务,以及运输及仓储(详见表4.1和图4.3)。

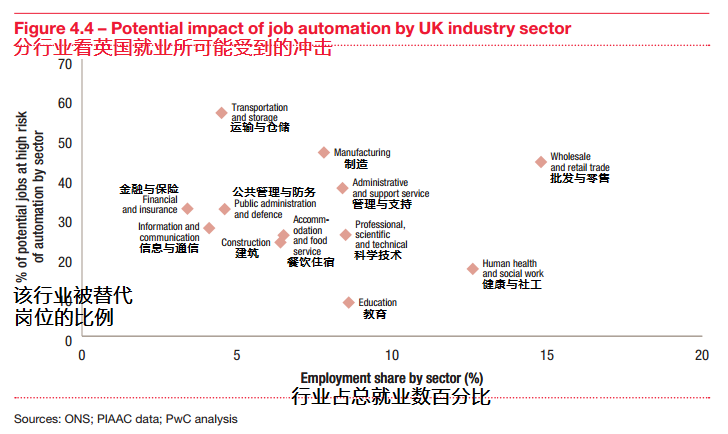

The magnitude of potential job losses by sector is driven by two main components: the proportion of jobs in a sector we estimate to have potential high risk of automation, and the employment share of that sector (see Figure 4.4 and Table 4.1). The industry sector that we estimate could face the highest potential impact of job automation is the transportation and storage sector, with around 56% of jobs at potential high risk of automation. However, this sector only accounts for around 5% of total UK jobs, so the estimated number of jobs at potential high risk is around 1 million, or around 9% of all potential job losses across the UK.

一个行业工作流失的量级由两个要素决定:我们所估算的该行业岗位被自动化替代的比例,以及该行业在总就业中所占的份额(见图4.4和表4.1)。受冲击最大的行业是运输与仓储,我们估计会有56%的岗位有很高风险。然而,这个行业的就业数在英国就业总数里只占5%,所以实际流失的职位数大概在一百万左右,或者说英国总工作流失的9%。

Instead the highest potential impact on UK jobs is in the wholesale and retail trade sector, with around 2.3 million jobs at potential high risk of automation (22% of all UK jobs estimated to be at high risk) given that this is the largest single sector in terms of numbers of employees. Manufacturing has a similar proportion of current jobs at potential high risk (46%), but lower total numbers at high risk of around 1.2 million due to it being a smaller employer. A further 0.7 million jobs could be at potential high risk of automation in human health and social work, but this is a much lower proportion of all jobs in that sector (around 17%).

真正的大头,是批发与零售贸易行业,会有约二百三十万个岗位有潜在高风险被自动化(占英国总就业流失的22%),这是从岗位数来说受影响最大的一个行业。制造业有着类似的流失风险(46%),但因为这个行业雇员数相对少些,所以受影响的岗位总数也少一些约为一百二十万个。健康与社会工作会有70万个岗位受影响,但这占本行业岗位总数的比例很低(约17%)。

Which types of UK workers may be most affected by automation?

英国什么工种受自动化影响最大?

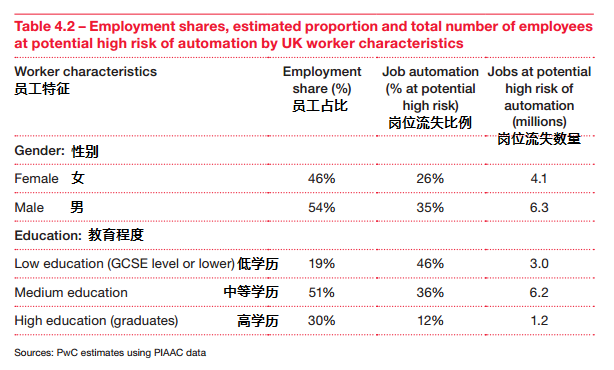

The potential impact of job automation also varies according to the characteristics of the workers. On average, we find that men and, in particular, those with lower levels of education (GCSE-level and equivalent only orlower) are at greater risk of job automation. This is characteristic of the sectors that are at highest estimated risk. For example, the transportation and storage, manufacturing, and wholesale and retail trade sectors have a relatively high proportion of low education employees (34%, 22%, and 28% respectively). Men also make up the great majority of the workforce in the first two of these sectors (85% and 73%).

影响的大小,也因工作者的不同特征而不同。平均来说,我们发现男性,尤其是低学历的男性(普通中等教育或者更低)其工作被自动化的风险更大。这也是那些风险最大的行业的特征。举例来说,交通与运输,制造,批发与零售贸易行业,相对来说低教育水平的员工比例更高一些(分别为34%,22%,和28%)。男性也构成了第一个和第二个行业的员工的主体(85%和73%)。

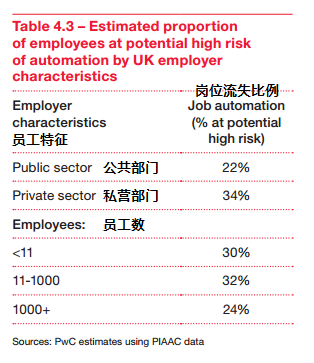

We also estimate that private sector employees and particularly those in SMEs are most at risk, which is linked to variations in job and employee characteristics (e.g. education and training levels required).

我们同时估计,私营企业雇员尤其是那些中小企业的雇员风险最大,这与工作的变动与员工的特征有关(例如所需的教育与培训水平)。

4.3 – Why does potential risk of job automation vary by industry sector?

为什么不同行业的工作被自动化替代的风险不同?

Task composition

任务结构

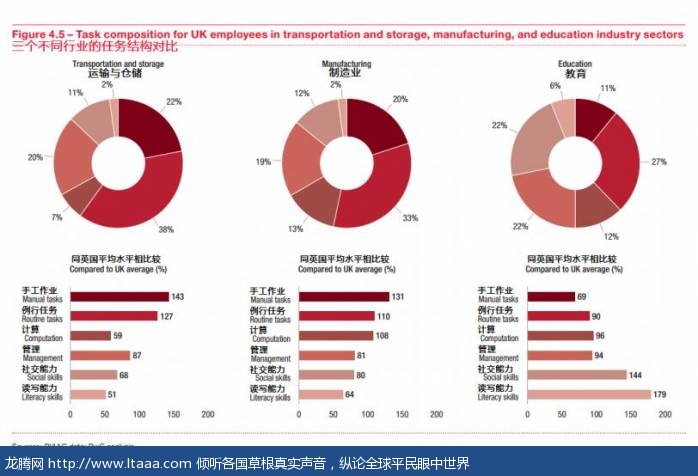

One of the main drivers of a job being at potential high risk of automation is the composition of tasks that are conducted. Workers in high automation risk industries such as transport and manufacturing spend a much greater proportion of their time engaged in manual tasks that require physical exertion and/or routine tasks such as filling forms or solving simple problems. In contrast, in lower automation risk industries such as education, there is an increased focus on social and literacy skills, as shown in Figure 4.5, which are relatively less automatable9.

使得一个岗位有高风险被自动化替代的驱动器之一,是其所执行的任务的结构。那些在被自动化替代风险很高的行业工作的人们,比如交通和制造业,工作时会进行更多的体力劳动和手工作业;或者进行重复性的例行任务,比如填表和解决简单的问题。与之对比,自动化风险较低的行业如教育,更加专注于社交和读写能力,见图4.5,相对更难被自动化替代。

Worker and job characteristics

工作者与职业特征

Task composition of jobs is not, however, the only driver of high automation risk. In the two largest sectors by employment share - wholesale and retail trade and human health and social work - there are broadly comparable task compositions (see Figure 4.6). However, the proportion of jobs at potential high risk of automation is over 2.5x greater in the wholesale and retail trade (44%) than for health and social work (17%).

但是,一份工作的任务结构并不是其被自动化替代的唯一驱动器。在就业人数最多的两个行业——批发与零售贸易,以及医疗与社会工作——两者大体来说有着近似的任务结构(见图4.6)。然而,前者有高风险被自动化替代的岗位比例(44%) ,超过后者 (17%)的2.5倍。

Instead differences in job requirements are the main factors that cause the risk of automation to differ between these two sectors, mostly significantly as regards education.

并非任务结构,而是这两个行业有不同岗位要求,才是造成两者被自动化替代的风险大相径庭的原因,其中最显而易见的是教育水平。

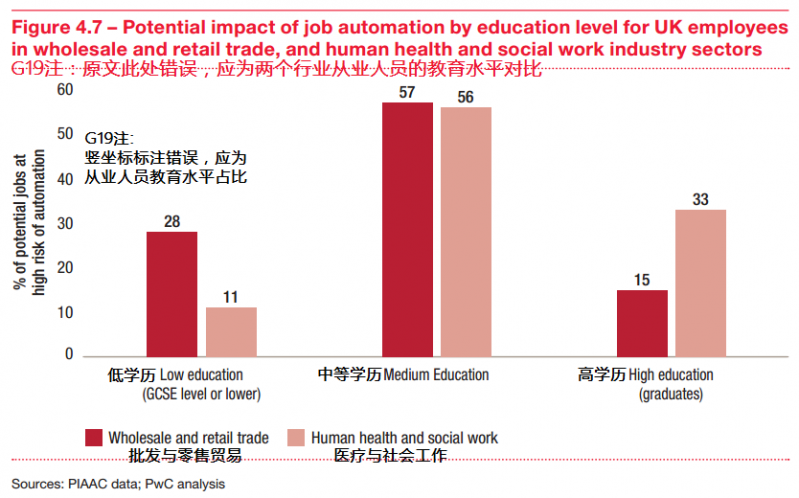

On the whole, education requirements are higher in the human health and social work sector, with more than twice the proportion of employees having high education levels (i.e. degree level or higher): 33% compared with 15% in wholesale and retail. Health and social work also has much lower proportions of low education workers (i.e. GCSE level or lower): 11% compared with 28% in wholesale and retail (see Figure 4.7).

整体来说,医疗与社会工作对教育水平的要求更高,接受过高等教育(大学或以上学历)者占比33%超过批发零售业15%的两倍。同时从事医疗与社会工作的低学历(职业教育及以下)者比例11%也明显低于批发与零售行业的28%(见图4.7)。

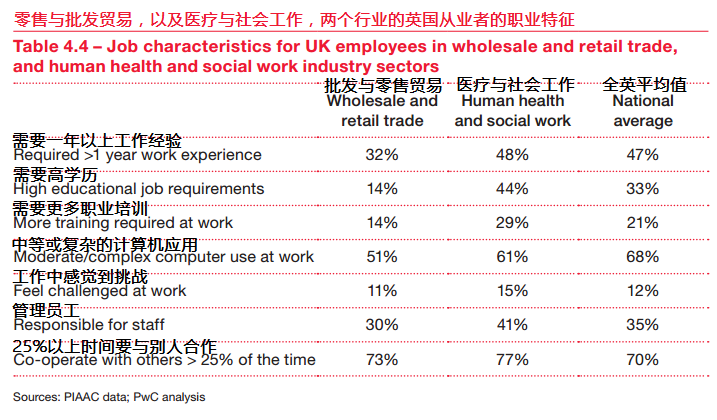

The difference in education levels is also reflected in the job characteristics for employees in the health and social work sector. There is a much higher proportion of employees that need work experience prior to employment, have higher educational requirements in their current role, and are engaged in more training at work (see Table 4.4).

教育水平的不同也反映在医疗与社会工作的职业特征上。有更高比例的员工在被雇佣前要求有工作经验,其现有岗位有更高的学历要求,并且参加更多的职业培训(见表4.4)。

A more detailed examination of the occupations in both sectors also reveals that a higher proportion of occupations in health and social work are jobs that are far less automatable than in wholesale and retail trade. In particular, sales workers that comprise the majority of employment share in the wholesale and retail trade sector have twice the job automation potential (38%) compared with personal care workers in the human health and social work sector (18%).

进一步细节化的检视两个行业的岗位,也显示出医疗与社会工作的岗位,远比批发与零售贸易行业难以被自动化替代。尤其是,构成后者主体的销售员工,相比前者中的医务工作者,有着两倍以上的风险被自动化替代(38%对18%) 。

The human health and social work sector also has a high proportion of employees (23%) in health professional or health associate professional occupations, which have particularly low automation potential according to our methodology. Advances we have seen in recent years in Japan in healthcare robots might suggest some of these model estimates could prove too low as this technology develops further and spreads to the UK, although some of these may be working with rather than replacing human workers. Similarly surgeons may be able to conduct operations remotely now using digitally controlled robotics, but (at least for the moment) we are some way from robot surgeons carrying out operations unaided.

医疗与社会工作行业还有较高比例(23%)的岗位,根据我们的方法论,被替代的风险特别低,那就是专业医生。虽然我们看到近些年在日本,出现了先进的医疗机器人,随着这种技术进一步发展以及传播到英国,可能会让我们的模型估算的风险显得过低;但是这些技术有可能是与人类一起工作,而不是替代人类。类似的外科医生可能可以数控机器人实施相似的手术,但是(至少现在)我们距离机器人独立实施手术还有一段距离。

4.4 – How does the UK compare to other major economies?

英国与其他主要经济体相比如何?

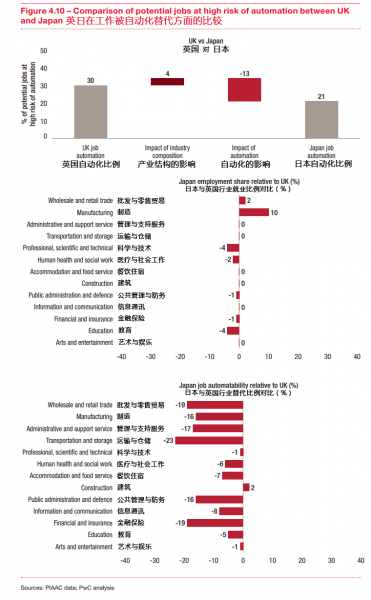

As shown in Figure 4.2 earlier in this article, we estimate that there is a greater potential impact of job automation in the US (38%) and Germany (35%) compared to the UK (30%), but a decreased potential impact in Japan (21%). As with the UK, the potential impact of job automation in other countries is driven by the industry composition of the country (i.e. the employment shares across sectors) and the relative proportion of jobs at high risk of automation in each of those sectors. However, a greater proportion of the variation between countries is explained by differences in the automatability of jobs within sectors.

如前图4.2所示,我们估计相比英国(30%),美国(38%)和德国(35%)就业受自动化替代的冲击更大,但是日本受冲击较小(21%)。同英国一样,其他国家受到的冲击大小取决于这个国家的产业结构(例如各行业就业数占比),以及该行业有高风险被自动化的岗位比例。但是,国家间中很大部分的不同被解释为不同国家同一行业内岗位被自动化可能性的不同。

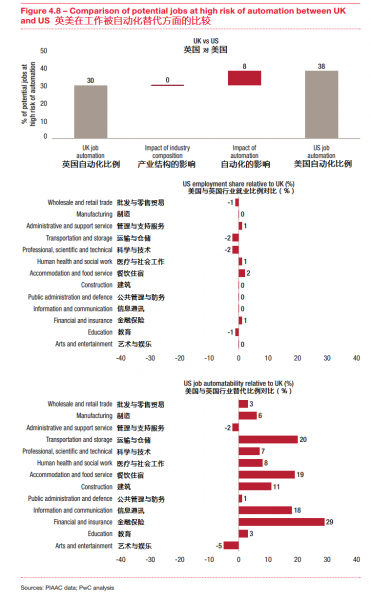

Why is the estimated risk of job automation higher in the US than the UK?

为什么美国的风险比英国大?

We find that the larger proportion of jobs at potential high risk of automation in the US is almost exclusively driven by differences in the automatability of jobs for given industry sectors. The US has a similarly service-dominated economy to the UK with relatively little difference in employment shares by industry sector (see middle panel of Figure 4.8). However, several important industry sectors show significantly higher potential job automation risks in the US than in the UK (see bottom panel in Figure 4.8).

我们发现,美国风险更大的几乎唯一的原因,是对象行业的被自动化可能性与英国不同。美国与英国有着类似的服务主导型经济,各行业就业比例相对来说差别很小(见图4.8中图)。但是,美国几个重要行业显示出显着高于英国的被自动化替代的风险(见图4.8下图)。

The most significant example here is the financial and insurance sector, where automatability is assessed to be much higher in the US (61%) than the UK (32%). Further analysis of the data suggests that the key difference is related to the average education levels of finance professionals being significantly higher in the UK than the US. This may reflect the greater weight in the UK of City of London finance professionals working in international markets, whereas in the US there is more focus on the domestic retail market and many more workers who do not need to have the same educational levels. The jobs of these US retail financial workers are assessed by our methodology as being significantly more routine – and so more automatable – then the average finance sector job in the UK, with its greater weight on international finance and investment banking.

这里最值得注意的例子是金融与保险,美国该行业岗位被自动化替代的比例被评估为高达61%,远远高于英国的32%。进一步分析数据显示,最关键的区别是英国金融专业人员的平均教育水平显着高于美国。英国伦敦的专业金融工作者们更多的是在为全球市场工作;与之相反美国则更关注国内零售市场,有更多的从业人员,却并不需要拥有与英国同行同样的教育水平。美国零售金融从业者的工作在我们的方法评估下,相比在国际金融和投资银行业务上有更大权重的英国金融行业工作,显然更多重复性例行工作的成分,也就更容易被自动化替代。

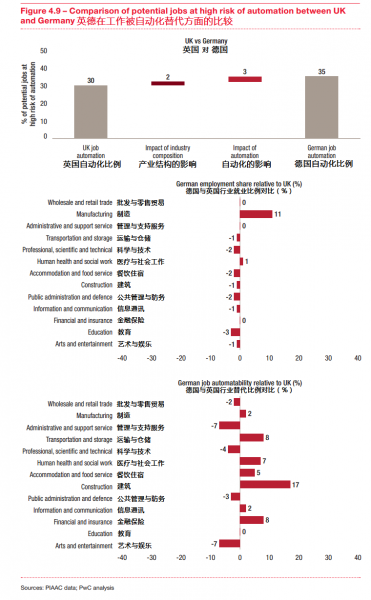

Why is the estimated risk of job automation higher in Germany than the UK?

为什么德国的风险比英国大?

In Germany, by contrast, the greater proportion of jobs at potential high risk of automation is driven by broadly similar sized impacts from both industry composition and job automatability by sector (see Figure 4.9). In particular, Germany has a higher share of employment in the manufacturing sector than the UK, and manufacturing has a relatively large proportion of jobs at high risk of automation. At the individual sector level, relative automatability levels are varied, but on average higher in Germany.

相比之下,德国有潜在高风险被自动化替代的岗位比例更高,则是来自于多种原因共同的作用,从产业结构到具体行业的自动化风险差别(见图4.9)。特别是,德国制造业就业比例明显高于英国,而制造业被替代的比例相对更高。就单个行业层面来说,自动化的比例各有不同,但是德国平均下来要更高些。

This is most marked for construction, where the proportion of jobs at high risk of automation is estimated at 41% in Germany but only 24% in the UK. The main difference is that for those working in building and related trades in Germany, 60% of all tasks are either manual or routine, while in the UK these account for only 48% of tasks. Instead there is a greater proportion of time spent on management tasks in the UK, such as planning and consulting others, and those that require social skills such as negotiating.

这尤其体现在建筑行业,德国的自动化替代比例在41%,而英国只有24%。主要区别在于,德国的建筑与相关贸易从业者有60%的工作属于手工作业以及重复性工作,而英国同业这一比例只有48%。在英国,有更多的工作时间用于管理类任务,比如设计和咨询等,这些需要社交技巧,比如商讨、谈判。

UK construction workers are therefore classified as being less automatable on average than their German counterparts. Any automation in the construction sector will require major advances in mobile robotics by the early 2030s if our estimates are to prove reliable. It is also unclear here, as in many other sectors, how far these kind of construction robots will work alongside human workers, complementing and enhancing their productivity, rather than replacing them totally. At the very least, there may be a long-lasting intermediate stage in the use of robots in construction and other sectors involving manual tasks outside tightly controlled factory or warehouse conditions.

这意味着,英国建筑从业人员被归为相比德国同行更难被自动化替代。如果我们的判断被证明是可靠的,在2030年代早期实现建筑行业自动化需要在移动机器人的研发方面有重大进展。同时我们也不清楚,如同其他一些行业一样,这些建筑机器人在多大程度上可以与人类工人共同工作,补充和增进他们的生产率,而不是彻底取代他们。至少,在机器人应用在建筑或者其他行业的过程中将会存在长期的中间阶段,在这个阶段在高度控制的工厂和仓库环境外还包含手工作业。

Why is the estimated risk of job automation lower in Japan than the UK?

为什么日本风险比英国小

In Japan there is a lower proportion of jobs at high risk of automation than the UK, despite having an industry composition that (like Germany) is more focused on manufacturing, which is one of the most automatable sectors. However, this industry mix effect is more than offset by the lower average automatability of most individual sectors in Japan relative to the UK, as shown in Figure 4.10.

虽然有着与德国类似的产业结构,专注于制造这个自动化风险很高的行业,日本有潜在高风险被自动化替代的岗位比例却比英国低。这种产业组合效应被日本大多数行业明显低于英国的被替代比例所大大抵消了,见图4.10。

One sector of particular interest because of its high total employment level is the wholesale and retail trade. In Japan, the proportion of jobs at high risk of automation in this sector is estimated at only around 25% as compared to around 44% in the UK.

一个非常有趣的行业,是就业人数庞大的批发与零售贸易。在日本,该行业被自动化替代的比例经评估只有25%,而英国是44%。

For retail sales workers, we found that the lower proportion of jobs at high risk of automation in Japan is partly due to a lower proportion of time conducting manual tasks compared with management tasks, such as planning or organising. Perhaps linked to this, sales workers in Japan are far more likely to need further training at work (60% compared with 10%) and a significantly higher proportion feel challenged at work (65% compared with 8%).

我们发现对于日本的零售销售工作者来说,被自动化替代比例低,部分源自其花更少时间进行手工作业而花更多时间进行管理类工作,比如计划和组织。有可能就是因此,日本的销售需要更多的职业培训(60%相对英国的10%),并且在工作中感受到挑战的比例更高(65%相对于英国的8%)。

Whether these projections hold true in the longer run depends on whether there are moves in Japan to change the nature of retailing, making it less labour-intensive on the US or UK model. This might involve customers doing more self-service in Japan than they do now, so reducing the need for skilled sales staff and increasing the need and scope for automation.

这些预测在长期来说能否保持正确,取决于日本是否采取行动来改变零售的特性,使得该行业不像美国或英国模式那样劳动密集。这可能包括日本的顾客比现在进行更多的自助购物,以减少对有技能的销售员工的需求,增进自动化的需求和范围。

G19:以下为原文注:

[1] This article was written by Richard Berriman, a machine learning specialist and senior consultant in PwC’s Data Analytics practice, and John Hawksworth, chief economist at PwC. Additional research assistance was provided by Christopher Kelly and Robyn Foyster.

注1:本文由机器学习专家、普华永道数据分析业务资深顾问理查德贝里曼,以及普华永道首席经济学家约翰霍克斯沃思撰写。克里斯多弗凯利和罗宾福伊斯特提供了研究方面的额外帮助。

[2] Martin Ford, The Rise of the Robots (Oneworld Publications, 2015) is one particularly influential example of an author setting out this argument in detail.

注2:马丁福特,机器人崛起(Oneworld出版社2015年)是一个特别有影响力的例子,作者详细阐述了这个问题。

[3] In both studies, this is defined as an estimated probability of 70% or more. For comparability, we adopt the same definition of ‘high risk’ in this article.

注3:在两个研究中,所谓高风险都被定义为70%以上的预计可能性。为了可比性,我们本文也采用同样的“高风险”定义。

[4] Haldane (2015) cites a Bank of England estimate of around this level for the UK based on their version of the FO analysis. This is also in line with other estimates by FO

themselves for the UK.

注4:霍尔丹(2015)引用了一份英格兰银行基于他们版本的FO分析所得出的英国的数值大约在该水平。同时FO自己对英国的一些预测中也提到了这一数值。

[5] For example, Autor (2015).

注5:比如,奥托(2015)。

[6] See Annex for technical details of the methodology used.

注6:所使用方法的技术细节详见附件。

[7] We also produced estimates for South Korea, but the results – both in aggregate and for particular industry sectors – were very similar to those for Japan, so we do not report them here for reason of space. AGZ also estimated very similar risks for Japan and South Korea, albeit with lower risk levels than our estimates due to the different methodology they applied to essentially the same data set.

注7:我们还做了南朝鲜的预测,但其结果——无论总体来说还是具体行业来看——都与日本的非常接近,所以限于篇幅我们没有在本文中详述。AGZ也预测日本与韩国的结果相近,虽然因为其对同样的数据组采用了不同方法导致风险水平低于我们。

版权声明

我们致力于传递世界各地老百姓最真实、最直接、最详尽的对中国的看法

【版权与免责声明】如发现内容存在版权问题,烦请提供相关信息发邮件,

我们将及时沟通与处理。本站内容除非来源注明五毛网,否则均为网友转载,涉及言论、版权与本站无关。

本文仅代表作者观点,不代表本站立场。

本文来自网络,如有侵权及时联系本网站。

图文文章RECOMMEND

热门文章HOT NEWS

-

1

最近,新冠肺炎疫情在日本有扩大的趋势,有专家呼吁日本应当举国行动起来,共...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

推荐文章HOT NEWS

-

1

最近,新冠肺炎疫情在日本有扩大的趋势,有专家呼吁日本应当举国行动起来,共...

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10